By Their Sickbeds

By Louland Escabusa, cicm

The author, from Pilar, Bohol, is a seminarian of the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (CICM). From 2011 until this year he was studying theology at CIFA - Communauté Internationale de Formation en Afrique (International Community for Formation in Africa). In September he is going to Hong Kong for a two- to three-year internship program.

Marina

Marina became a familiar scene. Every week there she was, seated on the bench just outside her room, often with her mother, a checkered shawl wrapped around her shoulders, her petite frame crowned with a contagious smile. The light in her eyes spoke of an enigmatic glee but couldn’t hide the pain and sorrow that almost gnawed away at her hope, her joy, and the very purpose of her being. Among the faces of patients that I encountered during my apostolate in the hospital hers was one of the few that left an indelible mark on me, making my apostolate meaningful and my integration in Cameroon enriching.

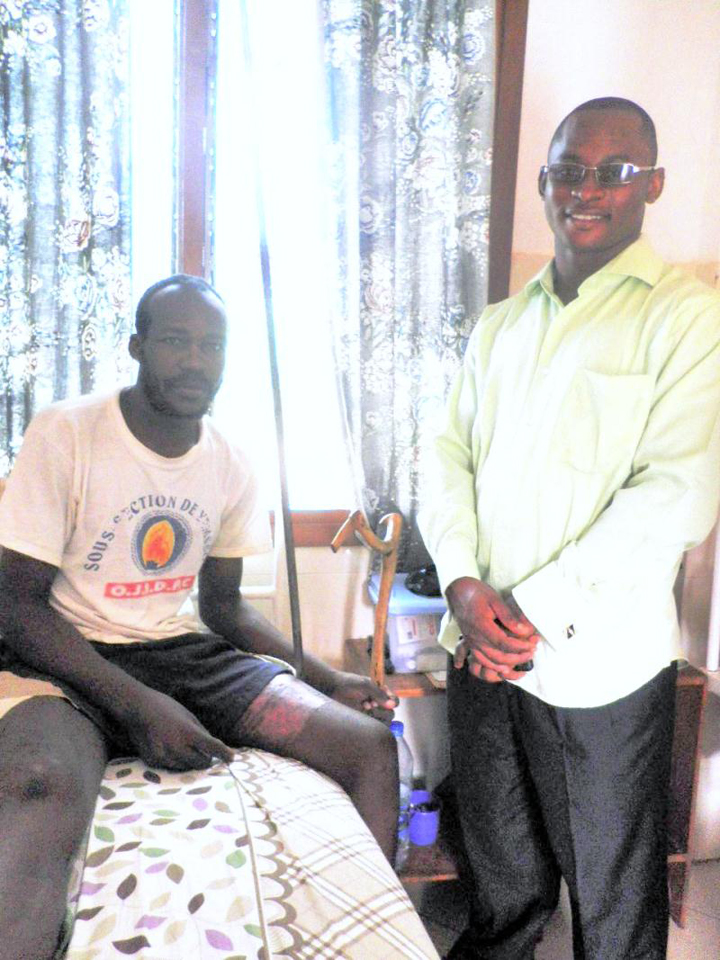

Emmanuel Mandona CICM visiting a patient

In our community of initial formation Saturday afternoons and Sundays are devoted to the Apostolate, one of the four pillars of our formation, Spiritual, Academic and Community Life, the others. I worked with two confreres, Amos Onezaire, a Haitian, and Emmanuel Mandona, a Congolese, at the Centre Hospitalier Dominicain de Saint Martin de Porres, located on a hilly periphery of Yaoundé, the capital, run by Dominican Sisters. The unpaved road leading to the hospital was a weekly challenge, with its literal highs and lows of humps and holes. If rainy we had to struggle through mud, if sunny through dust.

Our Lady of Victories Cathedral, Yaoundé [Wikipedia]

Our main work was visiting the patients. It helped that the three of us were of different nationalities and I blanc, white, as Cameroonians refer to non-blacks, because that was an easy starting point in conversation to put one another at ease. I usually approached the guardians or ‘watchers’ of the patients, who were usually in the corridor. Almost always, the conversation would start with a friendly ‘Salaam’ followed by a ‘Q & A’. I would ask what had brought them there and they would ask what a blanc was doing in the hospital. The conversation would then lead to topics as mundane as the weather, or to an assessment of the more than 30-year reign of President Paul Biya.

There were usually three to five patients in each room. The observation room, maternity ward and pediatrics section had room for more. The children in the latter had common sicknesses such as malaria and typhoid fever and, to my surprise, there were cases of hernia, common in Cameroon among adults and children.

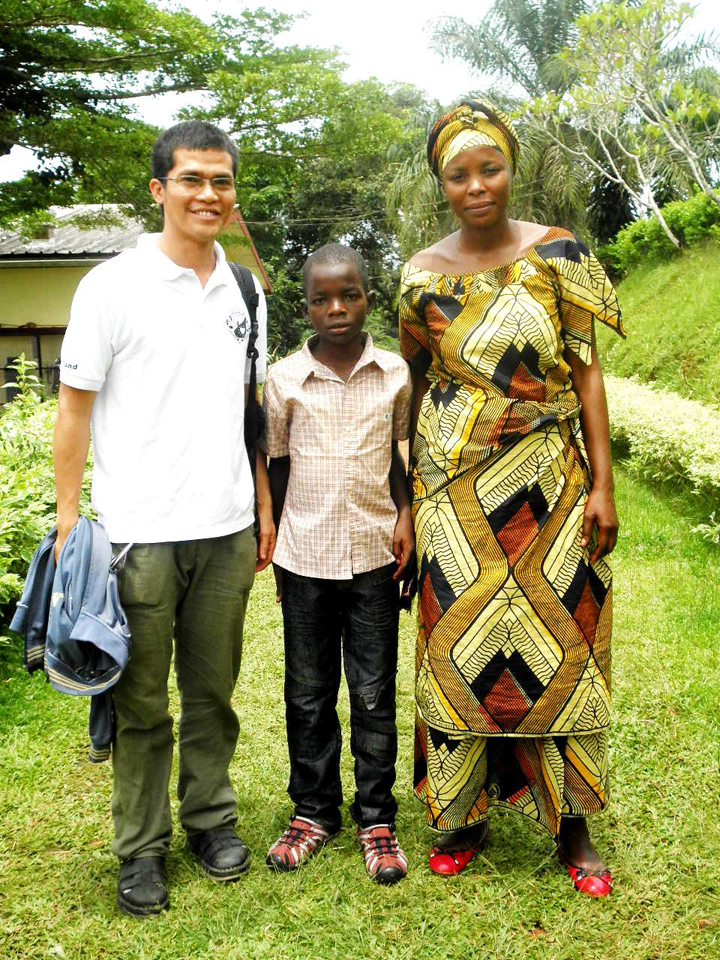

Louland with a patient

I learned from Marina, when we started our apostolate, that she had already been confined for more than a month. She had undergone an unsuccessful cesarean operation. The child was a girl. Marina had also lost her first child. The wound from the operation was already healing and Marina was hoping to be discharged soon and could have been an out-patient while continuing her medication. But she didn’t have the means to pay for her hospitalization. I was humbled by her openness. The father of her child had gone away after learning that Marina was pregnant and had made no contact since. Her widowed mother had traveled from their village a hundred kilometers away to watch over her. She had a sister Yaoundé who, from her limited means, brought them food time and again. When things were really tight, Marina and her mother relied on the mercy of other patients and guardians.

In one of our conversations Marina sobbed over the fact that she wasn’t even able to attend her daughter’s burial. Her grief was ‘suspended’ under one concern after another. She felt guilty over the loss of two children already, claiming that she must have sinned so much that her womb had become inhabitable for the innocent. And if the death of her child wasn’t agonizing enough, she felt abandoned by some relatives who refused to answer her calls. She needed help to pay the hospital bills which were beyond her capacity. ‘Had I died, all of them would have gathered before my dead body and contribute something for my burial. Why can’t they do that now while I am still alive and when I need it most?’

I truly felt for her and my inability to respond to her concrete needs made me feel very limited and my apostolate inadequate. Yet, we could only do as much. But at least we could let her feel she wasn’t abandoned.

Louland with a hospital worker and her son

Apart from a few patients like Marina who needed an extended period of treatment, each week I met new faces. This demanded a certain ‘audacity’ and a willingness to undergo a process from being strangers to companions, repeated every week. At times I was hesitant and still struggled with French. It would have been easier for me to coil up in a corner. Besides, there were times when patients even questioned my intentions. There were times when I felt that my presence or absence didn’t really matter to patients.

However, the great majority, like Marina, were welcoming. That was enough to motivate me. Like her, some patients were very open about their condition and the struggles they were going through. They could be very personal at times. I felt I wasn’t the right person for them to confide in. We usually shared the Sunday gospel with them invited them to pray with us. Some stormed us with questions about life in the seminary, or about daily life in the Philippines. In turn, they often described their life in the village where they were from or the circumstances that led them to hospital. This exchange was very enriching for me.

Mourning dance of Cameroonian women

The poignant events I witnessed spoke of the similarities and differences in the way we respond to events. It could be as universal as the unspeakable pride and joy of a first-time father, his daughter asleep in his arms. It could be as particular as Cameroonian women expressing their grief through dancing when a family member dies. It could be as specific as Onana, an amputee who rushed to the hospital upon learning that his brother had collapsed and taken there. It turned out to be simply a case of drinking too much beer after a football match!

I came to realize that I wasn’t visiting the hospital just to accompany the patients for they might have had little need of that. It was a companionship that some of them and I were building, an encounter of persons enriching one another. They helped me slowly uncover the wonders - and blunders - in the life of a young missionary in a foreign land. They showed me the reality of joy, sorrow and pain in a different context. Together we explored the intricacy of human relation in a milieu that, at first, I wasn’t familiar with. We weaved together our stories, the threads that made a beautiful tapestry of human existence. For all of this I can only be grateful.

A Pygmy couple at the hospital

As for Marina, I got used to seeing her sitting on a bench outside her room, often with her mother. But halfway through the third month of our apostolate she was discharged. I was just glad that, finally, she was out and, I hope, back to the normal rhythm of her life. That was how it was supposed to be. In our apostolate we didn’t say such things as, ‘Hope to see you next week,’ nor, ‘Until next time,’ nor anything suggestive of a longer stay in the hospital. We would only wish the patients well. We could only assure them of our prayers.

The stories of Marina and some of the others now play like a slideshow in my mind. I can only pray for them and wish them well. And I ardently hope that our encounters were as enriching for them as they were for me.

Pope Benedict’s visit to Cameroon 17-20 March 2009

Cameroon

National Flag [Wikipedia]

This Central African country covers an area of 475,442 square kilometers (Philippines: 300,000) and in 2013 had an estimated population of around 23,000,000 (Philippines 101,000,000). 40% of its people are Catholic, 30% Protestant and 18% Muslim (Philippines: 80.1 percent Catholic, 5.8% other Christian groups, 5-11% Muslim). Cameroon’s official languages are French and English, though it has 230 indigenous languages. The Deaf there use American Sign Language. The country’s major sport is football (soccer) and its national team has been one of the most successful of African countries in international competitions.

Our Lady Queen of Apostles is the Patroness of Cameroon.

Basilica of Our Lady Queen of Apostles, Yaoundé [Wikipedia]

St John Paul II visited Cameroon 14-16 September 1995