Sabbatical for Future Commitment

By John B. Din

The author is from San Miguel, Zamboanga del Sur. In 1993 he went as a Columban Lay Missionary to Brazil where he spent seven years before being assigned to Peru. In 2011 he was appointed Coordinator of the Columban Lay Missionaries in the Philippines. Last year, after his sabbatical year, he was appointed Regional JPIC (Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation) Coordinator and is based in Quezon City.

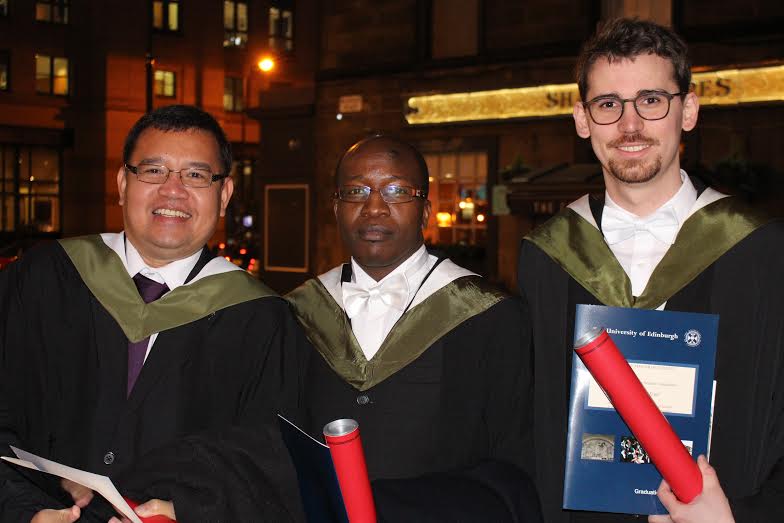

John Din (left) and friends at graduation, University of Edinburgh 2015

In his book The Light Which Deems the Stars the late Columban Fr Colm McKeating, who worked in the Philippines for many years, argues that the sabbatical is the climax of creation and includes the care and protection of every creature because they all belong to God. Thus a sabbatical year is a not about rest and idleness but is rather meant to be an active and intense experience of God who is the ground of our existence. Indeed, it is about breaking with routine and the familiar and uncovering the extraordinary behind the veil of everyday experience. It is amazing how a different kind of work can reinvigorate when it fits the desire of the spirit.

After more than twenty years of being a Columban Lay Missionary, I spent my sabbatical studying for a Master’s degree in Science and Religion at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, the sixth oldest university in the English-speaking world. I had planned to start with a Thirty-day Retreat (The Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola).

Unfortunately, due to a problem getting a visa, I had to forego the retreat and start my formal studies directly.

John Din at mission-sending of Luda Egbalic and Jenanydel Nola, now in Korea, 2014

I tried to combine reflection on my own experience with the demands of study. I wrote essays about suffering and evil, drawing from my experience in dealing with schizophrenia in the family as well as science and indigenous wisdom relating to the struggle of the Subanen people in Midsalip, Zamboanga del Sur, against extractive industries. It was my way of pulling together the experiential and the theoretical and discovering how they enrich each other. It was a form of self-confrontation, questioning my assumptions, beliefs and hopes.

I decided to study science and religion because I felt the need to have a good grasp of science after seeing through my engagement with different groups, NGOs and civil society, how it has strengthened the argument about climate change. In this age where facts and proofs determine the validity of an argument science can challenge us by questioning our assumptions and presumptions.

Science has shown us the evolutionary nature of the development of our universe since 13.7 billion years ago. It shows the dynamic and continuous creativity present in creation. Contrary to the perceived conflict narrative of science and religion, which is an invention of the nineteenth century, history provide a dynamic relation between science and religion. For example, the long-held belief of indigenous peoples around the world that everything is interconnected is affirmed by both evolution and quantum theories. Both affirm the dynamism and uncertainty in reality. Thus, our deeper understanding of the changing face of God our Creator as we reflect on our life experiences over the years is a healthy indicator that we are indeed relating to a living God.

Three Columban half-marathon runners, Peru 2011: Fr Bernie Lane (Australia), John Din, Fr Tony Coney (Ireland)

I felt I was plunged into hard science since I had to explore and deal with two particular persons who were both religious and scientists. My dissertation discussed how science and mysticism inform each other, focusing on the lives of Fr Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881-1955) and Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882-1944), a Quaker. In exploring the life of Teilhard I had to research his views and grapple with evolution. With Eddington, I had to deal with his general relativity and quantum theory. I found myself struggling to grasp three major breakthroughs in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

While writing my dissertation my desire for the Thirty-day Retreat was reawakened, after reading the life of Teilhard. The Spiritual Exercises helped him deal with the apparent contradiction of loving God and loving the world. There is a big difference between studying the Spiritual Exercises and doing the retreat itself. Having now been through the Exercises, I can understand better the struggle of Teilhard and how he came to his own synthesis of the apparent contradiction. Later I realized how my study led me back to the Thirty-day Retreat. This is my experience of how the study of science leads one to the Divine.

Gratitude was the dominant feeling during the retreat: gratefulness for God’s faithfulness through the many people I met in Brazil, Peru and the Philippines; many are unknown to me and known only to God.

John Din with staff of the Happy Earthworm Ecology Project, Peru

Now I am back in the Philippines and have been appointed Regional JPIC Coordinator. I am looking forward to the fruits of my sabbatical study and life experience in Brazil, Peru and the Philippines as a Columban Lay Missionary. The door is open for surprises, an attitude proper to a reality that is dynamic and infused with the divine. One of the pleasant surprises is Laudato Si’, the encyclical letter of Pope Francis ‘On care for our common home’, because it calls for a deeper understanding of who we are in the light of recent contributions from science and the current ecological crisis that we are facing. I am very grateful to the Columbans, priests and lay missionaries, as well as benefactors for this opportunity to get away from the routine and engage in an active resting.