Healing The Sins Of Evangelization

By Fr Chris Saenz SSC

Father Saenz, a Columban from Omaha, Nebraska, USA, was ordained in 2000. He had part of his formation in the Philippines.We are now observing the Year of the Eucharist. His article shows how a debate over the role of the Eucharist helps heal wounds caused by ‘the sword and the cross’ in Chile and Argentina.

Ever since childhood I was always taught that the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, were the cornerstone of our Catholic faith. During my training as a priest, it was reinforced that the Eucharist is the center of our faith, the most sacred Catholic celebration. Jesus Christ’s body, broken and shared, brings healing to his people.

The confession of sins and their absolution by a priest is a sign of this healing. Furthermore, the priest, before receiving the body and blood of Christ, must recognize his own weakness and offer it up to God as a sign of the wounded healer. The Eucharist gives such power to heal that those who are denied it feel the pain of not partaking in this most-valued sacrament.

But what if the Eucharist can be a symbol of imposition and oppression for a people? What if the celebration of the Eucharist opens old wounds instead of healing them? I face these powerful questions as a missionary priest, and they challenge my core beliefs.

Working with ‘The People of the Earth’

Since March 2001 I’ve been working with the Mapuches, the indigenous people of Chile. The word mapuche means ‘people of the Earth.’ I work in southern Chile particularly with the Mapuche tribe known as lafkenche, ‘people of the coast’. Certainly, the native people’s pain caused by evangelization through the ‘sword and the cross’ and their cry for justice are much older wounds than the misery caused by the military dictatorships of the past century.

But here in the Chilean region of Araucanía, those evangelization efforts, which happened just over 100 years ago, are still fresh in the minds of people. Some Mapuches still can remember denying their culture and accepting Christianity in order to survive. For a Christian missionary, it can be uncomfortable supporting a people to whom we owe an historical debt.

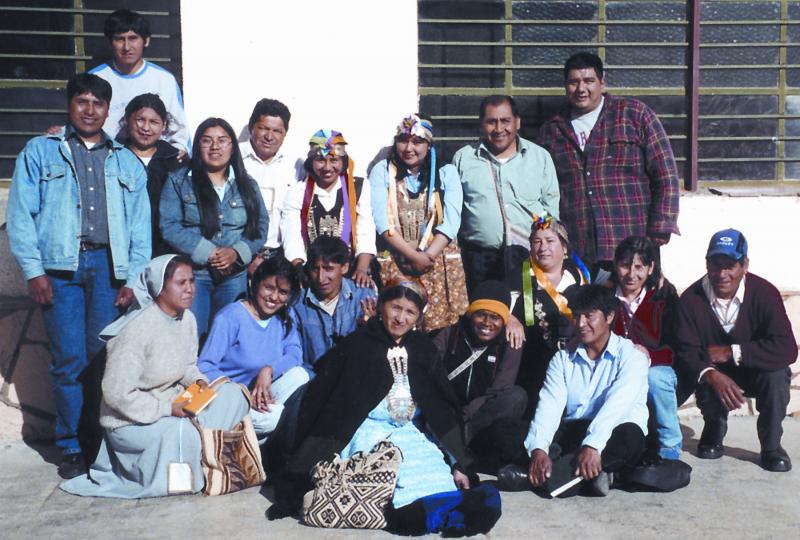

Recently, I’ve worked with the Diocesan Commission of Indigenous Ministry, which is comprised of Mapuche and non-Mapuche pastoral agents (priests, deacons, religious and laity) interested in dialogue and preservation of the Mapuche culture. I was invited to an organizational meeting for the annual seminar on the Mapuche religion to be held in Argentina in November 2004. Our commission and two other ministries – one each from Chile and Argentina – offer support to the Mapuches from Argentina and Chile who organize the seminar.

Non-Mapuches attending the four-day seminar are pastoral agents who work with the Mapuches to reinforce their endangered culture by preserving the Mapuche’s traditional language, religiosity, education, medicine, sports and social structures.

The meeting is an excellent opportunity for younger Mapuches to listen and learn about their culture from elders. For non-Mapuches, it is an opportunity to listen and observe. Even though most Mapuches attending are Catholics, the Eucharist is not celebrated during the seminar.

Sacraments as subjugation

This fact came up during the organizational meeting. When the Mapuches involved presented the proposed program to Bishop Marcelino Palentini SCI of Jujuy, Argentina, near the Chilean border, he asked, ‘Why can’t the Eucharist be included in the seminar?’ The bishop had attended the seminar for years, but never said a word about the lack of a Eucharistic celebration. He often left the seminar to celebrate the Eucharist in private, but he thought this was celebrating the Eucharist secretly. ‘Why should the Eucharist be celebrated secretly when it is the center of our faith?’ he asked.

Silence came over the room. A Mapuche woman eventually spoke. She told the bishop that many Mapuches attending would look upon a Eucharistic celebration as the Church trying to manipulate the seminar and enforce its sacraments, like it had done in Chile’s history. Another Mapuche said the seminar was a place to celebrate their spirituality and that their rogativas (prayer sessions) held each morning were just as sacred as the Eucharist. Another said non-Catholics might be offended by the sacrament.

The bishop listened to their concerns, but insisted that the Eucharist is essential and can be used as a point of dialogue.

Other Mapuches spoke up. They said that although Bishop Palentini had been more open and accepting of them, many of their experiences with bishops and priests had been negative. Many, they said, don’t ask for dialogue or show a willingness to learn their culture. Eventually, a non-Mapuche priest said it was not the Catholics’ place to include the Eucharist in the program; the Mapuches must decide.

When the bishop heard this, he was very apologetic. He asked for forgiveness for any hurt feelings he might have caused. The people accepted the apology and stated that the conversation was fruitful, because the bishop gave the Mapuches the time and the confidence to express their feelings.

A Mapuche coordinator then said, ‘Maybe it’s time to heal this old wound.’ He suggested that free time could be worked into the program so that those attending would have a couple of hours to do as they pleased. Even though there would be no mention of Eucharist or sacraments, those who were Catholics could freely celebrate the Eucharist. This time would allow others of different religions to celebrate their faiths as well. All agreed to this suggestion.

Time to listen

As a Catholic missionary priest, I’m often invited to question my beliefs in the light of another culture and its history. This can be uncomfortable. The Eucharist is a fundamental tenet of our faith, but I know it can be a source of pain for others. Listening to stories about this pain can heal these wounds.

When the Mapuches talk about the pain of Christianity in their history, it is not a time to walk out. It’s a time to be quiet and listen. Only in this way can this old wound begin to heal.