In Prison in Peru

by Fr Noel Kerins

Columban Fr Noel Kerins was ordained in Ireland in December 1965 and has spent most of his priestly life in Peru.

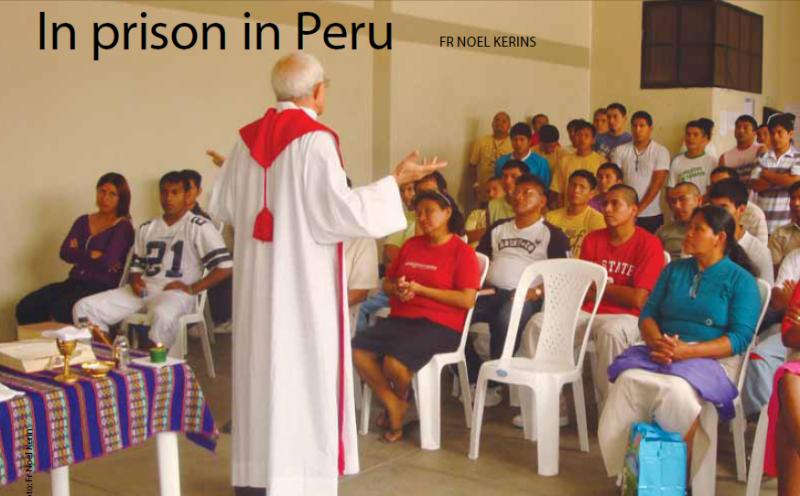

Columban Fr Noel Kerins and his prison team at a Mass for prisoners.

It was a hot and humid day. The jail is isolated and surrounded by sand. The prisoner's name was Peter; he was 22-years-old. I asked him his name, but he looked at the ground. His face was sad. He had just been baptized; his mother and sister had arrived for the ceremony. I had embarrassed him by asking for his father's name.

In Peru, I would be called Noel Kerins Fitzgerald: both my father's and my mother's surnames are included. When Peter responded ‘My father never recognized me’ he suffered a double loss of face. He had only one surname, and now he had lost his honor, admitting that he was illegitimate, and that in front of a foreign priest.

Perhaps to some this episode might appear trivial. Eight years as a prison chaplain in Lima has taught me otherwise. The vast majority of those in that prison - in all 3,600 - are victims before they victimize others.

In Peter's case, his single mother was the bread-earner of his home. She worked a 12-hour day for the equivalent of US$10 dollars a day. His sisters, one five years older than he, the other three, looked after and nourished him from the outset.

Need I say more? Attempt to walk in those shoes for 22 years: I honestly believe I would have fared much worse than Peter. There are 57,529 prisoners in Peru's 66 jails. Two-thirds of them have not received a sentence.

On being accused they are jailed ‘as a precautionary measure’. In practice this means that a prisoner can be four, five or six years in jail, while being innocent. One of the tasks that we do is to try and locate a piece of paper (called ‘expediente’) so that legal proceedings may begin. This is a tedious and painstaking task that requires time, dedication and endless patience.

On being accused they are jailed ‘as a precautionary measure’. In practice this means that a prisoner can be four, five or six years in jail, while being innocent. One of the tasks that we do is to try and locate a piece of paper (called ‘expediente’) so that legal proceedings may begin. This is a tedious and painstaking task that requires time, dedication and endless patience.

If the prisoner is not from Lima it also requires travel. Even having found it, legal proceedings are painfully slow. At each step payment is required. The partner is generally poor and trying to look after two or three children.

Over half the total prison population is imprisoned in Lima and overcrowding is the norm. The population capacity of Peru’s jails is 28,689: the total prison population is twice that figure. Corruption is endemic in the system. From the smallest detail, eg, where a bed is placed, to the severity and extent of the sentence, everything is influenced by who I know and how much I am prepared to pay. One prisoner put it very succinctly to me one day as we spoke, ‘With $10,000 I could be out of here within two weeks’.

A prison ombudsman (‘fiscal’) certified after due process that the food served in the jail we visit is not fit for human consumption. To move on that fact - verified by the competent authority - would require, perhaps, three years. It would certainly require more political will than exists at present.

In fact family members nourish the prisoners. Hundreds of kilos of food are brought to the prison on each visiting day. In the two jails that we visit there are 3,600 prisoners, 500 or them women.

In fact family members nourish the prisoners. Hundreds of kilos of food are brought to the prison on each visiting day. In the two jails that we visit there are 3,600 prisoners, 500 or them women.

In both jails there is, technically, a small office for health care. It exists but, in practice, it is purely nominal. By way of illustration, I had two operations for a particular health problem during the last four years.

I received the best of care. With all that I was still recuperating with medication for the best part of six weeks. In the prison I came across one prisoner who suffers from the same condition. He receives not as much as an aspirin!

The paper work (‘tramites’) to actually get the medical team to the jail would take at least a year and a day. The same goes for tuberculosis, AIDS, or any other condition. So, the picture is indeed bleak.

What then can we do? Well we are a group of 33 members who pledge to visit the jail, in pairs, on one morning or afternoon each week. We offer a human face within an inhuman system. We chat about normal life happenings, a birthday, a visit from a friend, a death in the family.

We share a reflection on the words and the actions of Jesus for those who wish it. We assist the poorest prisoners to locate the above-mentioned expediente, so important since two-thirds are jailed without a sentence.

We celebrate the Eucharist on important occasions, Holy Week, Christmas, on significant feasts, or on the death of a relative. We facilitate education programs, recognized by the Government, so that some may be motivated to continue their basic primary and secondary education. With the help of a professional medical team, we do a screening for tuberculosis and AIDS once every year.

In the Gospels, we don't read that Jesus visited a jail in his homeland, but he did remind us that one of the tests we will face before the final curtain falls will be, ‘I was sick and imprisoned and did you visit me?’