July-August 2003

A Late Life

By Joy Amiloquio

I belong to the Teresian Association (Institución Teresiana), an international Catholic lay association present in 30 countries. Our founder was a Spanish secular priest, Pedro Poveda, martyred in 1936 and beatified on October 10, 1993. I was only 16, in first year at the university, when I came to know the group, 18 when I was formally accepted, and 22 when I came to Taiwan, home for me now. I see an irony in having been sent as a missionary at an early age while my work involves a late life. Father Poveda wrote ‘Your mission is to season the tasteless wherever you go, in the place where you live, among the people you meet.’ I try to be salt and give flavor to the context where I am and that is being with students at an unusual time – a late life. Poveda went on, ‘It is good deeds that witness for us and speak with incomparable eloquence of what we are.’ I try to be a witness by my good deeds in the university, by ‘wasting’ quality time, even late at night – a late life. How would I know the hunger for God in others if I wasn’t around to listen to their questions?

It’s sort of late to be arriving home every weekday evening at 11:30. It’s sort of strange to be with students on a pleasant Sunday afternoon when you’re supposed to take your weekend rest, stranger still when you’re in school on Sunday nights. Why am I out of the house on weekends, spending time with students with it isn’t a school day?

The arrival of a late-evening visitor to my office today may explain. I work atJung-Jiao Fu-Dao Jung-Shin, which translates as the Religious Guidance Center of Fu-Jen Catholic University, in Taiwan. The last time I saw him was two years previously when he was an evening student in the History Department where I was a counselor. Instead of making an appointment, he came looking for me when I was in the middle of an activity with students. But he had something urgent to tell me: he was questioning the existence of God. He was neither Christian nor Buddhist – he had no religion. But he had a vivid memory of joining a church Christmas choir. He liked the experience and told me, ‘I have kept a space for God in my heart from that moment on.’ He was afraid the space was getting smaller with the hundreds of philosophy and science books he had read. But he still wanted to believe that ‘God’ exists. My listening to him helped him to continue his search for God.

Spending time with the young

Am I really fulfilling the mission of being a co-worker of Christ in sowing the seeds for the Reign of God here in Taiwan? I come home late because I ‘waste time’ with students during their free time, which on weekdays means after 5:30. I listen to their stories and eat with them. On weekends they do volunteer work in the leper center and I go with them. The young Catholics have Mass on Sunday night and I spend time with them.

On weekends I normally go to work after lunch. I facilitate small life/faith-sharing groups to which I give names such as ‘Circle of Love,’ ‘Soul Station,’ ‘Ripples.’ I also have Bible-study encounters. I invite individual students for a friendly chat. We usually establish a certain trust and most come again for a deeper level of sharing. When students aren’t around, I prepare materials, attend meetings, and find space to regain the energy lost during the week.

Catholics are a minority in the university and campus ministry is for me making a difference in the lives of others, students and colleagues, by my Christian witnessing, to be salt and light in this particular context. Being a religious guidance counselor is sowing seeds, the fruit of which I may not reap. In my short talks with students doing volunteer work in the different centers, I always mention that love is being made alive by them, the love that Christ taught us. I think students feel my love and concern when I chat with them. I always assure them of my prayers whether they’re Christian or not. I tell them that prayer is an important element of my faith and a source of strength. Many times students, meeting me casually or dropping by the center, must ask that I pray for them.

‘We must give, not ask…We are to take advantage of every opportunity, every fitting moment. We must be even-tempered and persevering in the midst of all kinds of upheavals, internal and external, our own and those of others. We must temper justice with mercy; we must know when to speak and when to be silent. We must set our hearts on what is spiritual, but without failing to put our hands to the material task. We must teach by working and suffering’ -- further words of Blessed Pedro Poveda that motivate me. I try taking advantage of every opportunity, every fitting moment, to nourish my body and spirit. I wake up late in the morning, at about 8:00, when everyone is reporting for work – a late life! I rest on Monday mornings and relax on Friday afternoons, strange as it may seem, but I’m happy to live this kind of life as a missionary. It’s a choice in the first place!

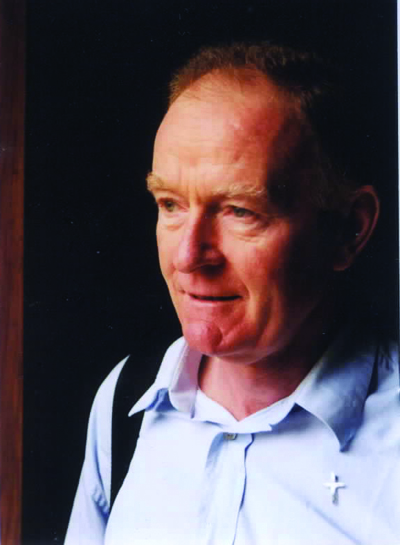

A Poem By Fr Rufus

Columban Father Rufus Halley was shot dead in Lanao del Sur on 28 August 2001.

On 19 February this year the Aurora Aragon Peace Foundation and Concerned Women of the Philippines posthumously gave Father Rufus the Aurora Aragon Peace Award ‘for Peace Advocacy and Peace Making.’

The dawn has broken through

The fears and snares of darkness

Are shattered, scattered, put to rout

Hold your head up high, oh man,

And taste the sweetness of morn.

Behold, she’ll rise far to the East

Strong and gentle in silence.

Rejoice, oh man, your freedom’s nigh

The wiles, the winter, snares and shackles are no more

My God, my God, how great you are

For He has set me free.

The lush and fragrant misty dawn

Bejewelled awaits her rising sun

Whilst the morning star retires in silence

Without fanfare, her job well done

And Mother Earth enfolds us all

And bids us drink from her abundant breasts

The nectar of new life in deed

And to proclaim – He is great indeed

For He has set me free.

And I race up to the hill

And shout to far and near

To wise and prudent, strong, secure and gentle, too

He is great and He is near

And He has set me free.

Full and overflowing and bursting forth enraptured free

My heart takes flight and soars upon the heights

No eyes to sight except on high

And far below its beauties are

But just a pale reflection of His presence sure

Ever far yet ever near

Beckoning to me, on and on

He is great and now I’m free.

A Pop Star Catholic Priest

An edited version of an article that first appeared in LADOC, Peru

With his front line role in taking religion to the masses in Brazil through the electronic media, Father Marcelo Rossi has been at the center of more than one storm in recent years. While he denies being a ‘pop star’, it is difficult to see him any other way. Newspapers describe him as ‘young, handsome and athletic, selling millions of records, with TV stations vying for his presence.’

With his front line role in taking religion to the masses in Brazil through the electronic media, Father Marcelo Rossi has been at the center of more than one storm in recent years. While he denies being a ‘pop star’, it is difficult to see him any other way. Newspapers describe him as ‘young, handsome and athletic, selling millions of records, with TV stations vying for his presence.’

I never took a communication course and don’t want to create a model (of mass communication). All I want is for the Church I love to grow more each day,’ says the 34-year–old priest, who is based in Santo Amaro Diocese in Sāo Paulo, Brazil’s largest city. More than 80 percent of Brazil’s 160 million people are Catholic. According to Fr Marcelo, as the priest is popularly known, about four percent of all Catholics took part in the charismatic movement in 1997, a figure that quickly grew to 12 percent. He thought it ‘could reach 40 percent’ soon.

Celebrity priest

More than 30,000 people attend Rossi’s Masses in a Sāo Paulo neighborhood, and in just a few weeks his compact disc, Music for Praising the Lord, sold more than 3 million copies, a mark never before reached by artists signed by PolyGram, Rossi’s recording label. His daily program on Radio America, with more than 60 stations, has an audience of 800,000. The Brazilian TV networks, Globo, SBT, Bandeirantes, and CNT, vie for his presence because ratings go up when he appears.

Less political sermons

Rossi is a true phenomenon inside the Brazilian Catholic Church as well. Shunning the more political tradition of Brazil’s clergy, he never addresses social issues in his homilies. He considers homosexuality a sin and condemns abortion, contraceptives and sex outside marriage. ‘The work of priests and religious must be more spiritual than social,’ he says.

Business and evangelization

According to newspaper reports, Rossi owns a company called Byzantine Rosary Ltd, which sells various products at his well-attended liturgies. Although the company is in the names of Rossi and his mother, Bishop Fernando Figueirido of Santo Amaro Diocese has said it is in the service of the church’s social mission in Sāo Paulo. Antonio Kater, author of the book Marketing in the Catholic Church, says, ‘The Santo Amaro Diocese seems like a business. It is well organized and knows how to sell its product: salvation.’

Commercial religion

The apparent close ties between Rossi and Figueirido are reflected in their public statements. The bishop has defended Rossi when the priest has been the subject of debate in the Brazilian Conference of Bishops, and Rossi has said he always consults Figueirido. Theologian Leonardo Boff has been especially critical of Rossi, calling his style ‘commercial religion’. ‘Father Marcelo is happy believing God is in heaven, without realizing that people don’t have bread,’ says Boff, author of 40 books on theology and the Church.

After Pope’s Visit

‘When Pope John Paul II was in Brazil in 1997 and he asked us to think about new ways of spreading religion, I thought the Church needed to take advantage of the media,’ says Rossi. Within two years of the papal visit Rossi’s ministry had grown rapidly from its humble start as a weekly program on a radio station outside Sāo Paulo.

Fit for Leaps

‘Until I was 10, I dreamed of driving a Formula One race car. Then I thought I could become a good soccer player. But the death of a teenage cousin brought me to church and put me on the path of the Lord,’ says Rossi, whose background in physical education was good training for the leaps and gestures that characterize his Masses, which are all accompanied by music.

Too famous to go out

The priest’s life has changed so drastically in such a short time that he needs security guards whenever he appears in public. When he goes to a Mass, he uses three vehicles to throw his followers off track. Since becoming famous, he has tried only once – without success – to go to the corner bakery to buy bread.

Headliner

Rossi has made headlines for various reasons. The national police recently took action to shut down a web page that included offensive remarks about him, and Sāo Paulo officials closed his ‘church’, which is really part of an old factory, for safety reasons.

The city’s Building Department calculated that he would need at least three weeks to make repairs and meet requirements, but the work was done in record time. One hundred parishioners pitched in and the church reopened in less than a week. According to the weekly newspaper Epoca, about 900 volunteers assist the popular priest in various ways.

Rossi has been the target of criticism by evangelicals. The Christian magazine Vinde reported that he had appropriated evangelical songs without the composers’ permission. Although PolyGram worked out arrangements with them, the claims added fuel to accusations by Edir Macedo, leader of Brazil’s huge evangelical Universal Church, that Rossi ‘clones evangelical services and uses clichés that sound religious.’

Far Away

By Eric and Margaret Young

It is difficult for parents to let go of their children. Here, Eric and Margaret share with us how they cope with their daughter’s absence. Sarah left England and came to the Philippines as a missionary. In her article, ‘Happy where I am’, she shares with us her life away from home.

It is difficult for parents to let go of their children. Here, Eric and Margaret share with us how they cope with their daughter’s absence. Sarah left England and came to the Philippines as a missionary. In her article, ‘Happy where I am’, she shares with us her life away from home.

Phone bills are suddenly much larger. Kitchen scales, which have done good service for years, are repaired because accuracy is suddenly essential for the cost of the parcels. Why? Because our ‘child’ is thousands of miles away, and it is vital to keep in touch. This is the age of adventure, freedom, cheap travel. Youngsters take gap years between high school and university, leave home with a backpack and head off into the wide blue yonder. Anxious parents meet and swap notes and worry about their absent offspring. Parents in the United Kingdom have come to terms with the fact that they won’t see their young until the gap year is run.

Journey into the unknown

As parents of Sarah, a Columban lay missionary in the Philippines, we are part of this club, but with a difference. We know that our daughter has left home, not for 12 months’ adventure, not for the excitement of seeing the world or traveling as far as possible in the time allotted before settling down to university or work. She has left us to live a life that has called her to give up her job as a teacher, her home, her friends and commit herself to three years in a foreign country. She has asked the Columbans to show her the way to travel into a world very different from that which she has always known. I doubt if she and her companions know where the journey will eventually lead them. But this is not the most important part. Even if after all their wanderings they return right back to where they set out from they’ll have traveled on a journey in which they’ll have found themselves.

Parents left behind to wonder why and worry are also on a journey. We ask ourselves questions and not just the mundane ones about Sarah’s health and strength. We who have nursed her through all her ailments suddenly find ourselves reading up on tropical diseases. When we get the phone call and are filled with dread when asked whether we want the good news or the bad first – the good news being ‘I’m out of the hospital now,’ the bad ‘it was dengue fever’ – we want to shout down the line, ‘Come home now’ but don’t. We just say, ‘Thank God.’

Nothing else but prayers

We sit alone in our pleasant solitude and think of Sarah feeling isolated from the life she has left, wondering how she can bear the loneliness which must be inevitable, the weather, the food and the customs, ‘Please God, giver her strength and fortitude.’

We scan the newspapers daily and listen to the radio for details of happenings in the Philippines. When something does occur we’re told when we next contact Sarah, ‘That was 1,000 miles away.’ But we check the atlas and pray, ‘Dear Lord, save her from harm.’

We receive Sarah’s letters and read between the lines. The words on the page tell the everyday stories of her life but the form of sentence, the slant of the pen, the actual choice of the words we are reading tells us much more. We say, ‘Please God, be near her.’

We get photos and pore over them. ‘She’s getting fat, losing weight, looks happy/strained/fit/not fit.’ They show her living a life we do not know and at times cannot understand. We see her busy with strangers and sometimes we feel jealous that someone else has her attention and we pray, ‘Help us to understand.’

Missionaries in our own way

Trying to understand why our daughter has chosen this path takes up a lot of our energy. One thing, however, which is the direct result of her action, is to make her parents into evangelists. When we’re asked how she is and what she’s doing we have the opportunity to spread the Good News to acquaintances with whom we’ve never spoken of matters of faith, and it’s surprising how interested they are. God works in wonderful ways!

We’ve learned to pray as we’ve never prayed before and in talking over our fears and uncertainties with Our Lord we’ve come to know and love Him better. Our distant involvement with the lay missionary process has disturbed our comfortable lives, made us aware of the world outside, and we’re humbly thankful to have been called to play a small part in the work of the Gospel.

Father Joeker

By Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

Saved by my weight

At Fiumicino Airport in Rome, my suitcase was just a little over the allowed weight. I tried asking for consideration but the woman at the check-in counter looked adamant. I pleaded so desperately that finally she considered my request after casting a merciful look at me, a poor underweight fellow. My skinny structure must have made up for my excess baggage.

Coming of age

Coming out of the refectory for breakfast, our cook gave me a puzzled look and asked me why was I bringing the pitcher with me. Only then did I realize that I had picked up the pitcher instead of my Breviary, which I usually put beside the pitcher on the breakfast table. I must have had so many things on my mind that morning. Or maybe I’m already getting old – er.

Lessons in waves

I had never experienced a ‘heat wave’ though I had read an article about it. On our way to Takpamba, Togo, Fr Anthony Dindo was covering his ears like a Japanese tora-tora pilot swooping over Pearl Harbor. I was making fun of him throughout the trip, but he just ignored me. All of a sudden, a very hot breeze swept through the windows of the car. I ducked down, scrambling for a towel to cover my head. Now that must be the “heat wave”…I had to learn the hard way.

Beat this

I was having breakfast with a number of computer wizards one morning. The discussion was all about what the latest was in computer technology. ‘I have a computer that prints out four copies at once,’ said Fr Francis. There was complete silence. Everyone was dumbstruck – but me. I instantly knew what Fr Francis meant because I also own that kind of ‘computer’ so I blurted out excitedly, ‘Yes, it is true. I have the same model and in fact it can even print six copies at once! And it also talks a lot.’ Our bursar, who was known for his computer expertise, could hardly believe it. ‘I cannot figure out how that computer prints out four or even six copies at once. It’s impossible.’ ‘No, it’s not,’ I said. ‘How about that?’ I asked, as I pointed at the typewriter. Our bursar raised his hands in exasperation.

First Filipino Monastery In Ghana

By Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

Archbishop Gregory E Kpiebaya of Tamale Archdiocese, Northern Ghana, flanked by two bishops and an archbishop emeritus, together with about sixty priests, sisters and religious, blessed and dedicated the first Filipino Carmelite church and monastery in Ghana on August 8, 2002, in a colorful ceremony flooded with lights and flashes from videos and cameras. From beginning to end, three groups of choristers kept the celebration on fire singing alternately hymns in English and in local languages to the rhythmic beating of drums and tambourines. The monastery is the first missionary foundation of Carmel in the Philippines and the first Carmelite monastery in Ghana.

The Monastic Life

Appropriately, before the Liturgy of the Word, the archbishop gave a brief catechesis on the monastic life focusing on the purpose of the monastery and on some rules in the Carmelite way of life. He stressed that the Discalced Carmelite monastery is cloistered, meaning that the nuns live inside until death. In a related aside he mentioned that some monks in Europe used to keep their own coffin in their cell and would sleep in it once in a while to remind themselves that one day they would go. At this, a storm of gasps came from the congregation who were unfamiliar with the monastic-contemplative life. And to bring the cow back to normal, the Archbishop Kpiebaya hastened to add that there are times when the nuns are allowed to go out. For example, in times of sickness, they can be brought to the hospital or a doctor can be called in. In case of fire they can also run for their lives. This drew laughter from the people for whom bush fires and houses or whole villages on fire are a common sight during the dry season.

Gospel Interpretation

As the Mass continued, there was a unique gospel procession. An older woman clad in local costume, accompanied by two younger women in similar dress, carried the lectionary on her head in a nicely decorated basket with plates and foodstuff symbolizing that the Word of God sustains life. Following them were children aged ten and below and at the end of the procession were teenagers, all in local costumes and singing ‘Alleluia,’ dancing and swaying, buoyed up every now and then by an almost deafening yet melodious drumming made more dramatic by an occasional peculiar high-pitched shrieking from a woman in the group. Ironically, despite the noise, a strange hush engulfed the jam-packed church. One could feel the importance of the Gospel.

Spectacular Salvo

Then came the incensing and anointing of the marble altar and of the walls of the magnificent cone-shaped church modeled after traditional houses.

Not to be outdone, the nuns too had their gimmick. They had placed plenty of special explosive incense in a pot at the center of the altar. One of them then rushed forward…lit the incense and …Boom! Then smoke billowed, just like an atomic bomb in miniature. This shocked everyone momentarily but filled the air with holy fragrance. Later Fr Victor Leones SVD, our veteran missionary in Ghana, joked, ‘I thought the nuns were leading a suicide attack.’

Activity Sealed

Finally, after almost four hours, the lively ceremony ended quietly. To thank the people, Sr Mary Bernard OCD, Prioress, came forward and gave a message from the heart, showing the sincerity that is one of the many virtues the Discalced Nuns of the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mt Carmel are well-known for.

Congratulations to our Filipino Carmelite Nuns. We are proud of you! ‘You are Filipinos; you have tried well!’ as a Ghanian would say, paying the highest compliment. Pray for us, Sisters.

Fr Chapman, A Man For Others

Fr Francis Chapman, born in Fremantle, Western Australia, in 1913, studied Theology in Ireland and was ordained there in 1937. In 1938  he went with the first group of Columbans to Mindanao as pastor of Tangub, Misamis Occidental. During the War years he stayed in the mountains with the people. In 1950 he led the first group of Columbans to the southern part of Negros Occidental, an area that in 1988 became the Diocese of Kabankalan.

he went with the first group of Columbans to Mindanao as pastor of Tangub, Misamis Occidental. During the War years he stayed in the mountains with the people. In 1950 he led the first group of Columbans to the southern part of Negros Occidental, an area that in 1988 became the Diocese of Kabankalan.

From 1954 Fr Frank worked in Australia and later served as Regional Director there. He was a member of the General Council in Ireland from 1966 to 1970. He then returned to Mindanao and did parish work in the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro.

Since 1984 he has worked at St Augustine’s Cathedral there. Even with failing health, he still keeps up his priestly labors with great fidelity. Though now living in the Columban house in the city, he still spends hours every day hearing confessions in the cathedral. Turning 90 this July, Fr Chapman is the longest serving Columban in the Philippines.

Fr Chapman’s ministry has involved him in a special way with Men’s Catholic Action, the Legion of Mary, promotion of devotion to the Rosary, devoted care of the sick in hospitals and homes, and spiritual assistance to the wards of the Social Welfare Department and the Bureau of Jail and Management.

Wherever he has labored, the practice of prayer, especially the Rosary, has notably grown in families. Sacramental life and the works of mercy have flourished in communities and conversions have multiplied.

He has always shown gifts of leadership, never flinching from difficulties, ever cheerful and with a positive, proactive outlook in life. In every assignment, he has always given unsparingly of himself.

Recognizing the outstanding gift the Lord has given to the Filipino people, especially in Mindanao, in the person, life and ministry of a great priest, Ateneo University conferred the Bukas Palad award on Fr Chapman.

The award, formerly the Peypoch Award, honors Fr Manuel Peypoch, a Jesuit who arrived in the Philippines in 1907 and taught literature at Ateneo University for 17 years. The memory of this humble and dedicated priest and the many men and women like him prompted Ateneo University to create and award in his honor. Bukas Palad is intended to honor clergy and religious for their service to the Catholic Church and the Philippines.

Salamat sa Columban Mission

Happy Where I Am

By Sarah Young

Teria Cabalog is a ‘five-weeker’ – she has completed the five-week ‘Christian Community Workshop’ facilitated by the team of the Community Formation Center (CFC), Ozamiz City. She and her family welcomed me into their home in Barrio Estrella in January 2002. Their home is now my home. With Teria I attend the monthly meeting of the ‘five-weekers’ in Katipunan. I soon came to realize that the ‘five-weekers’ help sustain the small Christian communities under the wing of Katipunan Mission Station in the uplands of the Municipality of Sincacaban, Misamis Occidental. The agenda of the meetings is wide-ranging, from agricultural matters to the spiritual well being of the communities. The ‘five-weekers’ here are farmers and when not tending the needs of the community they are tending their crops and animals under the shadow of Mt Malindang, around which the province forms a semi-circle.

Last September the group suggested I attend the Five Week Seminar so that I might gain insight into the formation they’d received. I didn’t take the suggestion seriously at first. I babbled excuses about my skill in the language being insufficient at this stage and that I had commitments, scheduled that couldn’t be broken. They responded in unison, ‘Sulayi lang!’ ‘Try!’

Reluctant participant

Within a week the idea became a reality and I found myself in Ozamiz introducing myself to the other 14 participants who wondered why this white, Western woman was among them. I was asking the same question. The five weeks stretching before me seemed like a huge expanse of time. I resolved to take one day at a time and just see how far along the road I could go. Not only would we be sharing the content of the course each day but also would be living together over the coming weeks in dormitory accommodation, sharing our meals and the daily chores. It was basic and I soon realized that any notion I had of maintaining any privacy was gone.

The days were long and full. Mass was at 6 am. Workshops and lectures kept us occupied until suppertime and sometimes beyond. As the days passed my Visayan vocabulary grew longer and my dictionary was well thumbed each evening. On some evenings it was very near my pillow as the tiredness began to set in. My four companions from Katipunan took pity on me and tried their best to fill in the gaps in my understanding with alternative words and phrases. Without them I wouldn’t have reached week five.

Enriched

But language wasn’t the only challenge. Within a few days I realized that there were other dynamics at work. Through personal sharing of life experience, exploring the option for the poor in Scripture and being enlightened about the history of the Philippines and the cycle of dominance from outside its boundaries, I felt incredibly uncomfortable. The wealth and privilege of my own background was glaringly obvious. For the first time, I was reading the Gospel from the perspective of the poor. Its power and relevance hit me in a way that it had failed to do in all the years I had received it from the perspective of the ‘first world’. I wondered whether I should really be present at all. All I could do in response to this feeling was to stay and listen.

Keeping up with the pace

Vic and Perla Yap, a husband and wife and Fr Boy Ugto, our facilitators, had made it clear that I should be involved at every stage of the journey alongside the group. The journey became more uncomfortable but like the roads up to Estrella I knew I just had to get through the mud and over the rocks and keep going. The group could have left me behind within a few days. There was a huge gulf between their experience and mine, and communication was sometimes hard. I remained part of the group, however, and felt a growing sense of humility and privilege at being allowed to do so.

Personal sharing

In the ‘deepening groups’ where personal life experiences were shared I listened for two days to the most powerful stories. My companions told of their struggle to support their families and many related disturbing scenes of violent encounters in the home. I wondered time and time again what I would say when my turn came. When it did I simply spoke about my own family and about what it had been like to leave them to come to the Philippines. Since I came here my father has been quite sick and I expressed my feelings about this and how my parents continued to support my decision to be here. At the end of the sharing a young farmer said that when he saw me on the first day he questioned why I was there. He admitted that he had prejudged me. He had simply seen a rich, white person, ‘But now,” he said to the group, ‘I’ve heard Sarah’s feelings and thoughts about her family and they’re just like mine. She is now one of us.’ I was very moved by his words and knew that I couldn’t give up despite my own discomfort.

Getting to know one another

The group grew closer and I witnessed different characters come to the fore. The shyness began to fade and each of us grew in confidence as our contribution was valued. The wealth of talent within the group was a joy to see and it was exciting to think that this energy might be channeled into the small Christian communities in some of the remote areas of Mindanao. It was evident by week five that deep friendships and, for some, romantic liaisons were forming and we threw ourselves wholeheartedly into the creative drama workshops, thoroughly appreciating the presence of each other. We enjoyed relaxation and healing as we explored alternative health remedies. I was very glad of the massage to take the strain and tiredness away. For me, the five weeks had been a microcosm of my time in the Philippines to date. I had revisited every emotion and it seemed to have had a greater intensity in such a small group and confined space of time. I will never forget the trust and companionship that was formed during those five weeks with An-an, Bhoboy, Luz, Lorie, Mila, Rita, Mayeth, Doydoy, Enan, Jojo, Agustin, Toto, Vince and Nards. I am sure that, like me, they are still working out the implications of having attended the seminar now that they have returned home.

Within a few weeks of our graduation Fr Boy Ugto collapsed while celebrating Mass and died later that day. I attended his funeral in Dipolog Cathedral with the ‘five-weekers’ from Katipunan. In her testimony, Perla bore witness to Fr Boy’s service to building small Christian communities through the development of leaders who were yano, simple, humble people. She asked the ‘five-weekers’ present to stand up and make themselves known. I was proud at that moment to stand up as a ‘five-weeker’ and felt I had some understanding of the journey that those who were also standing had made in order to serve their communities.

Mosquitoes In Mali

By Frances E. Edillo

Mali, a west African country that straddles the arid Sahara in the north and the semi-arid Sahel in the south, has a land area more than four times that of the Philippines and a population of less than 9,000,000. Frances Edillo, from Southern Leyte, on leave from the University of San Carlos, Cebu, is working on her doctoral thesis at the University of California, Los Angeles.

I did research fieldwork every July and August from 1997 to 2000 for my PhD project entitled, ‘Population Dynamics of Malaria Mosquitoes, Anopheles gambiae Giles complex, in Banambani village, Mali, West Africa’. Malaria is a life-threatening parasitic disease transmitted to humans through the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito. In Africa, three mosquito species are the primary malaria vectors: An. Funestus, An gambiae s.s (sensu stricto) and An. Arabiensis. The latter two are morphologically similar and are called the sibling species of An. Gambiae s. l. (sensu lato). The World Health Organization estimates that there are 300 to 500 million clinical cases of malaria worldwide each year, about 90 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, with one to three million deaths. The disease also causes economic growth to decrease by 1.3 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Need for malaria control

Studying the population dynamics of these mosquitoes is very important for malaria control, particularly that its toll is growing. Mosquitoes develop resistance to insecticides; the parasites become resistant to preventive and therapeutic drugs and a successful malaria vaccine does not exist. Poverty and a lack of education, together with social and ecological disruption, hinder the application of current control measures.

Banambani is the standard site for malaria research in the Northern Sudan savanna, an eco-climatic zone, and the villagers are well used to foreign researchers. My project dealt with the population biology of An. Gambiae s.s., its molecular forms, and An. Arabiensis. My role in the overall collaborative project was to analyze the spatial distribution of the mosquitoes and to estimate the survivorship of their larvae within a single village. This was to enable us to understand their ecology and population dynamics. This is important in predicting the fate of introduced genes in the overall project, which was the experimental release of genetically engineered mosquitoes into the natural population for malarial control. The basic principle of genetically altered mosquitoes is to turn disease-carrying mosquitoes into harmless pests. If such ‘transgenic’ mosquitoes were genetically fit but unable to transmit the malaria-causing parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, and if they could be introduced into natural populations at a high enough frequency, they might transmit the malaria parasite at a much lower rate. This would be an important proof of the principle, but the road ahead is still long.

I spent many days mapping mosquito breeding sites and collecting specimens under very difficult condition in Banambani, with its sub-optimal infrastructure. The village covers an area of over 600 by 2,000 meters and is 20 kms from Bamako, the capital of Mali. It has about 700 inhabitants occupying 250 dwellings grouped into 70 compounds. There are four types of dwelling: round huts with a conical thatched roof, round huts with a flat mud top, quadrangular huts with a sheet metal roof and quadrangular huts with a flat mud top. Each compound houses an extended family in this polygamous culture. The rainy season is from mid-May to early October. Rainfall usually ranges from 830 to 1,100 mm during 81 to 89 hours of rain, with an average monthly temperature of 26 to 29 °Cand relative humidity of 68 to 74 percent.

I learned the local language, Bambara, in a crash course at UCLA before going to Mali. To my surprise, the villagers were very happy that I was able to speak their language well enough to greet them with, “I ka kene?” (How are you?) and such. With a smattering of other phrases I could explain to them what I was doing and its relevance in understanding the biology of malaria.

How the villagers live

I observed many forms of unfreedom such as malnutrition, little access to health care, sanitary arrangements and clean water, inequality between women and men, and a lack of education, among others. The well the people used as their source of water was less than ten meters from their toilet pit. Women washed clothes and dishes in the river and even in small ponds. Children enjoyed swimming in the swamp. Women did the household chores, cooked food, took care of their children, and walked downhill every week to the market in the next town, around 10 kms away, with baskets of fruit on their heads. Most men and boys farmed.

Simple life, simple joys

Despite the material poverty, I was always energized and touched by the simplicity of the people’s hearts and their warmth and joy in appreciating the little they had. For example, for my health’s sake, I usually brought canned goods whenever I camped out in the village. Once the cans were empty, children asked me for them. Within half an hour or so, the flat sardine cans had become little “carts,” the kids joyfully running around and playing with their new toys. Every time I finished my fieldwork, I gave away some of my t-shirts and slippers. One old woman was so happy that she gave me a pair of earrings. I was touched by that reciprocal generosity. The following year when I resumed my fieldwork, they specially wore these shirts to show their appreciation and that they had taken good care of them. Always with a smile, they courteously greeted each other and the tubabu, foreigners, with “Ini sogoma” (good morning), “Ini wula” (good afternoon) and “Ini chè” (good evening). They were very warm and happy people and celebrated special days by wearing their best dress and dancing in the street. However, it pained me to see some of my fieldwork assistants coming down with malaria. My headache pain reliever helped ease their fever temporarily.

Overall, the whole experience enabled me to help some people who were really in need. This outweighed the hardship I faced in trying to do so. I’ve felt the pain of the extreme effects of poverty and lack of education in a way that is not just intellectual and academic but very human. I just offer to the Lord the findings of my project even if at this point the output is still in the form of manuscripts.

Our Hideaway

A venue for the youth to express themselves and to share with our readers their mind, their heart and their soul. We are inviting you – students and young professionals – to drop by Our Hideaway and let us know how you are doing.

Former Atheist

By John Marc Acut

Almost everyday a classmate or a friend would drop by and casually say, ‘You are an "atheist" right? Why the sudden change? This going to Mass and all seems so bizarre for you.’ In reply, I would give my usual smile and start my story…

Upon my entrance to the teenage world, I faced so many troubles. Aside from being so many, they were also very heavy. They included a 75 in my Integrated Algebra, a broken heart and classmates who did not accept me as one of their own. It all came so suddenly that my emotional defenses weren’t able to help much.

Then I stopped with tears in my eyes. I tried to talk to the Lord, but it seemed as if He was unreachable. It seemed as if He didn’t exist. A question formed inside me, ‘Is there a God?’

All the burdens in my life, which I wasn’t able to carry evenly, helped me arrive at a conclusion: God does not exist after all. He is just a scapegoat for all our problems, someone or something we point to in times of trouble and thank in times of happiness.

I was an ‘atheist!’ I stood firm in this belief and almost had no regrets. Well, almost – within those times of unfaithfulness, I heard a call behind my back. I heard a voice, which made me look at the Old Road once more, the Road of Christ. Yet, I still went on my way with head on high.

One day, in my Christian Humanism class, God called me once more. Our teacher talked about this Jesuit priest who had a conversation with a girl who was an atheist. The girl told the priest that her reason for not believing in God was the idea that goes: if God really exists, then why is there so much suffering in this world? Where is God in this evil world, this evil life, which we all live in? The priest then asked her, “What about faith?” She answered, “I guess I don’t have the gift of faith.” Such an answer gave the priest the opportunity to prove her wrong. “You said gift of faith.” Since it is a gift, then there should be a giver. A Giver of that Faith…”

My teacher went on, “Atheists who have this disbelief because they think that if there is a God, there shouldn’t be any suffering in the world anymore, are like a little child who looks at a half moon. Upon seeing the incomplete circle the child exclaims, ‘God made an imperfect moon. Look! The other side of it is dark.’ He only ‘sees’ the invisible side of the half moon and not the wonder of its light. Like this, atheists only see the troubles in life and not the goodness, the wonder in it. Despite all of the evils in this world, God’s love still outshines these things.” Hearing these words, I stopped, reflected and went to Mass.

God is very real after all. I thought that He silenced himself to let me drown in the sea of my own misery. Yet I learned that his silence only meant that He actually suffers with me. It wasn’t I who did the seeking. Instead, it was He who looked, found and called.

Now I’m trying to repair all the damage I’ve caused in my relationship with God. All I ask from him is his blessing, that I might face him on his altar with an unwavering faith and a heart on fire for his Greater Glory alone for the rest of my days.

The Horror Of Payatas

By: Fr Colm McKeating

The author, from Belfast, Northern Ireland, is Regional Director of the

Columbans in the Philippines.

The name Payatas evokes a horrible image: the 22-hectare, 22-to-45-meter-tall open dumpsite used to dispose of the daily garbage of Metro Manila. Located in a low-lying part of Quezon City, it was chosen about 20 years ago as a relocation area for the notorious ‘Smokey Mountain’ in Tondo, the similar dump and embarrassing eyesore close to the center of Manila. It was hoped that being less visible on the rim of the urban sprawl, it might lessen the impact of social squalor and perhaps become forgotten.

But over time, this mountain of garbage became home to about 80,000 people. Many of these, with no other options for survival, scavenge the waste for recyclables such as cans, plastic and newspapers to earn a few pesos a day. Disease and short life spans among these families are commonplace in the makeshift community ironically dubbed Lupang Pangako (the Promised Land).

An avalanche of garbage

On the fateful morning of 10 July 2000 an avalanche of rubbish buried the shanties where these people lived. More than 300 were killed. Payatas, the unwanted face of poverty, also became a symbol of devastation and death.

It was a disaster waiting to happen. Nature seemed to have colluded with human indifference and neglect. Ten days of torrential rains had brought floods to many parts of the city. All the attention was paid to relieving the plight of those in the affected areas.

Looming disaster

No one, however, had noticed what was happening to Payatas. The monsoon rains had loosened the packed garbage, and the dump’s massive base had become a seething quagmire. The inhabitants of hundreds of shanties huddled around the foot of the mountain of refuse remained unaware of the danger.

Ironically, conditions seemed to be improving when on the morning of 10 July the rains ceased and bright sunshine appeared. That’s when a rumble followed by two explosions could be heard. The mountain of garbage split in two, and the vast compost heap, a time bomb of methane gas, exploded. A massive landslide devastated the surrounding area, burying it in garbage and mud.

Aftermath

A few days after the tragedy, I visited with Fr Michael Martin and Won-Joung, a Korean Columban lay missionary. Our guide was Columba Chang, another Korean Columban lay missionary. Columba was no stranger to the people of Payatas: she had been living and working there for four years. She introduced us to friends and relatives of the dead. We met one 19-year-old man still numbed by the loss of his wife and ten-month-old son. We heard many other heart-rending stories, including one about a German couple who came to offer scholarships to the poor and lost their lives in the disaster. Their bodies had just been recovered that morning.

During our visit, our rescue services were still working to recover other bodies. Alongside, a wasteland stretched eerily untouched by the mechanical shovels used for pushing back the avalanche. Entire families and their makeshift homes lay buried beneath its six-meter-deep carpet of mud and slime.

Survivors deserve better

As I look back, there would be some cold comfort if it meant a lesson had been learned and something like this would never happen again. But there is no such assurance. Waste management for vast populations like Manila’s millions is one of the pressing problems created by rapid urbanization. Such disasters are not unique to the Philippines; two weeks after Payatas, a similar tragedy occurred in Mumbai, India. The frequency of these so-called natural disasters and the seemingly callous disregard by the powerful and wealthy towards these inhumane living conditions of the poorest do not inspire confidence that long-term solutions will be found.

Perhaps those who live and work around the dump will be relocated elsewhere. Maybe, as happened last time, the cycle will simply begin again in another inhuman environment. The people of Payatas, like us, have just one chance to live a life that is human. In a world where, for a minority, the problem is what to do with excess wealth, the survivors of Payatas deserve a better opportunity.

Salamat sa Columban Mission

‘Bago-ong Eksperyensiya’

By Sr Leticia Bartolome ICM

This is a privileged trip! I’ve neither passport nor visa nor do I have to pay travel tax to leave the Philippines. I haven’t seen anyone yet as I’m sitting in a dark and crowded place. In less than two hours we land in Hong Kong. I can’t see anything yet, though I feel movement around me. Finally, air and light enter. Aaahhh! The box is being opened. Will they let us out?

Clueless

A customs officer pulls me out, studies my appearance, holding me close to his face. Wrinkling his nose in disgust, he returns me and tightly closes the box. Someone comes and takes me and my companions on a bus. I’m tired and sleepy…

Point of destination

Waking up, I find myself inside a big sari-sari store. Am I back in the Philippines? Oh, I’m not alone. I see other bottles next to me. We’re on a shelf. ‘Oy, patis, you’re here too?’ I see familiar faces on familiar containers. There they are, suka, adobo, lechon sauce, sardines, kare-kare, otap, dried mangoes, even fresh saba, Goldilocks – polvoron, ensaymada. Suddenly a big group of Filipinos come in, noisily touching us all, shopping for Filipino products. Another group sit around a table and orderhalo-halo. Why, they can even order a Filipino meal here!

Alone but not lonely

Before I know it I’m left alone on the shelf. My companions are sold out. ‘How long will I stay here?’ I wonder. Never mind, I’ll just make friends with the others in the store. ‘Hi, tawas, coconut shampoo,Eskinol! What are you doing here?’

Several days pass. I’m not homesick at all. There’s much to learn by observing and listening to people who come in. The speak Ilocano, Cebuano, Bicolano, Tagalog, Chavacano, practically every language from Batanes to Tawi-Tawi. Sometimes I laugh with them in their joys and cry with them as they tell their tales of injustice and maltreatment. Listening to their family stories and their problems can be too much for me.

My bottled-up feelings

One day I hear a young girl’s voice asking, ‘Do you still have bagoong?’ Finally I’m leaving.

Now my life is slowly ebbing away. In a short time I’ll be gone and only an empty bottle will remain to be recycled with others. But before I disappear, I have some questions. Why are our people in the Philippines so much after foreign goods while those living abroad buy products from home? Why do our people suffer so much in our country and when they go abroad they suffer just the same having to do ‘3-D jobs’ – dangerous, dirty, demeaning? So many questions! I wish I had answers! I wish I could be of help! But what can a small bottle of bagoong do for the country?

Are you listening, Bayang Pilipino? Are you listening, leaders of the country?