January-February 2005

A Shattered Dream Of Freedom

By Jane Serdoncillo

Jane Serdoncillo is a Columban lay missionary who has been working in Britain since 2000 after three years inPakistan.

Jane Serdoncillo

Fresta, a bubbly, beautiful young wife from Iran, fled from there for fear of her life. I met her through my involvement with RESTORE, a project of Birmingham Churches Together, an ecumenical group supporting refugees and asylum seekers. My work has given me the privilege of listening to their stories, of journeying with women and of being trusted. My work involves visiting and making the initial contact with refugees and asylum seekers before linking them to one of the ‘befrienders,’ generous individuals who volunteer a few hours a week to help and support refugees and asylum seekers in their locality.

When I first meet Fresta she was tense, afraid, apprehensive but desperately in need of assistance. She lived in a house provided by the National Asylum Support Service with four other women asylum seekers from Iran, Iraq and Zimbabwe. She had been a victim of physical, sexual and psychological violence from her abusive husband and in-laws. Because she feared for her life she fled from Iran to Germany with the assistance of illegal traffickers and applied for asylum. By doing so she had, according to their culture and tradition, shamed the ‘honor’ of her husband’s family by leaving him. The only way for them to restore that ‘honor’ was to kill her.

While awaiting the result of her application in Germany, her dream of being free was shattered when her husband traced her in detention and began to constantly harass her. She had no option but to leave Germany. Again with the assistance of traffickers, she arrived in England and applied for asylum using another name. When this was discovered she was put in police custody for falsification of documents and forgery. She was released later but was asked to report to the police every week.

What followed next was a long and winding road while anxiously awaiting her fate. One day she received a letter from the Home Office (the ministry for justice) telling her that her application for asylum was rejected and that she was to be deported back to Germany where she had first applied.

I was greatly saddened and can’t ever forget the horror in her voice when she told me this. I haven’t heard from her since. I often wonder if she ever achieved the realization of her dream of being free, or if it remains only a dream. But worse, is she still alive?

An Evening With Mrs Misho

By Father Jude Genovia SSC

Father Jude Genovia’s missionary journey has taken him to Japan as a seminarian (1995-1997) and to South Korea as a priest (1999-2003). From there he went to Chicago, USA, for studies that he is now continuing in the Philippines.

One evening in May 1996, I was eating dinner with my Japanese host, Mrs Misho, watching the evening news as we always did. That evening it showed a group of old ‘comfort-women’ from the Philippines - women who were sexually abused by Japanese soldiers during World War II. They were demanding a public apology and some form of compensation from the Japanese government for the unimaginable atrocities done to them. Mrs Misho and I were silent and I was most uncomfortable. I felt we were both on the spot. I didn’t say anything and tried not to show any reaction. But deep down inside was this tremendous disgust for the Japanese and at the same time an overwhelming sympathy for the ‘lolas,’ the ‘comfort women.’ Meanwhile, Mrs Misho uttered some words of embarrassment and discomfort. I tried to let the news pass as if I hadn’t seen it. Just as we were about to finish the meal Mrs Misho looked at me and said, ‘Jude, on behalf of the Japanese people, I am deeply sorry for the terrible things we did to your women.’

For a second, I was wondering if I had heard her say these words. For a moment I was confused why she had said them. But when I looked in her eyes, I immediately knew that she meant them. I sat at the table speechless. I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know how to accept her apology in Japanese. But I did know that God had let that evening be very special. I felt a heavy burden being lifted from me. I felt peace going all through me. I felt a door opening inside me. Most of all, I felt my wounded history as a Filipino beginning to heal.

My journey to Japan began in September 1995, my first mission assignment outside the Philippines, with my classmate Rolando Aniscal, now a priest in Peru. We joined two Columban students from Ireland. Essential to mission is to know the language and culture of the people. It was very painful learning Japanese. Something blocked me from taking this beautiful language to heart. Something within me was resisting. It was only when I moved in with the family of Mrs Misho for my ‘home-stay’ experience that I discovered this. For a long while I didn’t realize that the painful stories I’d often heard from my grandparents and parents about World War II had placed a ‘wound’ within me. Reading history and seeing some of the sites related to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines had deepened this.

Mrs Misho was the widowed mother of two. Her husband had been a painter and her elder son is a sculptor. She was over 70 when I moved to her home, a devout Catholic, as are the family of her son who live in the extended house. Her unexpected apology opened the possibility of my ‘wound’ being healed. It also made me appreciate the Japanese people and their culture more. The pace of my learning the language advanced dramatically. It also gave a new dimension to God’s missionary call. I began to believe that God brought me toJapan not only to heal my ‘wound’ but also to become a ‘wounded healer’ to others. Even though my time with the Misho family was short, I was able to continue seeing them because I was given my pastoral assignment in their parish, St Mary’s Sekiguchi, the cathedral of Tokyo. I devoted my time to building relationships in and around the parish. Although my presence and participation in the parish were limited, it didn’t really diminish my ‘reconciling’ presence. The longer I stayed the more I felt the acceptance and care of the priests, sisters, the youth and those directly involved in parish activities. My reconciling ministry wasn’t confined to Sekiguchi parish. I volunteered at the telephone-counseling center managed by the Anglican Church set up to provide psycho-spiritual services to migrants in the Tokyo area. I saw it as providing a safe space for people, especially Filipinos, to seek refuge, support, education and healing. Being part of it was a source of joy and humility.

My healing journey didn’t end in Japan. On 29 December 1998, after my return to the Philippines, I was ordained to the priesthood with my classmate Father Rolando Aniscal, a very memorable occasion for our families and for the communities where we belonged. What was most amazing was that three months after my ordination I had three visitors from Sekiguchi, two Japanese and a Columban. They came to Cagayan de Oro City to share their joy in my ordination. My joy was overflowing. It was a sweet reunion. They visited my family. My parents, grandmother, siblings and nephews and nieces were all anxiously gathered in the living room when our visitors arrived. The house was filled with an indescribable tension when I took them to the living room. What followed next was something I found hard to imagine. After the formal introductions our grandma and the rest of my family reached for the hands of my visitors to welcome them, our grandma who had discouraged me from going to Japan, and our parents who were so anxious during my stay there warmed to them. Something was transformed in that meeting. An incredible breakthrough happened that day. Someone had allowed that brief but extraordinary meeting to happen. We proceeded to the Columban house where I celebrated the Eucharist in the small chapel. I felt the healing journey that had begun in Japan concluding that very special day. What a day to celebrate the joy of reconciliation! I believe that my family was not only reconciled with our wound of the past but also with our God.

My visitors left the Philippines knowing that I wouldn’t be going back to Japan but to South Korea. It was a sad day indeed. Though the possibility of being reunited was slim, we parted knowing that deep in our hearts there was a precious seed of friendship growing.

I share this small but very significant part of my life because I believe it became a defining moment in my call to missionary priesthood. I believe Christ called me to the Missionary Society of St Columban in order to carry out HIS Mission, a mission that didn’t end with his resurrection but which he commissioned his disciples to carry out to the ends of the earth. Part of that mission that I share in my missionary journey to South Korea can be summarized in the Letter of Paul to the Colossians:

Well then, reject all that: anger, evil intentions, malice; and let no abusive words be heard from your lips. Do not lie to one another. You have been stripped of the old self and its way of thinking to put on the new, which is being renewed and is to reach perfect knowledge and the likeness of its creator . . . Clothe yourselves, then, as is fitting for God’s chosen people, holy and beloved of him. Put on compassion, kindness, humility, meekness and patience to bear with one another and forgive whenever there is any occasion to do so. As the Lord has forgiven you, forgive one another. When you have put on all these, take love as your belt so that the dress be perfect. May the peace of Christ overflow in your hearts; for this end you were called to be one body. And be thankful. Let the word of God dwell in you in all its richness. (Col 3:8-10, 12-16).

You may contact Father Jude Genovia at genoviajude@hotmail.com or St Columban’s, PO Box 4454, 1099 MANILA.

From The Mountains To The Seas

By Sister Elisa C Caballero OND

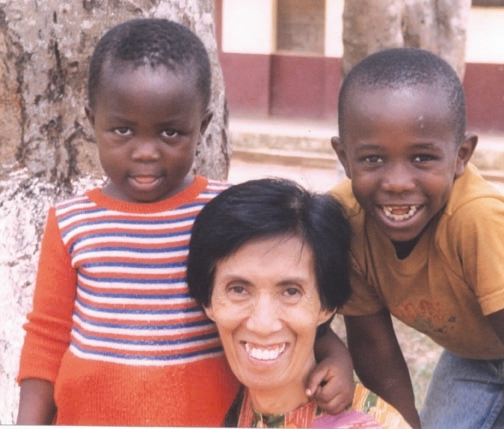

Sr Elisa on one of her home patrols in a remote village in Papua New Guinea

On 4 July 1995 I arrived in Papua New Guinea with great hopes and open to encountering a new culture and environment. I welcomed the many experiences of culture shock. After a few months of adjustment, and learning to speak Pidgin English, known in PNG as ‘Tok Pisin,’ I learned to let go, accept and understand the realities of mission life.

My first assignment was in Our Lady of the Star Mountains Parish, in a big mining town at the head of a valley where expatriates and local people are working hand in hand to make the Church alive and responsive to their life situation. After six months of easy mission life there, surrounded by modern facilities provided by the mining company, I was transferred to the high mountains. This gave me great joy for it was my wish to really live closely with the local people.

In the Solomon Islands, Sr Elisa travels by canoe

Thus, I started my journey with the people of the Min tribe in St Andrew Parish, set up in December 2000, or the ‘Mountains Parish’ as it’s called since it’s composed of far-flung villages across a mountain range. As the Parish Sister there for six years, I was involved in pastoral programs for the women, youth, catechists and prayers leaders, and in community organizing. I had no fixed structure to follow. Our ministry depended on the movement of the people, on the unpredictable weather and on events in the community such as deaths, births, planting, harvesting and so on. It was a ministry not so much of doing something for the people but of being with them . . . ‘wasting time’ with them, sharing their struggles, hopes and dreams for a better life. Most of the time, we were on the move from one village to another, traveling by small plane and often by foot across rugged mountains, valleys and swift rivers. It was during these ‘patrols,’ or pastoral visitations, that I gained a deep understanding of the culture of the people. I grew in patience with the endless waiting for the people, for the fog to clear, for the rain to stop, for flooded rivers to go down, for the plane to come, for changes to happen, and so on. My years with the mountain people made my heart sensitive to what people really care about, what matters most to them and what makes their lives meaningful, as well as what really matters most in my life as a missionary.

It was painful for me to say goodbye to the beautiful blue-green mountains and to all the people there who had become part of my life. With faith in God who constantly calls us to new life and surprises, I accepted a new assignment in January 2002, to a totally new life for me surrounded by the vast seas of the Solomon Islands. Here, I have no mountains, not even a small hill, to climb, no more cool, foggy and rainy days but sunny days with a very hot sun shining gloriously everyday. I also found myself in a very structured ministry of managing the Diocesan Pastoral Centre. I’m involved in planning formation courses for Church leaders, especially catechists, as well as budgeting and teaching.

The catechists in this very male-dominated society are all married men. They have a very important role in their communities as village and church leaders, and are responsible for almost every affair in the community and for the development of the faith life of the people. It is very challenging to facilitate an effective formation process for them. It wasn’t easy to teach them because of their cultural bias against women. During my first few months I was criticized and humiliated just because I was a woman. They couldn’t accept a woman managing a pastoral center and teaching them. However, there was a gradual change in their attitude towards me as well as a change in my way of relating to them. It’s still difficult to change their whole mentality with regards to women, but there is a growing awareness of the role and importance of women in their families and community. And my being a religious sister and missionary helped break the barrier. I hope and pray that someday women catechists will have a place in their Christian communities.

As a country, the Solomon Islands is still struggling to recover from the socio-economic and political collapse brought about by ethnic clashes from 1998 to 2000 and by massive corruption in the government. Economic recovery is very slow but peace and order has been restored with the assistance of peacekeeping forces from other Pacific nations led by Australia and New Zealand. It is indeed a real challenge for us missionaries here to journey with the people towards a better future and to recover their once ‘Happy Isles’ where people lived with dignity and in harmony with one another. However, in favor of localization, our OND missionary presence here is until this year only. It is indeed a sign of hope to see the local Church grow and take responsibility for ministries looked after by missionaries for many years.

Leaving a mission area is not easy . . . it always breaks my heart to say goodbye to people I’ve learned to love and who have helped me discover our Living and Loving God in the context of their culture. But I have to let go and be open to the Spirit to lead me to another place and to another people . . . for I always believe that God is with us wherever we are sent . . . and that God is in another place and in another face.

Honga

By Nelly D. Guinid

Mrs Nelly Guinid is the mother of Vanessa. Her father was a pagan high priest who asked for baptism when dying. As the Catholic priest was too far away, Mrs Guinid baptized her own father. You may contact her at NellyGuinid@dti.dti.gov.ph or at: bureau of Trade Regulation and Consumer Protection, 2nd Floor Trade and Industry Building, 361 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, MAKATI CITY.

The honga is an Ifugao practice where a dying person blesses his or her family. A day is scheduled, three to nine pigs are butchered and the relatives of the sick person, even up to the tenth degree, as well as the neighbors, are invited to take part. In the old days people prayed to the pagan gods to cure the sick person. The practice today, however, is to conduct a Christian prayer service, Catholic or Protestant, depending on the sick person’s religion, for his or her recovery. Immediately after the prayers, the sick person blesses by the immediate family. The number of pigs to be butchered depends on the economic status of the family of the sick person, whether rich, middle class, or poor.

Our Hideaway

GOD IS OUR LAST REFUGE

By Aida P. Lucasan

In complicated situations, we sometimes find it hard to let things go back to normal. We often just say,‘katalaka,’ and aren’t inspired to face life, which we think is a continuous and never ending heavy load. If we only try to recall and appreciate the best things that have happened in our lives, we can keep on moving forward. We can make our best efforts to help others as we serve God wholeheartedly. But most of us find ourselves looking back because we keep on recalling the trials and troubles we’ve experienced, resulting in self-pity instead of self-esteem.

Spiritually Weak

I had a friend, a jolly and good Christian companion. We were very close, as were our families. I saw her as my best buddy because she was always with me through thick and thin. But in spite of being strong, Michelle became a victim one awful day when her parents and two brothers died in a car accident. She wasbecoming strange, depressed and devastated, afraid to face life again with herbarkada. Worst of all, she didn’t believe in the existence of God anymore – her way out of her frustrations. Until she became sickly and infected by an incurable disease.

Repentance . . . A Parting Time

It was my desire to see good friends every time I went home. The first thing I did was to visit Michelle. When I entered the hospital ward I saw a flood of tears running down her cheeks, her eyes closed. I touched her forehead and she cried aloud telling me, ‘life is beautiful.’ I saw repentance on her pale and beautiful face for ignoring the challenges that God had given her. In a shaky voice she said clearly in a low tone, ‘God is good. I do hope He will forgive me for what I have done.’ I cried hard hearing those words from Michelle because I knew that this was the parting time for us . . .o:p>

A Gift Of Life Is Precious

IIt’s said that the journey of life is too short, that we need to squeeze out of it our best and to do such is for God. We should value ourselves in spite of our problems and trials and let ourselves open and get closer to God.

What happened to Michelle is a great lesson to those who take the gift of life for granted. We should always remember how God sacrifices for us and when we hear nothing from Him, our burdens in life are just a test. In tough times we need to surrender ourselves according to His will because after these trials we become stronger in facing life’s anxieties, doubts and problems.

Lastly, let me share this inspiring text Michelle sent me before she passed away: ‘God is too wise to be mistaken; God is too good to be unkind. So when you don’t understand, when you don’t see His plan, trust His heart.’

Spirituality And Imperfection

By Fr Michael McGoldrick OCD

Father McGoldrick is a member of the Anglo-Irish Province of the Discalced Carmelite, based inIreland. The Irish-Scottish and Nigerian regions of the province have a website at: www.ocd.ie . We thank them for the use of this article.

Begin to have more realistic expectations of ourselves, of others and of God. Learn to live less out of the expectations of others and stop taking responsibility for everything that is wrong!

Learn that it is alright to say 'No!' If people do not like us for saying no our world does not fall apart. We can have better relationships with others and we can have a more real, deeper and more fulfilling relationship with God.

When children are loved unconditionally they feel secure and grow up independent. They are aware of their self-worth, they are trusting and open. In decision-making they are confident; in conflict assertive. They are realistic in their expectations of themselves and of others. Their experience of God is of a loving and caring God.

What the child receives

These are the kind of qualities held up to us as characteristic of a 'normal' or 'healthy' child. But the reality is that most of us do not get unconditional love for many very understandable reasons. In fact very few children received unconditional love. Perhaps we need to take another look at what is the norm!

If most people do not get unconditional love during childhood then the norm is to feel insecure, to have an inadequate sense of self-worth, to be hesitant about opening ourselves to others, to be lacking in assertiveness in conflict situations. This has important consequences for us at an emotional and spiritual level.

Work in progress

Many of us have been crucified by the search for perfection. And the crucifixion continues! Advertising keeps reminding us of the perfect body, the perfect home….. We are constantly reminded by implication that we are imperfect. Can we turn that into something positive? If imperfection is the norm then we can begin learning to be at ease with imperfection. We are imperfect, others are imperfect, our world is imperfect - and all this is ok! This does not mean complacency. We are on a journey, which is slowly leading to personal transformation. We are a 'work in progress'!

We can begin to 'befriend' our imperfection, to be at ease with it. Failure does not make us bad people. We may do wrong but we remain good people. Accepting our imperfection means that we can acknowledge, accept and befriend our 'shadow' side: our overly competitive side, our dislike of our bodies, our shame, anger, inability to be assertive... We are of value for the person that we are - our 'shadow' side does not diminish that.

Just as we are

We are loved by others and by God. This has major implications for prayer. When we go to meet God in prayer we do so with empty hands - and know that God is quite happy with that. God does not want us to prove anything - just accept love. It takes a huge pressure off us! We go to God as a friend not as a judge!

The beauty of learning to live with imperfection is that our weakness becomes our strength! St Paulhad this insight nearly 2000 years ago! He wrote, ‘When I am weak then I am strong.’ We can become 'wounded healers'. Few people understand the weakness or pain of others like those who have had personal experience of them. They are in a particularly strong position to help, to bring healing to others. Their very ability to show their vulnerability invites people to come for healing!

To love our own self

But learning to accept ourselves is a slow process! We need to be patient with ourselves. We need to be gentle with ourselves. And we need to keep reminding ourselves we are not being selfish in doing so. All we are doing is treating ourselves the way God does!

There are many benefits! We begin to have more realistic expectations of ourselves, of others and of God. We learn to live less out of the expectations of others, we stop taking responsibility for everything that is wrong! We learn that is alright to say 'No!' If people do not like us for saying 'no' our world does not fall apart. We have better relationships with others. Above all we have a more real, deeper and more fulfilling relationship with God.

Trapped In Belgium

By Louis Marièn

Father Apolo de Guzman of the Diocese of Cabanatuan, chaplain to the Filipinos in the Archdiocese of Mechlin-Brussels, Belgium, sent this article. He is the brother of Father Efren de Guzman SVD and Sister Emma de Guzman ICM, both frequent contributors to Misyon.

She’s reduced to tears. She hasn’t seen her children for three years. Carina is a Filipino who worked as a housekeeper for the ambassador of an Asian country who locked her up in his house like a slave for six months. Washing, cleaning, cooking, ironing, from six in the morning to eleven at night. She was paid only €200 (a euro is worth about P70) per month while others were receiving around €500.

‘There are 5,000 Filipino migrant workers in Brussels. Seventy percent of them are women. And mistreatment is routine,’ says Father Apolo de Guzman, chaplain of the Filipino community. ‘The women in particular, and they are the majority, are sometimes the victims of exploitation. It’s not difficult for an employer to keep someone under their thumb. He can take away their identity card and work permit, and detain them. Housemaids have no way out. If they run away without papers, then they are here illegally.’

It’s not only domestic staff who can lead a dog's life. In some hotels and restaurants there are those who work long hours and days - overworked and underpaid and usually without the protection of social security. One of the scams is to register them as part-time workers while their work is full-time. ‘Some diplomats have their dogs and cats registered,’ says an angry Father de Guzman, ‘but apparently a human being costs them too much. If a Filipino chauffeur tells them he’s reached the age of sixty, he runs the risk of being fired ruthlessly, thrown out with the garbage. They ought to be paying him a pension, but if he has never had an employment contract, he is powerless to do anything about it!’

Many ‘illegals,’ not only Filipinos, have no social security protection at all. Sometimes they’re exploited, and sometimes not, according to our sources at the Labor Inspectorate. Some earn €5 per hour, but may have to pay €2.50 for expenses, such as room, food and coffee.

Others can open their own bank account into which part of their ‘salary’ is paid. As a guarantee that they won’t run away to other employers, they sign power of attorney in favor of their employer. Filipinos who work for consuls and ambassadors cannot rely on the protection of the Labor Inspectorate. Diplomats enjoy immunity! Fairness requires us to point out that employers such as the three US embassies have their personnel registered with the Belgian government. (As well as an ambassador to Belgium, the USA has one to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO, headquarters and to the headquarters of the European Union, EU, both in Brussels.)

Some Filipino migrant workers are here illegally. ‘There was an opportunity for them to become legalized workers with government legalization in 2000 but everything went fast,’ says Father de Guzman. ‘Those who worked six days a week, and had only Sunday off, didn’t have the chance to have their papers processed by the government If we hadn’t run a campaign on regularization after Sunday Masses here, only a few of them would have been able to put their papers in order.’

‘Filipinos are honest. You only need to ask the police and they will tell you they have no complaints about them. They are sought after as employees because they work hard. They help the economy progress. It’s really an outrage,’ says Father Apolo, ‘that people have to give up so much in order to give their children food to eat and an education, because that is why they are here in Belgium. It’s time that the Belgian government gave them protection against exploitation and gave them another opportunity to be regularized workers. It’s a matter of elementary human rights.’

Working Sisters

By Little Sister Goneswary Subramaniam LSJ Sister Gones stars with a quote from the mission statement of the Little Sisters of Jesus to which she and Sister Annarita belong. You can find out more about their congregation at http://www.rc.net/org/littlesisters/

“Because of Jesus and His Gospel, in a desire to follow Him closer in His 30 years at Bethlehem and Nazareth, the communities of the Little Sisters place themselves among the ordinary masses of society, may it be rural, urban slums or elsewhere.”

One of them

I’m one of these women scattered in small communities in 67 countries around the world. We try to answer this particular call, mainly by being manual workers. I come from Sri Lanka, where I joined the group in1989. Most part of my religious life I have been a worker, and still I am. I’m in the RP since 11 years. I’ve been through different jobs. Since 2000 I’m a sewer in a small garment factory in Q.C.

Our company is 18 yrs old, produces women clothes of good quality and style, for special occasions. They are distributed nationwide by buyers, who get them on whole sale and can really make big profit. Since last year we are also making clothes for another company under the name of “Initials”: these are sold in leading department stores in Metro Manila.

Their sad condition

For the workers there is no contract, one has to fit into the system. Wages are very low, sewers are paid by piece, each one makes the whole dress. One receives an average of 100 pesos a day, depending on the style. During peak season which is usually Sept-March, we are forced to work 12-15 hours without overtime pay. The stay-in workers are asked twice a week to go on a 24 hours shift, without overtime pay. Finishers, where the product is trimmed, ironed and packed, get 2,000 a month, plus free board and lodging. Since last year our conditions have improved a bit.

When I was new this situation seemed normal, nobody dared to speak to the boss, even less to the supervisor who is even harder to deal with. Eventually we started meetings with the boss. Some workers left, the situation has improved a bit, there had been tiny increases, and since last May most of us have SSS. It was a long and painful process, but it was worth it. If one of you will bump into us one day you might still find the situation harsh, but it’s getting better. There is hope.

Real Lessons from real People

I see in it a speck of the wider reality in many parts of the world, to which we belong as workers. These simple women have taught me a lot about life, much more than what I learned in books. Most of them are mothers who left behind in the province their families, and can seldom visit them because it’s too expensive to travel, they would rather send home the salary. They might not go to church, most of them, but deeply believe in a God who will never abandon them, and this gives them the courage to go on.

What else can I say, if not that they’re so precious in God’s eye?

Sister Annarita Zambone LSJ is from Italy. The article uses the term ‘domestic workers’ rather then ‘helpers’ since they aren’t volunteers but employees owed a just wage.

By Little Sister Annarita Zamboni LSJ

From the time I was searching how and where to invest my life at the service of God’s kingdom, I felt attracted by a life-style that can “show’ rather than explain or teach Jesus way of being among us: God’s love for the unloved, un-influential people, the “little ones” of our world.

I’m always amazed to that when God decided to be one of us in Jesus, He spent the longest time of His human life –30 years out of 33!- in a way that cannot be recorded because “it doesn’t make news”. The gospels say very little about his 30 years in Nazareth, where He was just “one among the others”, the son of the carpenter. Did He waste His time?

I was fascinated to discover the existence of a religious community who tries to imitate these long years of Jesus life.

Here among us

Right now, my Nazareth is in one of the many urban poor areas of Quezon City, where with the other sisters of my community we are renting a small house, with the desire to discover how God’s kingdom is “already here among us”, trying to pay attention to the silent signs of its growth.

As far as we can, we try to live like our neighbors, working to earn a living, facing challenges, struggles and hopes of every day…from small things (like the heat aggravated by the tin roof, or crossing the mud when rain pours made worse by the road-widening work ), to the more difficult search for a lasting work that could give some security to growing families, and dignity to parents struggling to face their responsibilities, often forced to work as OFWs. It’s so sad to find only underpaid jobs or to keep moving from a 5-month contract to the next, often working 12 hours for a minimum salary, 6am to 6pm one week, 6pm to 6am the next.

Living like the rest

I’ve been working for some years now, “laba-plantsa”, paid on a daily basis., in different houses and families. It’s a kind of part-time job, so I can have some time for the neighbors and for house work. The other sister is working full time (6 days a week). At the moment we are only two, but the community is usually made of 3-4 sisters. We try to always have time together for a meal and prayer, two kinds of nourishment that we daily need, beside the time that each of us reserve for personal prayer every day. This is very important, to qualify our presence to people and bring to God each one of them.

Looking back, I can now see how precious this work as laundry-woman has been, helping me to enter the culture, while offering many occasions to communicate values and messages from the Gospel.

I was able to discover that families who respect and value their helpers can easily overcome the initial embarrassment to hire a “madre” to do their laundry, while this is more difficult for those who take the helper for granted and are used to put on the religious and priests on a pedestal. But it has never been a problem to be understood and accepted by the helpers themselves, and they are actually the ones telling me what to do in houses where I’m “the extra-one”, just for the day of ironing, or laundry.

Hard labor, low pay

I was touched by the spontaneous reaction of a neighbor when we decided to move into this kind of work, who said: ‘Now, sister, I can understand: you’re really like us, in need of money. When you want, I can bring you with me, so we can work together and share the salary, in case you need more days of work.” She was so proud that a sister can do the same kind of work, of which she often felt humiliated. Laundry is the last resort for mothers in poor areas, when they badly need money to feed the family.

The sad reality is the ‘gap’, so evident and striking, when a middle class family can give to the daughter going to college much more, even double, as pocket money, but can give much less to the laundry woman who might work long hours with heavy laundry and has plenty of children to feed. This seems so normal, that when once I questioned it, I was made to feel as if I’m the one out of place.

Face without a name

Some ‘staying-in’ helpers, often very young girls coming from the province, who can hardly have a day-off, are seldom allowed to go out, or to make friends. Some might stay for years before going home for vacation. Not to mention when the ‘Ma’am’ borrows money from them or withholds the salary with an on-going promise to pay. At times they might be abused by their own family in the province, just asking for money… No surprise if some of them get lost in the big-city, easily cheated by promises, hungry for affection.

Many stay-in domestic workers can’t make any decisions, have a private life, or even have a name. they’re often known as ‘katulong ni.’ I know of one who didn’t even have a picture to be put in her coffin when she died!

Where Jesus would choose to be

I treasure some real ‘pearls’ I’ve received from them that they were unaware of, hidden in the soil of their lives I also treasure the deeply evangelical approach of many truly Christian families, concerned that their young workers were not able to finish their studies, and looking for ways to improve their situation, besides making sure that once in a while they could go home. There I can rejoice in the presence of God’s kingdom.

It’s not the kind of work we are doing, but being valued and respected as persons that gives us dignity. This is the message we want to communicate to those who often feel humiliated by their conditions, and are ashamed to answer when asked about their occupation or address. Where would Jesus choose to be if He came back today?

Just like Mary of Nazareth

When John the Baptist from the jail sent his disciples to ask Jesus if He was really ‘the One.’ Jesus sent them back with the greeting ‘Blessed those who will not be scandalized because of me.’ I often think of this when pious people find difficult to understand our style of religious life and ministry. I’m reminded that all of us have been shaken now and then in our pre-conceptions of God. It has happened often during Jesus life, and it will continue to happen if we are open in our faith-journey.

I often think of what might have been the life of Mary in Nazareth. I Feel so close to her fetching water, invaded by children while I’m preparing a meal or fixing the house, and I ask her to teach me how to discover God’s ways by treasuring what I hear and see and pondering it in my heart, as she used to do.

‘Hidden’ Women

By Rowena ‘Weng’ Dato Cuanico

Rowena Dato Cuanico is a Columban Lay Missionary from the Philippines on her second term in Fiji.

When Beth Briones, another Columban lay missionary from the Philippines, and I arrived in Holy Family Parish, Labasa, on our first term, we spent our first six weeks at Holy Cross Catholic Community (Sector 11) in Naleba. This was to help us understand better the culture of the Indo-Fijians as well as improve our fluency in Fiji-Hindi. Being new, I felt very excited in getting to know the community. Since their names were foreign to me, remembering them and pronouncing them correctly became a challenge.

On our first Sunday in Naleba, we were introduced to the mostly Indo-Fijian community. However, I was surprised when few of the women were introduced by name. Most were simply the wife of their husbands, ‘Samuel ke aurat hain,’ ‘Samuel’s wife.’ That is how I first got to know the wives of Samuel and other men. Having to remember only the husbands’ names certainly was a lot easier, but I kept wondering – don’t the women have names of their own?

At that time, I was staying with Aunt Lila and her son, Semi. Aunt Lila has a remarkable knowledge of our community. She was helping me a lot in learning the history of Naleba, the relationships among the different families, as well as in getting to know our Muslim, Hindu and Anglican friends. But there was one thing that I felt passionate about – knowing the names of the women. So, we decided to learn their names. Surprisingly, some proved difficult even for Aunt Lila to remember, maybe because they were hardly ever heard.

Then she explained why. When an Indo-Fijian woman marries, she becomes part of her husband’s family. The woman leaves her family, literally. Some even receive their inheritance on their wedding day because on that day they ‘cease’ to be part of their own family. This explained the crying and even wailing of the bride’s family in a video I saw.

Some women, particularly in the old days, were not even allowed to see their families again, except maybe at a wedding or funeral. A woman who could visit her family any time was lucky. While times are changing, some still practice this part of their cultural tradition.

In Indo-Fijian culture, the wife is expected to follow the religious beliefs of her husband. Some Catholics married to men of other faiths no longer come to church. But there are also many women who have become Catholics after marrying Catholic husbands.

However, I learned from Aunt Lila that women do have influence in the house, although in subtle ways. Most children talk with their mothers first rather than going directly to their fathers. This position in the household thus gives them influence and authority.

With these cultural notes, Aunt Lila and I started learning the names of the women of Naleba. Slowly, I got to know Indra, Samuel’s wife, Baby, the wife of Deo Dass, as well as Roshni, Rina, Jyoti, Sheryn, Rosa, Shobna, Rosa and Margaret. Their names are beautiful. Indeed they are beautiful and hardworking women.

When Aunt Lila and I came to Mass two Sundays later, we started calling the women by name. Some looked surprised while others were amused that we knew their names. We could only smile. It was a breakthrough, a beginning. Since then, we try to call each member of the community by name.

Other good things began to happen in the community. Some women took responsibility in reviving the mandalis, prayer groups. They, with their children, became more and more active in preparing the liturgy, some leading the choir, others serving as lectors and commentators. In July 2002, Aunt Baby, a convert and wife of Deo Dass, was commissioned as a eucharistic minister, the first woman in the community to be such. Since then, Florence Raj, a teacher, has been elected as vice president of Holy Cross Catholic community.

The names of the women can finally be spoken and heard and are at least now known to the whole community. To a certain extent, they are hidden no more.

‘Jesus, Je T’aime’ ‘Jesus, I Love You’

By Sister Emma de Guzman ICM

Kwada is 4-years-old and her brother Kodji 6. They are the two youngest of a family of eight children of Delu and Kudji, the couple working with us at Okola.

Different tongues

When Delu and Kudji arrived from north Cameroon about 15 years ago, they had only two children, Tije and Mossi. Tije was left in the north and Mossi, then a little girl of 4, grew up with us. When her parents were very busy, we in the community baby-sat her and, later on, the other children. In my baby-sitting time, I taught Mossi how to say short prayers. The shortest was ‘Jesus, I love you’ in English and French. I then added it in Ewondo and then in other languages. The two youngest children, Kwada and Kodji, can now say it in 12 languages.

We began like this: Jesus, je t’aime, French; Jesus, I love you, English; Jesus ma din wa, Ewondo; Jesus, mahal kita, Tagalog; Jesus, ayayaten ka, Ilokano; Jesus, ik hou van u, Flemish. We were Filipino and Flemish Sisters in our ICM community then.

The Sisters or the parents would ask them to recite their prayers for visitors. Amazed by the children’s intelligence, missionaries of other nationalities passing through Okola added their languages which the children eagerly repeated. Gradually their repertoire included: Jesus, Ich liebe Dich, German; Gesù, ti amo, Italian; Jezu, moj kochany, Polish; Jesus, na rnag gayo, Rhumsu, their mother tongue; Jesus ga kungu, Bamileke.

Leader of the gang

I told Mossi as she was growing up – she’s now in high school - that it was her turn to teach her younger brothers and sisters this Jesus prayer in the different languages. She did this very well. The list goes on to this day in the year 2004 with Kwada and Kodji, the two youngest children. Would you like to add your language?

Meanwhile, we’ve become too busy and as there are more children we can no longer baby-sit. Sometimes, however, the children pray the rosary and vespers with us. The attention of the younger ones being short-lived, we allow them to stay for the rosary saying their own intentions and only ten Hail Marys. Then they say their Jesus prayer. I’m amazed to hear the original four different languages now multiplied to 12 to the extent that I can no more follow. And they end in French with ‘Goodnight, Jesus, Goodnight, Mama Mary, Goodnight, Joseph.’ Then off they go and we continue vespers with the older ones.

My simple joy

However, Kwada and Kodji seem to be the brightest of the children. I taught Kwada to answer,‘Emma, me voici,’ ‘Here I am,’ when I called her ‘Kirikou,’ the name of the central character, a tiny little boy, in an animated film based on a West African folk tale ( www.kirikou.net ). One time somebody in the mission called her that name and instead of answering the usual, ‘Here I am,’ she retorted, ‘Who taught you that?’

These are just some of the joys of living with Delu’s family in Okola and seeing the children grow up with us.

Gift of children

At the beginning we tried to help the couple practice family planning as the health of Kudji was in danger, but they said their children were their riches. So now they have eight. Truly, their riches are ours too. Children here in Cameroon are runners for their elders. Approaching 30 years in Cameroon, having arrived in 1975, I can no more run back and forth in the mission compound. So, like most parents and families, I will ask a child to bring or take this or that to someone. They’re also good security guards. We say that thieves cannot easily enter the mission compound when they see so many children running around and about.

But the most amazing is the Jesus prayer in different languages. The children evangelize their playmates and classmates whom they bring home by teaching them to say ‘Jesus, I love you.’

‘The face of my beloved christ’

BY FR ANTHONY T. PIZARRO CICM

My sister Chato made use of the image of marriage. A love relationship is at the very heart of marriage. My love story with God started in this chapel almost ten years ago. Young as I was, idealistic and full of passion, I found myself confronted with the classic question: What do I want in life? A very existential question that could have been answered by: marry your girl, rear a family, and be happy in your career. Or by: use your talents; make a lot of money; travel; be famous and powerful. A strange inspiration dawned on me while I was contemplating the question in this chapel a decade ago. Why not live a simple life dedicated to pure service and unconditional love for the poor and the lonely? The third option was appealing but I knew it was difficult and would entail much sacrifice on my part. Yet I was bent to give it a try, if only to fulfill a dream, if only to accomplish a mission.

So the love story started. From my home in Tuguegarao to Saint Louis College to Maryhurst Seminary and Saint Louis University in Baguio, from the novitiate in Taytay, Rizal, to the Asian Regional Formation Community (ARFC) in Manila. In between I realized that this love for Christ was showing me the real world of those who suffer. I lived with garbage collectors in Taytay, prayed with troubled fisher folk in Rizal, saw the plight of evicted, dispossessed and poor farmers in Tarlac, cried with the slum dwellers of Quezon City, sympathized with the prostitutes, the powerless and the forgotten inBaguio. I felt the agony of the victims of famine and natural disasters in the Visayas caused by wanton illegal logging, relentless mining and over-fishing. I saw the plight of the wounded and displaced in Lanao del Sur, was witness to the endless bloody clan rivalries in Marawi. I met the paralyzed and the abandoned in Manila, saw how homosexuals were discriminated against and unjustly marginalized. I cried with the victims of family disintegration and sexual abuse in the big city. I saw a world torn apart by greed and corruption, the selfishness and tyranny of the powerful few. I saw the face of my beloved Christ in tears and in pain as I saw my beloved Philippines drenched in agony and death.

Then I left for Belgium in Europe and later for Senegal in Africa. There I saw people strive hard to regain their dignity and honor lost through corruption in government and mismanagement, due to individualism, materialism, poverty, godlessness and abuse of power. I saw the face of my beloved Christ crying through thousands of girls imprisoned in a house where they were to be sold to the highest bidder. I saw how foreign workers were exploited by powerful employers, in the name of profit and greed. I saw God weeping in the millions of urban poor Christians, Muslims and animists inSenegal, Mauritania and the Gambia. I saw the poor, the sick and dying, the forgotten and marginalized, the downtrodden and the prostituted, the illiterate and the unhappy and unforgiven.

I saw how the world needed some relief and, more importantly, hope. I saw Christ, my beloved, in tears and deeply wounded and prodding me to offer my hand and my heart that I might be an instrument of his salvation and love for all. Nine years of getting-to-know-you, of ligawan, oftampuhan and selosan, of ups and downs, of deep engagement and of being soul mates. Nine years of formation putting on the heart of Christ and seeing the world as it is and trying to become a religious missionary relevant to this world in pain and in sorrow. It was a difficult journey to be formed by the One who called and sent me. It was difficult to sacrifice myself and always try to be of service to the people God loves most – the poor and the downtrodden. My love story was tough and very demanding.

Yet God showed me his wonders and his saving hands at work. He never failed to show me his love, to embrace me, to assure me, to care for me. I felt all this as I met people who unselfishly worked, toiled and plodded for the cause of the poor. I met generous and selfless government servants and civil leaders. I met religious sisters and missionaries, priests and lay collaborators who left home and comfort to help change the world. I met lay people who gave their time, effort and resources that the mission to alleviate the plight of the poor might continue. I met you, and all who time and again had thought of, prayed for and sacrificed a little of what little you have for the missions. I lived with Muslims, Christians and animists who, despite differences in color, culture, language, religion and convictions, share the same vision of a better, just and peaceful world. I was deeply touched by the testimonies and witness of thousands of men and women who tried to live to the letter the Good News of Christ’s salvation for every living creature, for every troubled soul, for this tired world of ours.

More than anything else I saw God in you. That has made this journey, mission and pilgrimage of mine, not only bearable but lovely, wonderful and very enriching. I came to know kind and beautiful people, to visit places I never imagined I would go to. I witnessed life-giving events that will forever mark my humble life. God was there, as He is here right now. The God who called me is the same God who has sustained me all through these years. And He continues to sustain me, enrich me, and surround my life with good friends. He clothes me with dignity and honor, and despite my human frailties and shortcomings, entrusts to me his mission to continue his plan of salvation for his people. What more could I ask for but to pray that He continues to do the same.

He continues to surround me with your support and friendship as I start my priestly ministry. God was and is and will always sustain me through you. And so accept my heartfelt gratitude to all of you who inspired me, challenged me, formed me, prodded me, gave me the gentle push, supported me, cared for me, trusted me, believed in me, comforted me, soothed me, loved me, prayed for me, and all who are here today to renew friendship and brotherhood with me. Surely God was and is and will forever be present in my life through you.

From the very bottom of my heart, I dedicate to all of you this ordination and this humble consecration of mine to the priesthood. I am marrying Christ, his Church and his missions, and forever I will consecrate my life to him. I want too to have you as major actors in this continuing love story with my beloved Christ. Do continue praying for me that this love story with our God may continue to be of service and be life-giving, and that it may make this world a wonderful place of peace, love and hope for our children.

Ta nikamu ngamin Dios mabbalo;

Ta nikayu ngammin mabbalat;

Kadakayu amin Dios ti agngina;

Sa inyo pong lahat, maraming salamat po;

To all of you, thank you very much;

A vous tous et toutes, merci beaucoup;

Ngir yen nepp jerejef bu baax- a-baax.

Father Joeker

By Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

WHAT’S HIS REAL NAME?

One Monday evening I had dinner at the Columban House in Singalong St. Manila. Sitting beside me was Maria, a Columban Lay Missionary from Fiji, working in Manila. All of a sudden while we were eating, she started texting the Misyon promoters, telling them in all excitement about me. They told Maria to ask me what the correct spelling of my name was, as they had been discussing this earlier. Was it ‘Joeker’? ‘Joker’? ‘Jawcare’? Well, well, well. Why don’t you just call me ‘Joe’?

PROFESSIONAL THIEF

The night before our scheduled visit to St Peter’s Square during the Jubilee Year of Families, we were cautioned to be extra careful of professional thieves, especially on the underground train. The thieves were so smart, we were told, that they could remove your socks without removing your shoes. ‘I think that’s a bit too much,’ I whispered to my seatmate who shared the same sentiment. Then coming out of the underground station, I saw Fr Hubert Wooning SVD, one of our older classmates, walking ahead of us in Angelica Street. Hastening my strides, I dipped my right hand into his pocket. He turned around in panic, freeing his pocket, while some of our classmates came to the rescue –- only to find out that the ‘thief’ was me.

PEACE DIES

I told my friend, Mr Paul of Akrobi village, about the death of my dog, Peace. His death really pierced my heart and left me sobbing like a child. Paul told me that in their cultural belief, if there was an impending misfortune, a good dog would offer its life to ward off the evil to its master. As a priest, naturally, I brushed aside such a comment. A week later I got an attack of malaria so serious that one of the staff had to be assigned to look after me the whole night. Thank God I survived. But, I was thinking, could it be that my dog had died to save me?

THE MANNEQUIN

I went to a supermarket in Cubao when I was in the Philippines for a vacation. I was looking at some items on one of the shelves and was standing closely to what I thought was a mannequin. Suddenly it moved and said to me, ‘Bili na po kayo . . .’ My goodness! I almost had a heart attack. It wasn’t a mannequin at all.