Misyon Online - September-October 2016

By Their Sickbeds

By Louland Escabusa, cicm

The author, from Pilar, Bohol, is a seminarian of the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (CICM). From 2011 until this year he was studying theology at CIFA - Communauté Internationale de Formation en Afrique (International Community for Formation in Africa). In September he is going to Hong Kong for a two- to three-year internship program.

Marina

Marina became a familiar scene. Every week there she was, seated on the bench just outside her room, often with her mother, a checkered shawl wrapped around her shoulders, her petite frame crowned with a contagious smile. The light in her eyes spoke of an enigmatic glee but couldn’t hide the pain and sorrow that almost gnawed away at her hope, her joy, and the very purpose of her being. Among the faces of patients that I encountered during my apostolate in the hospital hers was one of the few that left an indelible mark on me, making my apostolate meaningful and my integration in Cameroon enriching.

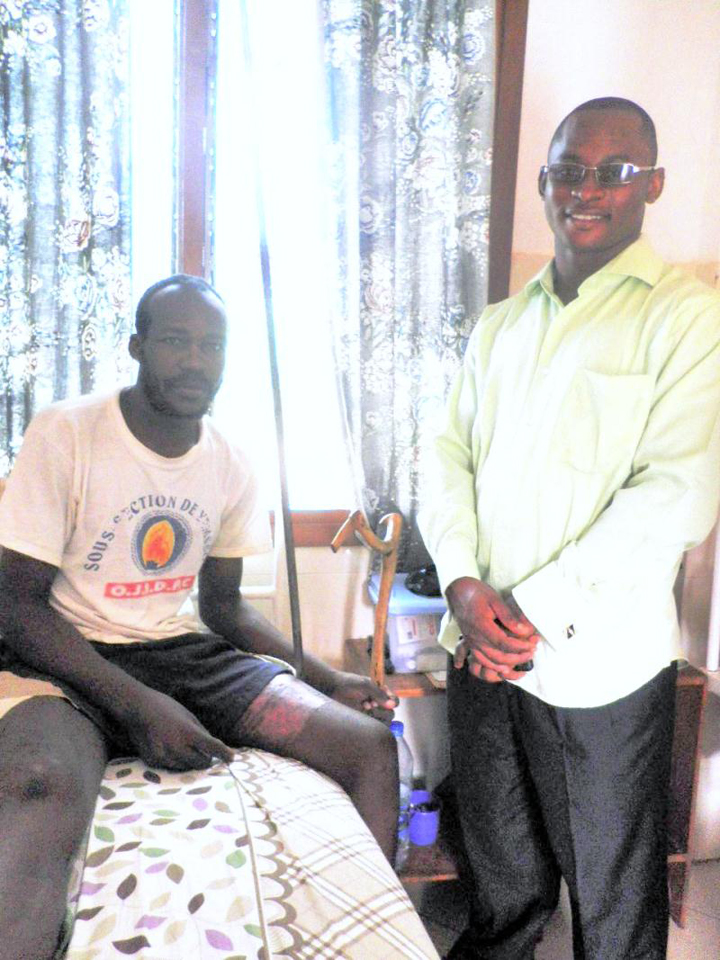

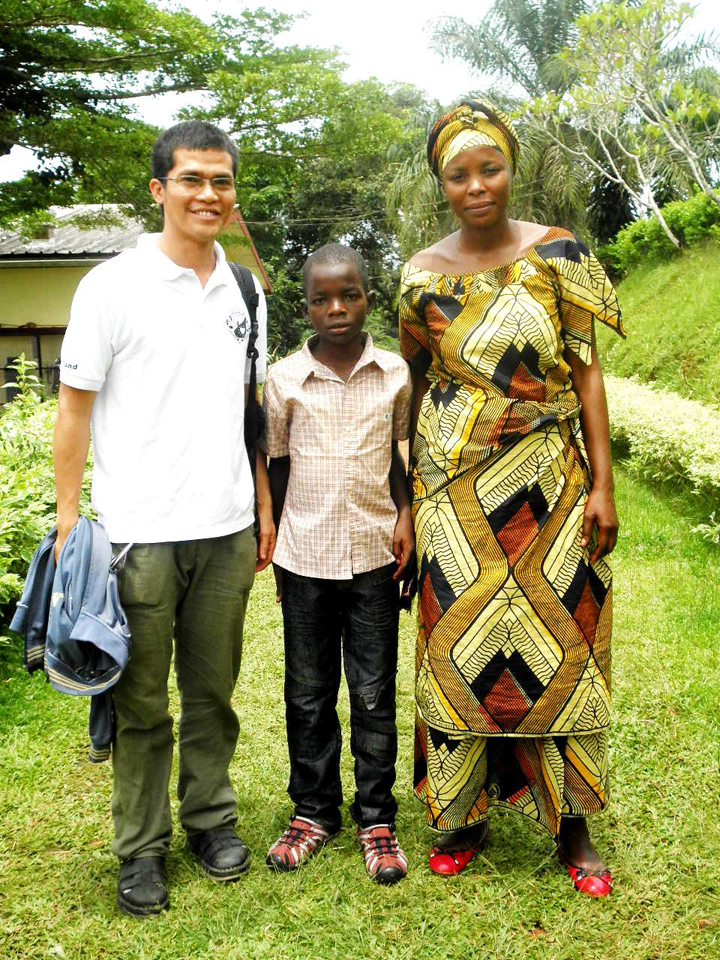

Emmanuel Mandona CICM visiting a patient

In our community of initial formation Saturday afternoons and Sundays are devoted to the Apostolate, one of the four pillars of our formation, Spiritual, Academic and Community Life, the others. I worked with two confreres, Amos Onezaire, a Haitian, and Emmanuel Mandona, a Congolese, at the Centre Hospitalier Dominicain de Saint Martin de Porres, located on a hilly periphery of Yaoundé, the capital, run by Dominican Sisters. The unpaved road leading to the hospital was a weekly challenge, with its literal highs and lows of humps and holes. If rainy we had to struggle through mud, if sunny through dust.

Our Lady of Victories Cathedral, Yaoundé [Wikipedia]

Our main work was visiting the patients. It helped that the three of us were of different nationalities and I blanc, white, as Cameroonians refer to non-blacks, because that was an easy starting point in conversation to put one another at ease. I usually approached the guardians or ‘watchers’ of the patients, who were usually in the corridor. Almost always, the conversation would start with a friendly ‘Salaam’ followed by a ‘Q & A’. I would ask what had brought them there and they would ask what a blanc was doing in the hospital. The conversation would then lead to topics as mundane as the weather, or to an assessment of the more than 30-year reign of President Paul Biya.

There were usually three to five patients in each room. The observation room, maternity ward and pediatrics section had room for more. The children in the latter had common sicknesses such as malaria and typhoid fever and, to my surprise, there were cases of hernia, common in Cameroon among adults and children.

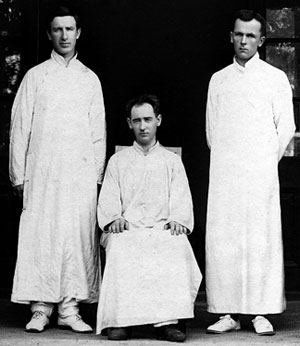

Louland with a patient

I learned from Marina, when we started our apostolate, that she had already been confined for more than a month. She had undergone an unsuccessful cesarean operation. The child was a girl. Marina had also lost her first child. The wound from the operation was already healing and Marina was hoping to be discharged soon and could have been an out-patient while continuing her medication. But she didn’t have the means to pay for her hospitalization. I was humbled by her openness. The father of her child had gone away after learning that Marina was pregnant and had made no contact since. Her widowed mother had traveled from their village a hundred kilometers away to watch over her. She had a sister Yaoundé who, from her limited means, brought them food time and again. When things were really tight, Marina and her mother relied on the mercy of other patients and guardians.

In one of our conversations Marina sobbed over the fact that she wasn’t even able to attend her daughter’s burial. Her grief was ‘suspended’ under one concern after another. She felt guilty over the loss of two children already, claiming that she must have sinned so much that her womb had become inhabitable for the innocent. And if the death of her child wasn’t agonizing enough, she felt abandoned by some relatives who refused to answer her calls. She needed help to pay the hospital bills which were beyond her capacity. ‘Had I died, all of them would have gathered before my dead body and contribute something for my burial. Why can’t they do that now while I am still alive and when I need it most?’

I truly felt for her and my inability to respond to her concrete needs made me feel very limited and my apostolate inadequate. Yet, we could only do as much. But at least we could let her feel she wasn’t abandoned.

Louland with a hospital worker and her son

Apart from a few patients like Marina who needed an extended period of treatment, each week I met new faces. This demanded a certain ‘audacity’ and a willingness to undergo a process from being strangers to companions, repeated every week. At times I was hesitant and still struggled with French. It would have been easier for me to coil up in a corner. Besides, there were times when patients even questioned my intentions. There were times when I felt that my presence or absence didn’t really matter to patients.

However, the great majority, like Marina, were welcoming. That was enough to motivate me. Like her, some patients were very open about their condition and the struggles they were going through. They could be very personal at times. I felt I wasn’t the right person for them to confide in. We usually shared the Sunday gospel with them invited them to pray with us. Some stormed us with questions about life in the seminary, or about daily life in the Philippines. In turn, they often described their life in the village where they were from or the circumstances that led them to hospital. This exchange was very enriching for me.

Mourning dance of Cameroonian women

The poignant events I witnessed spoke of the similarities and differences in the way we respond to events. It could be as universal as the unspeakable pride and joy of a first-time father, his daughter asleep in his arms. It could be as particular as Cameroonian women expressing their grief through dancing when a family member dies. It could be as specific as Onana, an amputee who rushed to the hospital upon learning that his brother had collapsed and taken there. It turned out to be simply a case of drinking too much beer after a football match!

I came to realize that I wasn’t visiting the hospital just to accompany the patients for they might have had little need of that. It was a companionship that some of them and I were building, an encounter of persons enriching one another. They helped me slowly uncover the wonders - and blunders - in the life of a young missionary in a foreign land. They showed me the reality of joy, sorrow and pain in a different context. Together we explored the intricacy of human relation in a milieu that, at first, I wasn’t familiar with. We weaved together our stories, the threads that made a beautiful tapestry of human existence. For all of this I can only be grateful.

A Pygmy couple at the hospital

As for Marina, I got used to seeing her sitting on a bench outside her room, often with her mother. But halfway through the third month of our apostolate she was discharged. I was just glad that, finally, she was out and, I hope, back to the normal rhythm of her life. That was how it was supposed to be. In our apostolate we didn’t say such things as, ‘Hope to see you next week,’ nor, ‘Until next time,’ nor anything suggestive of a longer stay in the hospital. We would only wish the patients well. We could only assure them of our prayers.

The stories of Marina and some of the others now play like a slideshow in my mind. I can only pray for them and wish them well. And I ardently hope that our encounters were as enriching for them as they were for me.

Pope Benedict’s visit to Cameroon 17-20 March 2009

Cameroon

National Flag [Wikipedia]

This Central African country covers an area of 475,442 square kilometers (Philippines: 300,000) and in 2013 had an estimated population of around 23,000,000 (Philippines 101,000,000). 40% of its people are Catholic, 30% Protestant and 18% Muslim (Philippines: 80.1 percent Catholic, 5.8% other Christian groups, 5-11% Muslim). Cameroon’s official languages are French and English, though it has 230 indigenous languages. The Deaf there use American Sign Language. The country’s major sport is football (soccer) and its national team has been one of the most successful of African countries in international competitions.

Our Lady Queen of Apostles is the Patroness of Cameroon.

Basilica of Our Lady Queen of Apostles, Yaoundé [Wikipedia]

St John Paul II visited Cameroon 14-16 September 1995

From my Own Ghetto into a Space of Solidarity

By Louie Ybañez

Louie Ybañez, a licensed architect by profession, is a seminarian of the Missionary Society of St Columban and is currently studying theology at Ateneo de Manila. He is from Agusan, Cagayan de Oro City, Mindanao, Philippines. He spent two years on First Mission Assignment in Pakistan from 2014 to 2016. Here are two articles he wrote, the first after returning to the Philippines and the second while still in Pakistan.

Louie (back row far right) with Asnawi Family, Sultan Naga Dimaporo, Lanao del Norte

When I lived in Pakistan I was part of the 1.6 percent who are Christians in this predominantly Muslim country of an estimated 203 million people. In Pakistan many Muslims have hardly even met a Christian and certainly do not know anything about the Christian faith. Nor are most of them even interested because it is not a major concern for nor does the Christian faith impinge on their daily lives. Prejudice among Muslims towards Christians and vice versa, is common because of the lack of willingness or even interest to engage with each other.

People in the Philippines, where I grew up, are inclined to have this same attitude. The predominant religion in is Catholicism. Common perceptions of Muslims are based on preconceived notions handed down from one generation to the next. Most of these preconceptions are quite offensive and express false notions about the culture and religion of Muslims.

When I was young I used to see Muslims selling in the market-place. I did not interact with them. I just listened to the offensive comments usually used to describe them. At the same time, I also learned early on in school that they pray five times a day. I could not reconcile these two opposing views of Muslims then.

Before leaving for Pakistan, I was fortunate enough to get to know some Meranao Muslims here in Mindanao. Most Christians only know them as ‘Muslims’ but don’t bother to learn their language or take an interest in their unique culture. I, however, was fortunate enough to be able to live for a while with Asnawi Mangka and his family and parents in Sultan Naga Dimaporo, Lanao del Norte, my first experience living with Muslims. I remember my apprehensions at first. I grew up with the usual Christian perceptions of them as being aggressive, hostile and not to be trusted.

These preconceptions were very far from what I experienced when I finally got to live with them. I joined them in planting crops on their farm, exploring their place, and I was able to join them when they prayed in the mosque. I ate with them and during meals Asnawi asked that we take turns to pray before meals out of respect for each other’s religion. It was a powerful gesture from Asnawi to allow me to pray with them in my own Christian way. I felt I was in a space of freedom and I was accepted for what I was. I also admired Asnawi’s family and neighbours for their hospitality and their willingness to befriend a complete stranger like me. It was not easy at first, but our willingness to engage with each other and my ability to ask questions helped me to overcome some of the long-held prejudices I had. It was very liberating for me.

Louie (far right) drinking tea with friends in Pakistan

The same attitude and openness allowed me to overcome my anxieties when I was in Pakistan. I started exploring the alley-ways in the place where I was assigned. I talked to strangers and gave myself time to familiarise myself with the people by joining them for meals during special occasions, or just spending time in long conversations over a cup of tea. Some became like brothers to me. Although I was constantly bombarded by accounts of negative experiences of Muslims with Christians, my prior memories of the time spent with Asnawi and his family enabled me to realize that one’s religion should not be confused with one’s individual behaviour and cultural practices - which is what tends to happen in Pakistan. It was hard to go against the ghetto mentality that exists among the Christian minority in Pakistan. However, I drew inspiration from the Meranao Muslims that I lived with in Mindanao. Asnawi and his family not only opened their home; they opened their lives and hearts with the warmth of their welcome.

Now I’m back in the Philippines. That experience with Asnawi and his family has contributed to my being able to somehow understand how it is to live as part of a minority in a country where the majority confuse culture with religion. Recently I joined an event called ‘Duyog Ramadan’ where Christians join Muslims in the daily breaking of the Ramadan fast (Iftar). It was very encouraging to see many Christians joining this event in a symbolic gesture of solidarity. Among those who joined were students.

It is very important that we value a celebration that matters to our Muslim neighbors no matter how small a minority they are in the overall population of the Philippines. I am hopeful that by constant openness to engage with people from other faiths, the current indifference and mistrust will diminish and that we will begin to see more objectively that, though we are different, in our innermost being we are very similar. Whether one belongs to the minority or the majority does not matter. What is most needed is our constant openness to engage with people from other faiths, to find the good in them and to appreciate our differences rather than to let them divide us. I am optimistic as I continue on a journey to move farther outside my own ghetto, to a space of freedom from prejudice, because I see a great need for this at a time where sectarian violence is so common and where the tendency to condemn others out of ignorance is so pervasive.

Pakistan National Catholic Youth Camp 2007 Ayubya

Dialogue of Ordinary Life in Pakistan

This article, written when Louie was still in Pakistan, first appeared on the July 2016 issue of The Far East, the magazine of the Columbans in Australia and New Zealand.

Louie with friends in Pakistan

I am assigned to St Joseph’s Parish, in Matli, the Diocese of Hyderabad, Pakistan. The parish has a Christian community that lives close to Hindu and Muslim neighbors. This is a great start for my interest in interreligious dialogue.

One finds many prejudices among the different religious communities. It seems that sensitive issues are often brushed under the rug for fear of an outburst of violence. If buttons are pushed, so to speak, it could lead to an outburst such as what happened in Lahore in 2014 when two churches were bombed. Two men suspected of involvement were beaten and burned to death by an angry mob.

Because of this, we look for opportunities that present themselves in ordinary daily life to share and witness to our faith. Here are two examples.

Saleem and his sons

I got to know Saleem and his sons, Imran and Amir, through Columban Fr Tomás King who is Irish. Many times they have been commissioned to do some carpentry work for the parish church. During my free time, I go to their carpentry shop. We talk mostly about carpentry. I share my thoughts as well. The two sons are very friendly. Through them I have become aware of the traditions and culture of Pakistani Muslims. I also tell them about the Philippines and our culture and traditions. They introduced me to many of their friends. This has helped me grow in confidence in getting to know many Muslims and relating to them.

The author

The man on top of the bus

Once when I travelled to Badin from Matli, the bus broke down so I had to transfer to another bus. As it was peak hour I had no choice but to climb up on the roof of the bus and sit along with many people on their way home from work. I sat comfortably in the center of the roof with a good scenic view of the Sindh plains. Many of my fellow roof passengers were surprised and interested as to why a seemingly ‘Chinese man’ would climb up the roof for half-fare. Anyone from other parts of Asia is usually assumed to be from China.

Louie with friends in Pakistan

Soon enough I got into a conversation and my little knowledge of the Urdu language became very handy. What caught my attention was this young man who wanted to talk to me but was unable because he sat too far away. He noticed the cross on the rosary bracelet that I was wearing. Unable to be heard he pointed to the cross and then he pointed towards the sky. When we reached Badin I asked him if he was a Christian. He was a Muslim. I was stunned by a Muslim associating the cross with God. We introduced ourselves and parted ways with a handshake.

Here in Pakistan dialogue happens in the everyday reality of life. It happens as I walk down a busy alley, as I respond to the greetings of my Muslim and Hindu neighbors, as I go through different stores and am offered chai (Pakistani tea) as a sign of hospitality. In the school I get to witness friendship between children of different religions. It comes about when I go to a barbershop and engage in casual conversation when being asked all sorts of questions or when I travel on a bus where I get to stand beside a complete stranger and engage in conversation on the harsh but sometimes funny realities of Pakistani life.

With more friends in Pakistan

Meeting Mother Teresa

By Fr Michael Mohally

Mother Teresa with Fr Michael Mohally

Blessed Mother Teresa will be canonized by Pope Francis on Rome on 4 September. We are re-publishing this article by Columban Fr Michael Mohally who met the saint a number of times. We first printed it in the September-October 2003 issue of Misyon. Fr Mohally has spent most of his life as a priest working with Columban seminarians, in Ireland and the Philippines. He is now based in the Columban central house in Manila.

Logo for Canonization [Wikipedia]

The first time I was to have met Mother Teresa was in Hong Kong. I was asked to bring a package to her there from where she was to accompany Sisters into China to set up the first foundation of the Missionaries of Charity there. When I got to the convent I was told that the China foundation was on ‘hold’. Newspapers had got hold of the story and said that she was going there as the representative of the Pope. Rather than wait around, Mother Teresa had gone to Hanoi to set up a new foundation there.

One evening back home in Manila I received a phone call from the Missionaries of Charity asking if I would preach at the community Mass the following morning. Mother Teresa had just arrived on a visit to the Philippines and was tired after her long journey. They were not sure if she’d be at the early Mass but since all the Sisters in the Manila area would be there, it would be a very special community celebration. I accepted the invitation very reluctantly. I was in awe of Mother Teresa and her reputation as a rather unique person. I discovered that the principal celebrant wouldn’t preach because of his awe for her.

I arrived the following morning and entered the oratory from the rear. The senior Sisters sat at the rear and novices and juniors at the front. A quick glance told me Mother Teresa wasn’t with the seniors so I gave a sigh of relief – she must be having a sleep after her long journey.

We began the Mass and I preached. In my homily I imitated the way a little baby kicks a blanket and holds on to one’s finger and won’t let go. A child finds his identity in what he ‘owns.’ I was aware that one ‘novice’ was really enjoying what I was saying. I was encouraged that the point I was making was being understood. I focused on the ‘novice’ and suddenly recognized the face. It was Mother Teresa. There she was sitting amongst her novices with this winning smile on her face. She seemed tiny to me.

I mentioned in my homily what had transpired between her and Jesus on a train journey to Darjeeling many years before when Mother Teresa was still a Loreto Sister teaching in an exclusive girls’ school. Jesus had told her that the thirst for love, acceptance and respect in the hearts of the poor was His thirst and could be their experience also asked for it. Mother Teresa nodded vigorously in agreement.

Missionaries of Charity [Wikipedia]

After Mass we spoke a little about our not meeting in Hong Kong. I recall her telling me how she had insisted with the Chinese authorities that the Sisters should wear their habit and she mentioned particularly the blue band around the sari, as she wanted it as a symbolic reminder that Our Lady was their protector.

Later that morning as the crowds gathered around for her blessing, she was distributing Miraculous Medals. I was standing some distance away from her and she beckoned to me to come over. With that smile and gentle laughter she said, ‘Father, I must tell you about these medals.’

She was once in Lourdes giving out some medals when a man approached her asking if he could help. She said that what she needed now was more medals. He promised there and then to keep her supplied with a few thousand medals each month. And then she said, ‘You know, Father, they arrive every month just as I am about to run out of them.’

Miraculous Medal [Wikipedia]

I noticed a Middle Eastern couple in the crowd that morning. Their clothing spoke of wealth. I arranged that they be photographed with her. Later I discovered the man was very wealthy and had suffered a heart attack. He reflected on life and his accumulation of wealth, wondered with whom he could share this and had become a sponsor of the Missionaries of Charity. The feeling I had was that he and his wife had flown to the Philippines just to see and be near her.

Reflecting on the few occasions I met her, I would have to say it was her humanity that touched me. She was just a small, chatty old lady with a smile and a gentle sense of humor. She seemed to wear the same worn sandals all the time. She was the personification of her own saying, ‘Peace begins with a smile.’

Plaque of Mother Teresa, Wenceslas Square, Olomouc, Czech Republic [ Wikipedia]

A little child holds on to things to find its identity. ‘This is mine, that is mine’ is what gives it its sense of identity. Our journey through life is meant to lead us to our letting go of things that we think give us identity – status, wealth, degrees or whatever – and discover that it is God’s creative love that gives each of us our true identity.

Mother Teresa understood the story of the little baby. She understood the struggle of letting go and could laugh at it. What kind of sandals she wore did not really matter. She had grown to true Christian adulthood.

Mother Teresa speaking

Our Hideaway

When Church Means Home

By Fr Kurt Zion Pala

Father Kurt is from Iligan City, Lanao del Norte, and was ordained priest in November 2015. He spent two years in Fiji on First Mission Assignment while still a seminarian and a year in Malate Parish, Manila, first as deacon and then as priest. He is currently based in Cagayan de Oro involved in vocations work and mission promotion. He will be taking up an assignment in Myanmar early in 2017. You will find links to previous articles by Father Kurt here.

Father Kurt with altar servers in Malate Church, Manila

Just after I had celebrated Mass in Our Lady of Remedies Church, Malate, Manila, an altar server came up to me and told me that a youth who had decided to leave home wanted to speak to me. I saw a bag in the guard house and I got nervous thinking the story must really be true. I knew the boy in question and when I found him his eyes were red from crying. So I invited him to one of the counseling/confession rooms in the convento. He sat down and started to sob.

After an argument with his mother she told him to leave the house unless he stopped being an altar server. He explained that he had done everything his mother had told him to do but could not leave the church or stop being an altar server. He said, ‘Ang simbahan po para sa akin ay tahanan hindi tulad sa bahay’ (‘The church is like a home to me, unlike the house I live in’). He felt at home and free to be himself in the church. I tried my best to calm him down and asked him to go back home. After a little more convincing he told me he would.

Father Kurt on an outing with young people from Malate

After my ordination as a deacon in May 2015 I joined the parish team in Malate Parish. I started to assist one of the priests in the parish youth ministry and later on took over from him. Building on what had been started and organized, we continued to conduct monthly general assemblies for the youth and faith-sharing sessions twice a month.

Most of the young people involved come from difficult family situations and many of them consider Malate Church their home. One girl shared how her mother was addicted to drugs, taking them to help her keep up with work, but leaving her siblings to her to care of. Another shared that she found herself alone because her parents, now separated and with new families, had left her with her maternal grandmother. She envied her friends with families to call their own. A boy told me that his mother was angry at him because he reminded her of his father who had left her. His mother had a family now and introduced him to his step-brothers as a cousin. A 14-year-old girl shared that she went home late, drunk but pretending to be sick. Her mother continued to look after her probably knowing that she was not sick at all but drunk. The girl shared that she continued to be angry at her parents, but not knowing why. There is so much hurt and pain in these stories.

A ‘snowstorm’ in the tropics?

But there is hope. Knowing that the parish and the Church is there for them, many ‘come home’ to the Church to be nourished – to feel accepted and needed. To see them laugh and enjoy being who they are is really heart-warming and life-giving. People notice that the young people are alive. The church is alive.

Working with the youth in Malate has strengthened my conviction in the words of Pope Francis who said in one of his interviews, ‘This Church with which we should be thinking is the home of all, not a small chapel that can hold only a small group of selected people. We must not reduce the bosom of the universal church to a nest protecting our mediocrity.’

The church is a home particularly to vulnerable groups of people like many of our youth looking for the attention and affection often lacking or missing in their family life. Most of them just want to be listened to and to feel they belong and are needed. The parish has been providing opportunities for them to take on responsibilities and to show their talents.

Being ‘grounded in reality’

In the final month of my stay in Malate the young people I had been working with held a ‘surprise farewell’ for me. And it really was a surprise. As they shared one after the other, I could not help but cry a lot inside and held back my tears. But a few fell, not tears of sadness but of joy listening to my young friends. I often wondered how I was able to survive a year with these crazy, beautiful ‘inside-out’ young persons. They called me by so many different names from ‘Kuya’, ‘Older brother’, to ‘Pads’, short for ‘Father’, to names only they could understand. I learned to speak their lingo and listened to their stories.

My two years in Fiji as a missionary, where I spent much time with young people, and now working with Filipino young people, have been an inspiring, learning, at times disheartening, but mostly joyful, challenging and fulfilling experience for me. Thank you! You all taught me that it is okay to be me.

‘God calls us to be faithful, not successful’, as Antonio Luis Cardinal Tagle, Archbishop of Manila, said at the closing of a youth program, quoting Mother Teresa of Kolkata. True, today young people are trained to be successful in life, to find their value in terms of how they look by the standards of the world or in terms of accomplishments measured in awards and grades. At the Third Philippine Conference on the New Evangelization Cardinal Tagle commented that we are trained to be problem-solvers. We are anxious to find solutions to everything because we make everything a problem. He suggested that instead of seeing everything as a problem we should treat them as dilemmas. Life is a dilemma – a reality we live with, not a problem to be solved. In turn we are called to be faithful, not successful problem-solvers.

For the LORD takes delight in his people, honors the poor with victory (Psalm 149:4)

Young people are not problems to be solved, not mere objects of the Church. They are the Church, too. And when young people consider the Church home, I think we have truly become the Church Jesus intended us to be – a home for every one. A comment from a young person that continues to stick with me is that ‘God does not always give what we want but God always gives what we need’. And I believe the Church is God’s response to our need. That comment of the young boy who said, ‘Ang simbahan po para sa akin ay tahanan hindi tulad sa bahay’, ‘The church is like a home for me, unlike the house I live in’, is a reminder to us adults to welcome every young person as Jesus welcomed every child who came to Him, a reminder for us to be a home to everyone.

Never give up on our young people.

Our Lady of Remedies, Malate Church

Peace By Peace

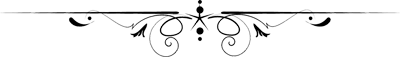

St James the Less, El Greco, 1610-14

Museo de El Greco, Toledo, Spain [Web Gallery of Art]

Instead, the wisdom which comes from above is pure and peace-loving. Persons with this wisdom show understanding and listen to advice; they are full of compassion and good works; they are impartial and sincere. Peacemakers who sow peace reap a harvest of justice.

– James 3:17-18 (Christian Community Bible)

San Pio da Pietrelcina (Padre Pio) celebrating Mass

The Spirit of God is a spirit of peace. Even in the most serious faults He makes us feel a sorrow that is tranquil, humble, and confident. This is precisely because of His mercy.

– St Padre Pio, Capuchin Friar and Mystic (1887 – 1968)

I do not want the peace which passeth understanding, I want the understanding which bringeth peace.

– Helen Keller

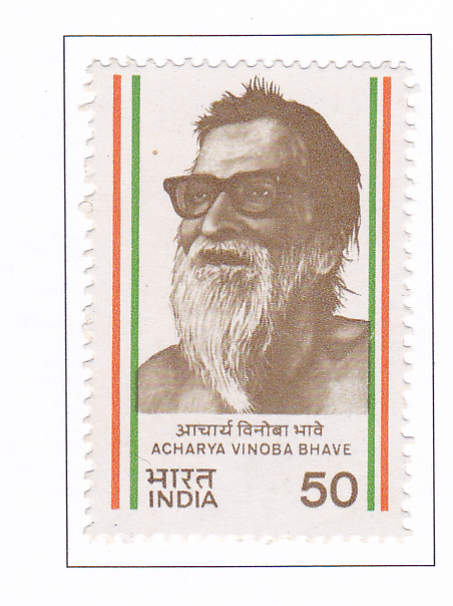

All revolutions are spiritual at the source.

All my activities have the sole purpose of achieving a union of hearts.

– Vinoba Bhave, Apostle of Nonviolence (1895 – 1982)

First recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award, for Community Leadership, in 1958.

We realise the importance of light when we see darkness. We realise the importance of our voice when we are silenced.

– Malala Yousafzai’s speech at the Youth Takeover of the United Nations

We live by faith. We can be so used to living according to our faith that we can forget that faith is God’s gift to us, just as we often forget that our own natural lives are ours only by God’s free gift. We can believe, trust and obey God and submit ourselves totally to Christ as our Lord and Savior only by the grace of God.

– Faith is God’s Gift. Faith and New Evangelization, 2 February 2013

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.

The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some 50 miles of concrete pavement.

We pay for a single fighter with a half million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. This is, I repeat, the best way of life to be found on the road the world has been taking.

This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.

– Dwight D. Eisenhower, Presidential Address, 16 April 1953

Pulong ng Editor

A Columban Centennial on 10 October

Frs Edward Galvin, John Blowick, Owen McPolin, China 1920

Fr McPolin led the first group of Columbans to Korea in 1933

One hundred years ago on 10 October the Bishops of Ireland gave their blessing to a new venture known as the Maynooth Mission to China. On 29 June 1918 this venture became the Society of St Columban, in the Diocese of Galway, Ireland. The Missionary Society of St Columban, as it is now known, is already preparing to celebrate its Centennial in 2018.

As your editor sees it, 29 June 1918 was the date when the Society was ‘baptized’. It had been ‘conceived’ in China between 1912 and 1916 when Fr Edward Galvin, ordained in 1909, and three or four other Irish diocesan priests working there saw the need for a mission of the Irish Church to China. It was ‘born’ on 10 October 1916 when the Irish bishops, approached by Fr Galvin and Fr John Blowick, ordained in 1913 and already a young professor at St Patrick’s, Maynooth, the national seminary for Ireland, gave their assent to the ‘Maynooth Mission to China’.

In Easter Week 1916 an uprising against British rule in Ireland took place, mainly in Dublin. The country was still part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Irish regiments of the British Army were fighting in the Great War (1914-18), mainly in Belgium and France. Nearly 30,000 of them died during that conflict. There was widespread extreme poverty in Ireland, particularly in the cities. 1916 did not seem a good time to start such a foolhardy venture as sending Irish priests to preach the Gospel in China, a country very few Irish people knew anything about.

But the Irish bishops said ‘Yes’ to the Maynooth Mission to China. And the people supported it, as they have continued to do down the years. Fr Blowick once said that the pennies of the poor were more important than the pounds of the rich. But he welcomed both.

The vision of a mission of the Irish Church to China broadened to a more international one. After the Society of St Columban was set up – all the founding members were Irish diocesan priests and seminarians – priests were sent to the USA and Australia to establish roots there, especially among the large Irish diaspora. Irish-American Archbishop Jeremiah Harty of Omaha, Nebraska, USA, invited the Society to set up shop there. He had been Archbishop of Manila (1903 – 1916), the first non-Spaniard to hold that position.

The first group of Columban priests went to China in 1920.

In response to an urgent appeal by Archbishop Harty’s successor in Manila, Irishman Michael O’Doherty, the Columbans took over Malate Parish in 1929. By the 1970s around 260 Columbans were working in Luzon, Negros and Mindanao. All the parishes they staffed and opened, except Malate, are now served by diocesan priests and the number of Columban priests in the Philippines is around 30.

Over the years the Columbans have taken on missions in Korea, Burma (now Myanmar), Japan, Chile, Peru, Fiji, Pakistan and Taiwan. They have had missions also in Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Guatemala and Jamaica.

Most of the younger Columban priests are from countries the older men had gone to from the West. Fr Leo Distor, the first Filipino Columban parish priest of Malate, is a symbol of the changing face of the Society. After serving in Korea he spent many years in Chicago and in Quezon City in the formation of future Columban priests from Asia, the Pacific and South America.

This year there are Columban seminarians from China, Fiji, Myanmar, the Philippines and Tonga in the formation house in Cubao, Quezon City and on the two-year First Mission Assignment (FMA) overseas. The Filipinos include Louie Ybañez of Holy Rosary Parish, Agusan, Cagayan de Oro City, a former Columban parish, recently returned from his FMA in Pakistan, and Erl Dylan Tabaco from the same parish as Louie and Emmanuel Trocino from Pulupandan, Negros Occidental, back from FMA in Peru.

The young Fr Edward Galvin (1882-1956), later Bishop of Nancheng, China, and the young Fr John Blowick (1888-1972), not to mention the Irish bishops in 1916, could not have foreseen how the Maynooth Mission to China would evolve from being a purely Irish venture into the international Society it is today with Priest Associates from dioceses in Ireland, Korea, Myanmar and the Solomon Islands, and Lay Missionaries from Chile, Fiji, Ireland, Korea, Philippines and Tonga currently involved in its mission.

Thank God for the birth of the Maynooth Mission to China on 10 October 1916.

The God of Surprises: Pilar and CLM Beginnings

By Fr Michael Martin

This is a slightly edited extract from the book Walking in Their Light, written by Columban Fr Michael Martin on the occasion of the Golden Jubilee of his ordination to the priesthood last year, 2015. September 2016 marks the end of a year of events for the Silver Jubilee of the Columban Lay Missionaries (CLM).

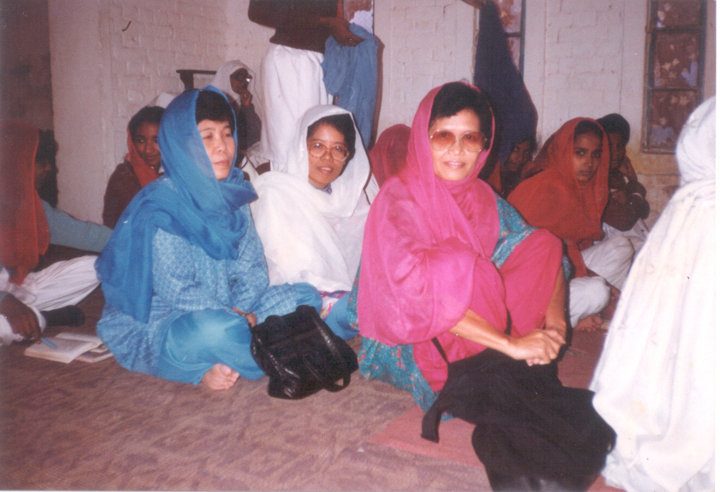

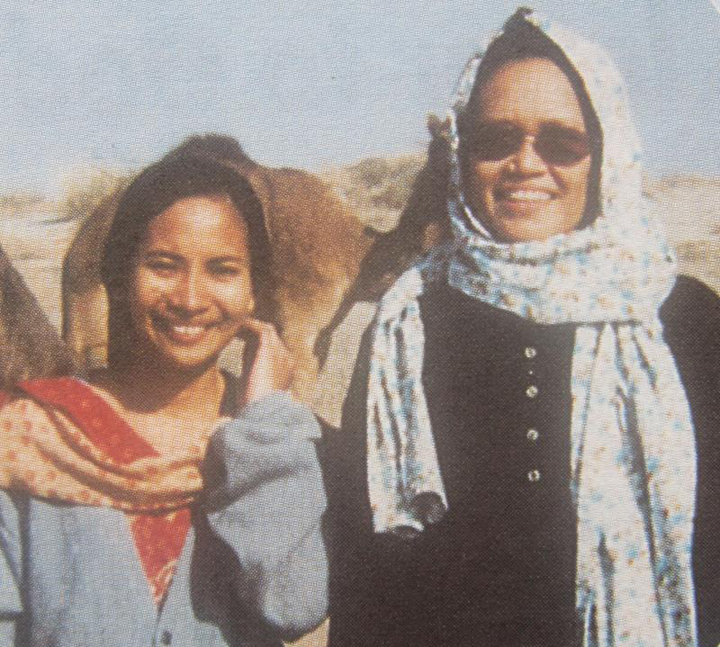

L to R: Emma Pabera, Gloria Canama and Pilar Tilos

Three Filipinas, Emma Pabera, from Candoni, Pilar Tilos from Hinoba-an, both in Negros Occidental and the Diocese of Kabankalan, and Gloria Canama from Tangub City, Misamis Occidental, Archdiocese of Ozamiz, resigned from their work in 1990 and came together for an eight-month team-building program to prepare themselves to go as Columban Lay Missionaries to Pakistan. The three were hard-working and experienced teachers, all from families really close to the Columbans, and all exceptionally enthused about that missionary way of being Church, Pilar Tilos, who had coordinated physical education, and assisted in promoting sports, dance, and music in the public elementary schools of Hinoba-an, the southernmost municipality in Negros Occidental, had long felt called to mission. She applied, was accepted, and joined the first Columban Philippine Lay Mission Team, named ‘RP1’. ‘Larps’ - her nickname - was a great mimic and the life and soul of many a party and parish activity.

The team spent three months in a Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) course then available in a Presbyterian university hospital. As strong, determined, and sensitive women faced with the pain of the sick and the dying, they struggled in learning how to listen better and be gently with one another. They spent an even longer period in a lay leadership training program followed by an immersion in communities of empowered laity. Among the three, Pilar was the extrovert, the athlete, the dancer. They shared and prayed on the Word and the constants in mission, aware that the context, Pakistan, would be bewildering, but that the people would be welcoming.

In Pilar’s sending ceremony, she resembled a bride ready for the wedding, and not afraid of embracing the world. This time she was saying goodbye to her homeland, to her parish community, and to her group, ‘The Pearly Shells’, who had sung and danced and entertained together since they were children.

In the Hinoba-an parish community she was well known for standing up against the abuses of martial law (1971 – 1982 officially). Indeed, she assisted her co-teachers in another town when their supervisor stole part of their salaries. In fact, she successfully stopped this person from getting a retirement pension until all the victims were reimbursed.

It was my privilege to assist the three get ready for a new kind of work, a new kind of mission in which they would be pioneers. Columbans in the Philippines were searching for ways to assist partner churches to become more missionary, and the prospect of a team of three talented, educated Filipinas immersing themselves among women in a predominantly Muslim country was challenging. In order to reach out to the illiterate, Pilar and Emma and Gloria identified their need for special training in adult literacy, a course which served them well: they taught Christian women to read their scriptures, and they helped Muslim women find the face of God in their Qur’an.

Some Christian communities of impoverished people were alive and active in the Lahore area in north Pakistan, but they were small, and often isolated, even in the city. The clergy, including the Columbans, served them as well as they could, but the women members were even more marginalized. Female missionaries were a special blessing. They empowered the people especially through song and dance, livelihood-generating skills, awareness-raising, and committed accompaniment.

But God is a God of surprises, and the disciple is not above the Master, who himself prayed: ‘Not my will, but yours be done’.

Auring Luceño (Pagadian City) and Pilar Tilos in Pakistan

An entry in the Columban book of obituaries, Those Who Journeyed With Us, reads:

‘PILAR TILOS . . . baptized by a Columban, Pilar was a member of the 1990 Lay Mission Group, the first R.P. group to be assigned to Pakistan. Hard-working and full of life and humour, Pilar died in her sleep at St Columban’s, Lahore, on 4 January 1996 and is buried in Lahore.’

We treasure a striking, inspiring story of her farewell, written by Fr Pat McInerney, an Australian, the then Columban Co-ordinator in Pakistan:

‘We all gathered in the chapel around the body of Pilar for a Eucharist. All the Columban group in Lahore was present, and many friends and supporters from the Filipino community, the Sisters, parishioners, all united in shared shock and grief…

‘We prayed for Larps. We thanked her for her life. We thanked her for her faith. We thanked her for her laughter. We thanked her for her commitment to the poor. We thanked her for her simplicity. We thanked her for her fun. And in tears we told her we would miss her. The openness of that public sharing was deeply moving to all who were present, as we realized just how deeply and in how many different ways Pilar had touched the lives of us all. It was truly Eucharist, thanksgiving for the life and death of a friend.’

Pilar had served in Pakistan for five years before the Lord called her home. She had inspired people, and now her smile lives on in Hinoba-an, in Lahore, and in Columban missionary history and folklore. May she rest in peace.

CLMs Annie Budiongan (Loboc, Bohol), Auring Luceño and Gloria Canama at Pilar’s grave

[Editor’s note: The first 19 groups of CLMs from the Philippines are known as RP1, RP2, etc. Since the Government switched to using ‘PH’ instead of ‘RP’ as an international code for the country they have been known as PH20, PH21 etc.]

St Peter’s Catholic Church, Karachi

To Search is To Find

The Angelus, Jean-François Millet, 1859-60

Musée d'Orsay, Paris [Web Gallery of Art]

I have received many messages on Facebook, through texts and emails about luck, eg, ‘Please pass this on to 10 persons and after three days you will receive luck’ or, especially on FB, ‘If you really believe, pass this on to others’ or ‘If you believe, press Amen’ etc.

Thank you for your question. What you ask about are high-tech versions of a very old phenomenon: chain-letters. I get quite a few but never pass them on. Most are an expression of good will and concern from friends, accompanied by prayers. That's good and I usually thank my friends for remembering me.

Just today I received an FB message, a photo with this message: ‘One day you’ll be just a memory for some people. Do your best to be a good one. Type ‘Yes” if you agree.’

There’s nothing wrong with the first part of this. But ‘Type “yes” if you agree’ is a mild form of ‘blackmail’, laying a guilt trip on the receiver. The sender clearly has only good intentions but why should I as a receiver be asked to type ‘Yes’ and perhaps be made feel a little guilty if I don’t?

Many of the FB messages and emails of this kind that I receive are connected with saints, eg, St Thérèse of Lisieux, or with the Blessed Mother. They sometimes say, things like, 'Send this to ten people in ten minutes and you will receive a special blessing within two days,' as in your question. This is a distortion of our Christian faith, though well-meant. We cannot earn God's love. The First Letter of St John says, ‘In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins’ (1 Jn 4:10). We're saved by God's unconditional love, pure gift, shown in Jesus dying on the cross for us. We're not saved by sending emails, text or FB messages to our friends! I have a friend in the USA who kept sending me this kind of email. I know her to be a devout Catholic. However, one day an email arrived from one of those on her email list asking her gently not to send any more of that kind. I then emailed her to tell her that I thought the same way as her friend. She understood.

I wouldn't go so far as to say that the Devil is behind all of this, rather a misunderstanding of our faith and of God's love that is beyond what we can imagine. I think it's wonderful to know that even if I'm the world's greatest sinner God still loves me. But once I have even a small idea of the fact that God loves me unconditionally, then I want to do God's will. We find the same thing with people who love us. We want to return their love, di ba?

A more harmful variation of this is with some 'healers' who tell poor people such things as 'offer up a chicken/pig/whatever and your child will get well.' Or 'say some huge number of prayers. If you don't, something will happen to you.' Quite possibly the Devil is a little more involved with that, though the 'healer' might not be aware of that. It certainly doesn't come from God.

Our prayers cannot 'force' God. Real prayer acknowledges God as the source of everything. The model for all prayer is the 'Our Father,' taught by Jesus, God become Man. It's basically a prayer to submit ourselves to God's will.

On the other hand, modern technology enables us to share lots of good news with our friends, eg, links to uplifting stories. We can also send links to stories about the difficulties Christians and others may be face in a war-torn world. This can be a way of sharing the Gospel, sometimes challenging us. But we can also be overwhelmed by a deluge of such messages, in which case we can simply delete them, which doesn’t in any way hurt the sender.

Blessed Mother Teresa (from 4 September ‘St Teresa of Kolkata’)

Christ says: I know you through and through – I know everything about you. The very hairs of your head I have numbered. Nothing in your life is unimportant to me, I have followed you through the years, and I have always loved you – even in your wanderings. I know every one of your problems. I know your need and your worries. And yes, I know all your sins. But I tell you again that I love you – not for what you have or haven’t done – I love you for you, for the beauty and dignity my Father gave you by creating you in his own image. [Source: The Living Spirit]

Blessed Mother Teresa on Prayer

Youth, Reconciliation and Pilgrimage

By Fr G. Chris Saenz, Chile, ‘00

The author is from Omaha, Nebraska, USA, and is a frequent contributor to Columban publications. He spent some time in the Philippines during his formation and was ordained in 2000. He is based in Chile.

Fr Chris Saenz with young pilgrims

‘Father, I am angry that my parents are divorcing.’ This could be an example of a young person’s confession. I am often struck by the honesty and profoundness of what young people share. It highlights for me what the sacrament of reconciliation means - a true desire to seek God’s saving grace in a situation that one would like to leave behind.

There is much discussion today about the sacrament of reconciliation (‘confession’, ‘penance’) as the ‘lost’, ‘underused’ sacrament that the younger generation ignores. In mission I have discovered that this isn’t true. I believe it is a frequently used sacrament by the youth, given the proper conditions.

Confession during the pilgrimage

Having ministered to people in four different continents, I truly believe thus: The older generation utilize the sacrament more frequently but understand it the least. The younger generation utilizes the sacrament less frequently but understands it better. There are exceptions but, in general, this has been my experience.

The older generation’s experience can be described as ‘confessing the sins of the other’. The penitent enters the sacrament worried about a situation but generally turns the worry into a complaint about what the other ‘should do’ or ‘isn’t doing’. Often the guilty ‘other’ is a son or daughter. When this occurs I will stop the person and emphasize that the sacrament of reconciliation is about one’s own sins, not about another’s. Often the response is: ‘Oh, okay, Father. Well, I don’t have anything else’. Or, there is a quick mechanical recitation of their misdeeds: bad thoughts, profanity, not fulfilling the Sunday obligation, etc. I believe the old-style Catholic formation taught a mechanical ‘check list’ of sins to appease an angry, vengeful God. It did not invite a deep reflection about their relationship with God. Dialogue and discussion of ‘feelings and emotions’ were out of the question.

Celebrating the Sacrament of Reconciliation/Confession/Penance

Meanwhile, the younger generation’s experience has been very akin to the opening quotation of this article. They focus on their emotions and feelings about a particular situation. They seek a dialogue with the God of forgiveness and compassion to better understand what they are feeling and living. The younger generation keep the focus on themselves and very rarely enter into the sins of the other. The opening quote reflects this: the focus is the person’s anger, not the divorce of the parents. A person seeks guidance on how to handle his or her anger in a situation that deeply affects the family. For me, that is a true moment of reconciliation.

So what compels a young person’s desire to seek the sacrament of reconciliation? And, when? The traditional style of providing the sacrament one hour a week in a box in a church does not attract young people today. That model might have served a previous generation. Young people seek an external expression of the faith linked to the sacrament of reconciliation. It is here that I discovered in mission the power of pilgrimage.

‘Peregrinos pro Christo’ – Pilgrims for Christ

The early Church linked reconciliation to pilgrimage. The penitent, after causing harm to the community, was sent on a pilgrimage away from the community. This physical distance from the problem gave the penitent time to contemplate and the community to heal. The physical struggles of the pilgrimage – a long journey, harsh weather conditions - reflected the inner spiritual struggle. It was not just a spiritual renewal but a physical one as well. Centuries later, the tradition of ‘box’ confessions came in and the physicality was lost. I believe that the young people unconsciously seek a return to the early Church’s tradition of reconciliation and pilgrimage.

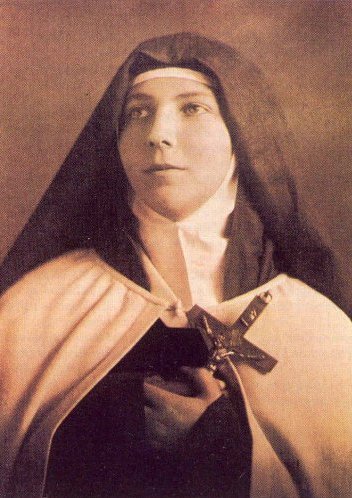

Santa Teresa de Los Andes

(13 July 1900 – 12 April 1920) [Wikipedia]

St Teresa of Jesus of Los Andes is the first Chilean to be declared a Saint. She is the first Discalced Carmelite Nun to become a Saint outside the boundaries of Europe and the fourth Saint Teresa in Carmel together with Saints Teresa of Avila, of Florence and of Lisieux.

In Chile, the largest youth pilgrimage is to the Sanctuary of Santa Teresita de Los Andes. About 70,000 people attend, mostly young people. They arrive early on a Saturday morning in October from different parts of Chile. They began the 27kms walk to the Sanctuary. The climate is semi-arid, the sun is hot and the mountainous terrain rugged. During the walk there are stations where social events are organized like music concerts and dynamic presentations. Some stations provide group prayer like the rosary but the most utilized stations are those providing the sacrament of reconciliation. Priests are sitting alongside the road attending to the pilgrims as they walk by. A priest can spend six hours confessing non-stop. Eventually, the pilgrims arrive at the sanctuary in the afternoon feeling physically tired but spiritually renewed. There they participate in the closing Mass. After the Mass many of the groups share a meal together before going home.

Santuario de Santa Teresa de Los Andes (Santuario de Auco)

The most popular and largest pilgrimage is to the Sanctuary of Lo Vasquez dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It is estimated that nearly one million people travel on foot to the sanctuary on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, 8 December. It is 75kms from Santiago on Route 68. On that day the 115kms of Route 68 between Santiago and Valparaiso are closed. Usually the summer sun is extremely hot and the pilgrims walk all day. At the sanctuary the sacrament of reconciliation is provided and priests spend the whole day hearing confessions. Many young people participate in the pilgrimage. Many go to confession.

The crypt at the Santuario where Sta Teresita is buried

When I worked in Puerto Saavedra in the south of Chile, the local pilgrimage was to San Sebastian on 20 January. A few thousand participate in the event. Pilgrims often walk from the rural areas or from the neighboring town of Carahue, 33kms from Puerto Saavedra. Many young people participate and begin walking at night to arrive for Mass at 6am. They stay after Mass to pray, say the rosary, and confess. Priests are in the church all morning. The youth wait to attend the main Mass at 11am. After this the image of San Sebastian is carried in procession around the town, the pilgrims singing. When it is placed back in the church, many of the pilgrims go to the beach, have a meal and relax. Later they go home feeling physically, spiritually and emotionally satisfied.

This desire of the youth to participate in pilgrimages highlights that the sacrament of reconciliation is not ‘out of use’ among today’s young generation. They are crying for more than a ‘cold box’ to confess in. They seek an integrated, holistic experience of reconciliation linked to pilgrimage.

A taste of the pilgrimage