September-October 2003

A Life With Criminals

By Paulo Baleinakorodawa

Paulo Baleinakorodawa worked for three years in the Philippines as a Columban lay missionary. He is now coordinator of Columban Companions in Mission in his native Fiji.

People used to ask me in the Philippines why I hung around so much with criminals. It wasn’t easy to answer. Perhaps it was because of my love and compassion for them. But deep within me was a burning passion to help them know and feel that, despite their wrongdoing, God loved them in the same way He loved those in free society. Here the strength of the message of the Cross became real – God loves and accepts each one of us with no strings attached.

As a Columban Lay Missionary from Fiji I got involved with the prisoners in Olongapo District Jail soon after being assigned to Immaculate Conception Parish, Barretto, Olongapo, in mid-1997. The jail had about 250 inmates. About eight percent were serving sentences of three years and below while the rest were detained pending trials. It was rather shocking to know that because of the snail-paced judicial system many had been languishing in this situation for three years or more.

I used to spend six days a week in the jail. This involved coordinating and providing Bible services, prayer meetings and such, and arranging for the celebration of the sacraments. I also coordinated religious instruction, seminars and retreats for the formation of the prisoners. In addition, I coordinated legal assistance, literacy programs and basic guidance and counseling sessions.

The ministry tremendously widened my view of Mission. As I understand it now, it enables people to experience God in Jesus in their own ways. To put this in my mission context then, it was enabling prisoners to experience God in Jesus as prisoners. It was journeying with them in their search for God and Life in ways that were truly theirs, no matter what their circumstances in life were. These ways allowed them to see, taste, smell, hear and feel God. Through this they could claim they were at home with God, with the whole of humanity and creation. They could make their own the beautiful opening words of the First Letter of St. John, This is what we proclaim to you: what was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked upon and our hands have touched – we speak of the word of life.

It is a real challenge for a missionary to try to enable people to make this experience a reality in their lives. For me as a lay missionary, walking daily with prisoners in their difficult journey through life, it was even more challenging. I was relating to people with no public face, the voiceless, the poorest of the poor and the outcasts of society. Through my interaction with them I came to realize the great need to be a voice for them. Given their circumstances, prisoners have a very low sense of self-worth, if any at all. How could I show God’s compassionate love for them in the wretched state they were in? Because of negative attitudes in society towards them, they have often been deprived of their human dignity. In many cases, because of their confinement, they have been stripped of their basic human rights. Many are innocent and languishing behind bars because of an unjust legal system. Many times there is little that can be done, but just being there for them and to have the time to listen to the cry of their souls is for me an opening where they can experience the love of God flourishing in their lives.

I was in this ministry for almost three years. At times I wonder if my presence had an impact on the lives of the prisoners. But deep inside I can feel a great sense of gratitude and satisfaction that at least I was trying to do all I could. I know and believe that God did the rest.

This for me is Mission, because this is not just my mission but God’s mission. I’m called as a missionary to become a visible sign of the invisible grace of God, and to awaken people to the mystery of the Divine in their lives so that they will come to experience God in Jesus in their very being!

And Far Away…Some Children Smile

By Fr Anthony T Pizarro CICM

No, this is not a publicity campaign using the ever-admired slogan on the bumper stickers of the one million or so tricycles that the city of Tuguegarao is known for. This is the story of how my belovedalma mater, St Louis University of Tuguegarao, has come to the aid of some people here in Senegal, of how SLU has extended its social awareness across the world to the people of this west African country.

Giving what I have received

Every October the mission month campaign sees the whole of SLU in a frenzy of mission-awareness and solidarity activities. There are conferences animated by Pinoy CICM missionaries on vacation; programs highlighting the uniqueness of each country, the differences between them but also the oneness of the peoples of the world; mission-awareness talks; prayer sessions and Masses for the intensifications of missionaries; letter-writing and card-sending to show support for missionaries; and of course, the collection of gifts and money to help the missions. I still remember my college days when the whole SLU community, from kinder to the post-graduate school, administration, faculties and students, would make this month an occasion for showing our concern for and solidarity with people different from us.

The activity I remember most vividly is collecting money. The campus ministry that I headed spearheaded this. As a community member I had my share of humbly shelling out (read: giving, donating, sharing) some of my weekly allowance for the missions. That meant one whole month depriving myself of renting videos and weekend gallivanting and drinking sessions with my collegebarkada. Mission-month then took the idea of sharing concretized in the adage of solidarity: ‘no one is so poor as not to give and no one is so rich as not to accept.’ That was eight years ago but the beautiful tradition of solidarity lives on in my alma mater. It continues with an increased fervor and awareness that it’s only in sharing a bit of what we have that we can help somebody really needy somewhere else in our small planet who is unknown to us.

Here in Senegal the objective is to share in the best possible way what I receive from the proceeds of the mission campaign in SLU. Knowing that what I receive could be the humble sharing of some small kindergarten pupil in Tuguegarao, it is then my task as a steward to let this sharing reach the most needy of the population with whom I work.

Mission in Dakar

My first mission assignment was in Dakar, the capital, a city of four million. We work in the suburban community of Guediawaye. The people here are very poor. There is a very high rate of unemployment caused by a massive exodus from rural areas. All of this causes juvenile delinquency, prostitution, drug addiction and other forms of corruption. In this desert of problems we try to plant some seeds of hope. Education and water are our aims.

Anne is twelve and in Grade Six in a private Catholic school. Her mother, a single parent and our part-time cook, was very sick for three months. Unpaid bills and debts mounted. Anne nearly had to stop her schooling. No way for such a bright and promising girl! With the help of SLU she’s now at least assured of continuing her schooling for two more years.

The same applies to Kine, a very intelligent girl aged 11, whose sickly and jobless father couldn’t make ends meet for his family of eight. She too is assured of two years’ tuition and allowance.

Water of Life

With a CICM confrere I was able to finance the construction of a deep well for the community of Malika. This is a small community of Muslim and Christian settlers from the provinces. As newcomers in the individualistic capital, the people belong to the great majority of the jobless and eternal job seekers. In a desert environment water is a prime commodity. Having no resources of their own, we decided to help them. A Benedictine monk who is a water-diviner helped us to find the underground reserve. With the help of SLU, we bought the materials needed and the people took care of the manual work. How wonderful to see a whole community mobilized for such a project. Fresh and pure water for the whole community!

Unfriendly weather

Next assignment is Podor, a town 500kms north of Dakar, near the border of Mauritania, where the temperature can climb to 45° and drop to 5°. Shortly before our visit very cold northerly winds coupled with out-of-season rains caused massive destruction to the small livestock industry and agriculture of the people. El Niño gave the final blow. The people had to live through aid from abroad while trying painfully and slowly to reconstruct from the debris.

Badji, 46, a Muslim, is the father of five. He came from the south hunting for a job. He found nothing in Dakar and landed here in the north. After finishing a six-month temporary job as a mechanic, he was jobless again. With an indefatigable spirit, he’s the epitome of the Senegalese luck-searcher. No way could he let his family back home die of poverty. The parish lent him the empty lot beside the church. He planned to plant okra and onions, a staple legume in Senegal, but had nothing to start with. With the help I receive from SLU I gave him some capital to finance the labor, fuel for the water pump, seeds, pesticides and some fertilizer. His hard work and fervent prayers were crowned with very productive harvests. After two successful campaigns he’s now financially independent. I plan to extend the same help to some other needy village farmers.

Next is Thomas, 46, an English-speaking Ghanaian. He and his wife came to Podor, leaving their three children behind, to look for work but declared later, ‘Senegal is as poor as my country.’ I knew him to be a very hard worker, a prayerful Catholic and full of wisdom coupled with a good sense of humor. He first ventured into haircutting but because of hard times couldn’t even make enough to pay his electric bills. He started a small poultry project with ten chickens. This did well. He then planned to go ‘big-time,’ which here means raising 100 to 150 chickens! Audacity needs capital. I gave him the needed boost so that he could realize his dream of providing chickens for his village. 45 days later the whole neighborhood came to buy them for the traditional Muslim feast of Korite, the end of Ramadan. Another story of nurturing the innate hope of bearing good fruits for life!

These are but a few examples of what I do to assure the good stewardship of the financial gifts I’ve received from my alma mater. The help from kindergarten pupils to young professionals in USL is channeled into education, community building and livelihood projects here that give life and nourish the hope.

Of course we are present among the people. We pray and witness to international brotherhood. But more than that, we try to be of concrete help to really unfortunate people in our surroundings. For me, that is the mission of the Church – to work and pray for the realization of the Kingdom of peace, justice and love here and now in this small planet of ours. These are but little efforts but nonetheless clearly shows that with solidarity, and the concrete manifestation of it through sharing the little we have, we can ease the burden – help carry the heavy crosses – of people more unfortunate than us. This is our Christian witnessing, that hope may live! This is the tradition of the university community of SLU concretized overseas here in this small country in Africa.

And for the help we receive ‘with love from Tuguegarao’ we say ‘Jerejef’, with many thanks, to your beautiful people!’

Father Joeker

By Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

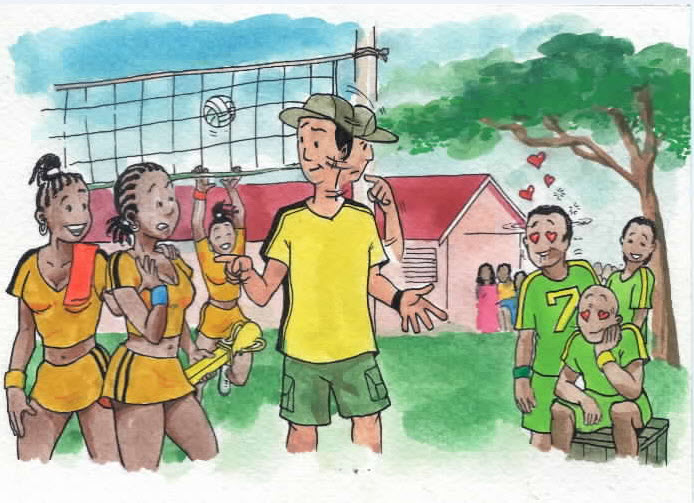

Labang Volleyball

Inimbitahan ng Our Lady of Fatima School and aking mga altar boys na maglaro ng volleyball laban sa kanilang women’s team. Di ako makapaniwala na natalo nila kami. “Ang daya nyo,” sabi ko sa kanila. “Nanalo kayo dahil ginayuma nyo ang aking mga altar boys.” Matinding tumutol ang mga babae, “Aba, hindi ah! Huwag kayong mamimintang, Father. Anong magagawa naming eh nagdasal kami. Ang mga altar boys mo nagdasal ba? Tignang nyo sila o.”

Never ending photo sessions

During our renewal course in Steyl, Holland, we had a pilgrimage to Issum, Kevelaer, Goch, Germany, where we had lots of picture-taking. Everyone had a camera except me and one confrere. So we remained with the group posing for the shots while those with a camera would walk out to take a shot one after the other. After the picture-taking I said, “This is great! This is what’s good about not having your own camera. You are in every shot.”

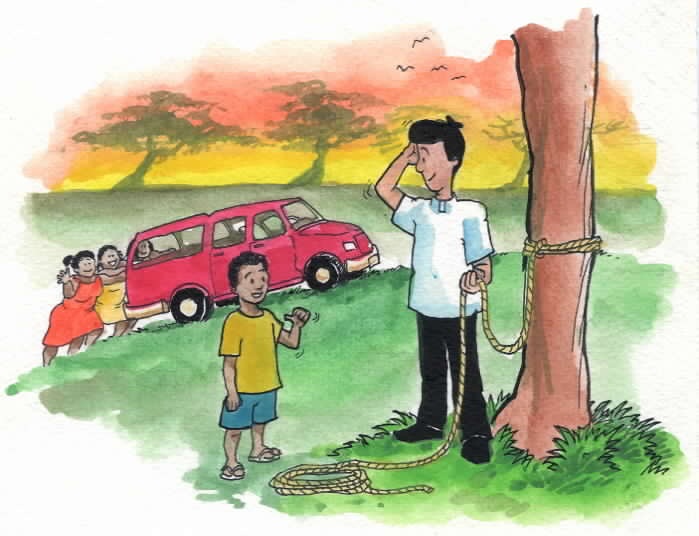

The Amazons

I parked our Toyota double cabin car under the tree on sloping ground but did not put on the handbrake. While inside the convent, I heard women’s voices screaming for help. Ali Jara, my mission boy, ran outside, but instead of helping the three women, he laughed at them until I came to the rescue. Held by such big women, the all-powerful Toyota, pride of Japan, looked utterly helpless.

Gatas ng Kalabaw

Sa aming Renewal Course, ikinukwento ko ito sa aking mga kasama… “Ako ang bunso sa aming magkakapatid. Nang ipinanganak ako, sabi ni Nanay inubos na daw ng mga nakakatanda kong kapatid ang kanyang gatas at walang nang natira para sa akin. Mabuti na lang nasa bukid ang kalabaw namin. Kung hindi baka gatas ng kalabaw ang ipinainom sa akin.”

Life In The Cordillera Of Chile

By Sr Sally Oyzon SSC

Sibaya, 2, 658 meters above sea level, is a four-hour drive over lowland and mountain deserts from the city of Iquique in northern Chile. It is in one of four inland pueblos in which I ministered in the 1990s. A once thriving community, Sibaya is now sparsely populated. The 35 or so families are those with children up to Grade Six and older ones whose adult children have moved away. As in otherpueblos in the Chilean Cordilleras, the people are of Aymara descent.

Due to the interrelatedness of their economic, political and religious history, the people have lost much of their cultural richness. Thanks to the recent interest of culture groups and the Church, they are receiving more attention as a people who, for their cultural survival, have held on with almost stubborn tenacity – ‘Es la costumbre’ – to some customs. Foremost among these are their devotion to Pachamama (Mother Earth), pueblo patron saints, Santo Tomás de Tolentino and La Virgen de la Asunción, and to their ancestors. Feelings about these are deep and admirable to a fault: in some ways take on more of a social rather than religious dimension. At fiestas drinks flow freely. But these devotions kept alive the faith of the people through the years of minimal pastoral care from priests.

Why do I spend time with them?

After participating in some of their celebrations I felt the need to be friends with the people, to understand better and appreciate more who they were, their life, their ways, their aspirations. I also wanted to spot potential Church leaders. What better way of doing this than being with them in their daily setting?

So at 6:30 on the eve of the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes Fr Sean O’Connor, a Columban from New Zealand, left me in Sibaya. This meant some 50 kms extra drive before he would get to Mocha where he would celebrate Mass next day.

Alone in dark nights

Being summer, the sun was still bright. Everyone had assured me that Sibaya was a safe place. But the thought of spending nights alone in a casita, a little room, beside the big 300-year-old church and the cemetery on the hill behind, the nearest houses being on the other side of the church and down the slope of the hill on the front, only the rooftops being visible, gave me a feeling of anxiety – not fear – and of aloneness as I sorted out my provisions and went to fetch water. I hadn’t spent a whole night alone anywhere in all my years.

The adobong manok I’d brought was a boon. It was dark by the time Don Raul, a parishioner, succeeded in making the gas-stove work. I only had to boil water for tea and toast bread over a metal tin for supper. When the generator light came on for one hour at 9:00, those who had dropped by were ready to leave and I was ready for bed.

Life in Sibaya

Next morning I tried to make a reservation for a seat on the truck that twice a week brought in prime commodities and took out vegetables. The passenger spaces were behind the driver but had been reserved for the next week’s trips. But not to worry – vehicles came in and out and the people would be on the lookout for me.

To accomplish what I came for I had to use different approaches. Jerca was with me at the truck owner’s store, on her way to the farm, ‘Farm’ means a parcel, or parcels, of land planted with vegetables, some of fruit trees, alfalfa for a few head of goats, sheep, llamas or cattle or any combination of these. This is mostly for home consumptions and fiestas. Those with more parcels of land sell their extra produce.

We talked about life, mostly theirs, as Jerca, her sister, brother-in-law and nephew pulled alfalfa, harvested beans, carrots and celery, opened and stopped the ditch that watered the plots and fed the animals. After 2:00 we headed for the pueblo where they prepared lunch before going back to the farm to work again until sundown. On the whole the rhythm of life is Sibaya is a shuttling back and forth between kitchen and farm at least twice a day. The life of the people is indeed a life of ‘small is beautiful.’

I called the homes of nursing mothers not yet able for the farm. Conversation, as they washed clothes and bathed their children, was for the most part mundane, but about them – a bit of their history, their cares and struggles, their customs, what touched them most.

While I was chatting with a couple playing with their toddler in the school playground, a small truck parked nearby. They were returning to the city next morning, Wednesday, at 11:00 and I could go with the driver and his assistant. It would cut short my stay but was a sure ride. Next day 11:00 came and went. I waited until 2:00 to find out that they had left the night before!

False hope

But ‘hope springs eternal.’ A government doctor visits Sibaya every Thursday. He comes alone and has a ‘doble dabina’ – front and back seats. Since I was having lunch with a family, I gave the perishable goods I had to a new Bolivian resident. With my camp bed and bag zipped, I went to the medical station. Trying to keep down my excitement at meeting another Filipina again when I’d reach home, my hope for a ride quickly faded when I saw that the doctor had four big men and a lady nurse with him!

I was in a quandary. Out of provisions, I simply had to get to the city. What to do? I then remembered the two policemen on their rounds who greeted the family I had lunch with. They came occasionally to Sibaya. My last chance. But would they still be around? They were, and took me to Juara from where it would be easy to get to Iquique. I learned later that the police often do this kind of service.

We reached Huara at 6:30pm but all passenger vehicles bound for Iquique had already left. The big buses were Santiago-bound. I would have to make a transfer to get to Iquique, not an attractive proposition with my luggage, small and light as it was. I didn’t know anyone in Huara nor was there aconvento in the place.

I heard someone shouting ‘Iquique!!’ It was the driver of a collective, like our ‘FX’ but with ‘natural airconditioning’. He was looking for two more passengers. After a bit of haggling we agreed on the fare. So for the price of a copy of Misyon I did the last hour of my getting-to-know-Sibaya trip in comfort, right to our door.

Martyrs Of Love

By Father Seán Coyle SSC

This article is based mainly on a report sent to the members of the Missionaries of Charity by Sister M Raphael MC, regional superior in Amman, Jordan, in 1998.

Sister Mary Michael MC was born Victoria Espejon in the Philippines on 21 September 1961. Along with Sr M Zelia MC (Pancratia Minj) and Sr M Aletta MC (Albisia Dung Dung), both from India and just a little younger, she was shot dead in the Red Sea port city of Hodeidah, in the south of Yemen, on the morning of 27 July 1998.

Three Deaths in the Street

The three Sisters set off after Morning Prayer and Holy Mass, offered on the death anniversary of Sr Zelia’s mother. At 7:50 am Sr Zelia phoned Sr Aroti in Sana’a, the capital, 225 kms to the northeast, to say she’d phone again from a place ten minutes walk away. She never made that call. Fifty minutes later Sr Aroti received a distressing call from a woman who worked for the Sisters telling her that Sr Zelia and her two companions had been riddled with bullets only three minutes after leaving the convent. She’d heard the machine-gun fire and had run outside to find the three bodies lying in blood.

Sister Aroti called the other houses of the Missionaries of Charity in Yemen and also Father Jose, the parish priest of Hodeidah. He and the police brought the bodies to the nearby hospital. With great respect, the police handed over to Father Jose the basket and bag of the Sisters containing their slippers, umbrellas, money to pay the phone bill, their crucifixes and rosaries. They then went with him to the Sisters’ convent to examine it carefully. They left the house perfectly tidy. The police inspector was struck by the simple way of life and dedication of the Sisters. Later the police handed the keys to the house to Father Jose.

Support from all over

Sr Aroti then phoned Sr Raphael in Amman and Sr Nirmala, Mother Teresa’s successor, in Calcutta, and the national authorities in Yemen. Help came from all sides. The government gave visas immediately to Sisters coming from elsewhere and to Father Sebastian MC in Rome. They also gave one to Bishop Giovanni Bernardo Gremoli OFM Cap, Vicar Apostolic of Arabia, who lives in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. The Vicariate includes the UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, the Republic of Yemen and the Sultanate of Oman. The bishop lives in Abu Dhabi, UAE. There are now 1,400,000 Catholics in the Vicariate, almost all overseas workers, 3.3 percent of a population of 42, 250, 000. Two Sisters from each community in Yemen were sent to Hodeidah to help. The other three members of the Hodeidah community were studying Arabic at the time in Sana’a.

Some Indian parishioners helped make the coffins. Sister Raphael MC arrived in Sana’a the following morning and the government welcomed Sr Nirmala MC with honors normally given to a diplomat. Bishop Gremoli also arrived.

Farewell Sisters

Next day the visitors headed for Hodeidah. Indian nurses had volunteered to help prepare the bodies for burial. They placed garlands of jasmine on the remains and a cross and rosary in the hands. On 30 July the procession left Hodeidah at 7:30 am. Because of a very heavy shower in this place known for its unspeakably hot and dry climate there was delay because of flooding. The cortege reached Aden nine hours later.

Bishop Gremoli and five priests concelebrated the funeral Mass. An Anglican priest did the first reading. In his homily Bishop Gremoli proclaimed the three Sisters ‘Martyrs of Love.’ At the end of the Holy Mass Sister Nirmala spoke about the dedication of the three and about the aim of the Missionaries of Charity. She then started the mission sending hymn of the Missionaries, God will take care of you. A sandstorm blew as the three coffins were lowered into the ground.

The 100 or so elderly and disabled people living in the Hodeidah Institute whom the Sisters had taken care of, and the 450 or so with mental and physical disabilities whom they served in the clinic there, were in deep sorrow. Some fasted and one asked Sr Nirmala if the Missionaries would leave Hodeidah. Sister Nirmala assured her that not only would the remaining Sisters not leave but that others would take the place of Sisters Michael, Zelia and Aletta.

The Unspeakable Grief

Sister Raphael reflected, ‘As a whole, these three martyrs were quenching Jesus’ thirst each moment by their fidelity to little things, and dying to their selves without counting the cost. As we ponder the last agony of our dear three Sisters who died on that street without a drop of water or a human touch or a consoling word, it seems unbearable for us who day by day for 25 years walked and worked without fear in Hodeidah.’

A few weeks after the murders, on 13 August, the Missionaries of Charity in utter poverty celebrated the Silver Jubilee of their presence in Hodeidah, enriched by the blood of Sisters Zelia, Aletta and Michael. When Victoria Espejon took her first vows as Sister Michael in November 1988 and even when she went to Yemen in 1995, she probably never imagined how her life would end or that a member of the security forces on duty at her funeral would say, ‘Being a Muslim, I found your prayers and your church beautiful. I found much more meaning in that all faiths were united, Muslims, Hindus, Anglicans and Catholics. I respect your faith.’

Meeting Mother Teresa

By Fr Michael Mohally SSC

The first time I was to have met Mother Teresa was in Hong Kong. I was asked to bring a package to her there from where she was to accompany Sisters into China to set up the first foundation of the Missionaries of Charity there. When I got to the convent I was told that the China foundation was on ‘hold’. Newspapers had got hold of the story and said that she was going there as the representative of the Pope. Rather than wait around Mother Teresa had gone to Hanoi to set up a new foundation there.

One evening back home in Manila I received a phone call from the Missionaries of Charity asking if I would preach at the community Mass the following morning. Mother Teresa had just arrived on a visit to the Philippines and was tired after her long journey. They were not sure if she’d be at the early Mass but since all the Sisters in the Manila area would be there, it would be a very special community celebration. I accepted the invitation very reluctantly. I was in awe of Mother Teresa and her reputation as a rather unique person. I discovered that the principal celebrant wouldn’t preach because of his awe for her.

I arrived the following morning and entered the oratory from the rear. The senior Sisters sat at the rear and novices and juniors at the front. A quick glance told me Mother Teresa wasn’t with the seniors so I gave a sigh of relief – she must be having a sleep after her long journey.

We began the Mass and I preached. In my homily I imitated the way a little baby kicks a blanket and holds on to one’s finger and won’t let go. A child finds his identity in what he ‘owns.’ I was aware that one ‘novice’ was really enjoying what I was saying. I was encouraged that the point I was making was being understood. I focused on the ‘novice’ and suddenly recognized the face. It was Mother Teresa. There she was sitting amongst her novices with this winning smile on her face. She seemed tiny to me.

I mentioned in my homily what had transpired between her and Jesus on a train journey to Darjeeling many years before when Mother Teresa was still a Loreto Sister teaching in an exclusive girls’ school. Jesus had told her that the thirst for love, acceptance and respect in the hearts of the poor was His thirst and could be their experience also asked for it. Mother Teresa nodded vigorously in agreement.

After Mass we spoke a little about our not meeting in Hong Kong. I recall her telling me how she had insisted with the Chinese authorities that the Sisters should wear their habit and she mentioned particularly the blue band around the sari, as she wanted it as a symbolic reminder that Our Lady was their protector.

Later that morning as the crowds gathered around for her blessing, she was distributing Miraculous Medals. I was standing some distance away from her and she beckoned to me to come over. With that smile and gentle laughter she said, ‘Father, I must tell you about these medals.’

She was once in Lourdes giving out some medals when a man approached her asking if he could help. She said that what she needed now was more medals. He promised there and then to keep her supplied with a few thousand medals each month. And then she said, ‘You know, Father, they arrive every month just as I am about to run out of them.’

I noticed a Middle Eastern couple in the crowd that morning. Their clothing spoke of wealth. I arranged that they be photographed with her. Later I discovered the man was very wealthy and had suffered a heart attack. He reflected on life and his accumulation of wealth, wondered with whom he could share this and had become a sponsor of the Missionaries of Charity. The feeling I had was that he and his wife had flown to the Philippines just to see and be near her.

Reflecting on the few occasions I met her, I would have to say it was her humanity that touched me. She was just a small, chatty old lady with a smile and a gentle sense of

humor. She seemed to wear the same worn sandals all the time. She was the personification of her own saying, ‘peace begins with a smile.’

A little child holds on to things to find its identity. ‘This is mine, that is mine,’ is what gives it its sense of identity. Our journey through life is meant to lead us to our letting go of things that we think give us identity – status, wealth, degrees or whatever – and discover that is God’s creative love that gives each of us our true identity.

Mother Teresa understood the story of the little baby. She understood the struggle of letting go and could laugh at it. What kind of sandals she wore did not really matter. She had grown to true Christian adulthood.

My Special Journey

By Father Ver Aro MSP

My appointment to the Western Province of Papua New Guinea was the start of my journey ad gentes – ‘to the nations.’ It was a kind of pilgrimage that led me to embrace the value of a very special vocation, to proclaim the Good News to a people and culture where Jesus’ words are unknown by most and when heard are often considered absurd.

I started to learn the local language, familiarize myself with the people I was serving, get acquainted with their culture and love the community. I also caught malaria. After only five months I was uprooted from the area because of an urgent need elsewhere. My superior transferred me to the Diocess of Vanimo in Sandaun Province.

The bishop placed me at Leitre Catholic Station. It was one of the old missions established by the SVD missionaries, developed by the Franciscans into a parish and then turned over to the Passionists. Now the MSP missionaries administer it. This mission opened my eyes to my ad gentescalling. It challenged me to become a true witness to my faith. I believe that my priesthood is not only for those who are already Christians but most especially for those who have closed the door on Christ. Through this, I have become an all-around priest: pastor, doctor, engineer, builder, mechanic, carpenter, hunter, cook and much more.

Many would say that missionaries are workaholics. However, this doesn’t apply to all. It’s not the works we do on mission that matter but the deepening of our relationship with God. This connectedness with God implants in my heart an attitude of self-giving and self-sacrifice. If this is absent I can’t survive the desert of sickness and the flood of the ‘missionary syndrome’ – loneliness – that can sometimes overwhelm a young priest on the frontiers.

In my mission experience I have the opportunity to share my faith without hesitation and also to respond to the call to transcendence. The remotest places give room for me to grow in my prayer life. It teaches me to hunger and crave for my God. In the company of the invisible God I find the tremendous joy and peace of my calling as a priest. He is my strength and source of energy to sow the seed of his love.

However, mission is also a call to be sincerely faithful and dedicated to the needs of the times. The call to obedience sometimes creates surprises. Recently, I was appointed Director of the Spirituality Formation Year of the seminarians of the Archdiocese of Port Moresby. I was tempted by the comfort of the stability in my bush parish to stay there, but there was a call to enter a tougher part of my journey where the Lord would ask me to let go of even more of myself. I’m convinced that my role in mission is not to find comfort or green pastures but to help the local Church grow in maturity and in self-reliance.

Our Hideaway

A

venue for the youth to express themselves and to share with our readers their

mind, their heart and their soul. We are inviting you – students and young

professionals – to drop by Our Hideaway and let us know how you are

doing.

Windows of Opportunity

By Lovelette B. Gonzaga

The sky was bright that Sunday afternoon as I was lying on our roof facing the beautiful velvet blue sky God was sharing with me. The leaves of the mahogany tree swayed to the rhythm of the gentle breeze that caressed my sleepy and stressful face. All this beauty unfolding before my eyes was enough to cheer me up and make me feel relaxed despite problems disturbing my brain.

Unwanted visitor

A young woman together with a man and a classmate from my high school days came to the house looking for me. Grandma yelled, ‘Candy, someone’s looking for you downstairs.’ At first I pretended that I didn’t hear and closed my eyes. But when Grandma continued calling and searching for me I ran down the stairs trying to hide from her. The three visitors had come to ask my help by inviting me to join their Choral Ministry, as they really needed a soprano.

Sharing my talents

I remembered the first time I joined a choral ministry singing at Sunday Mass. The schedule of practices didn’t fit my time to study, to relax and to serve. We finished practice between nine and ten at night. Home was far and that worried my family. No jeepneys stopped near our house at that time and I had to go home by myself. Still, I had always dreamed of sharing my God-given talents with others and at the same time glorifying the name of the Lord. But I left that first group because I wasn’t happy and contented. Later two other groups invited me to join but their situation was similar to the first and so I didn’t.

Where my heart belongs

Now I had another opportunity. I accepted the offer of the three visitors with the permission of my mother and grandmother. I attended their practices and services, offering every Sunday morning to God. Through my sharing and commitment I found another home, founded from above. With much feeling and a sense of comfort I sang with my new choir mates, or let’s say my other family, and at the same time I learned the beauty and wonder that most Catholics miss.

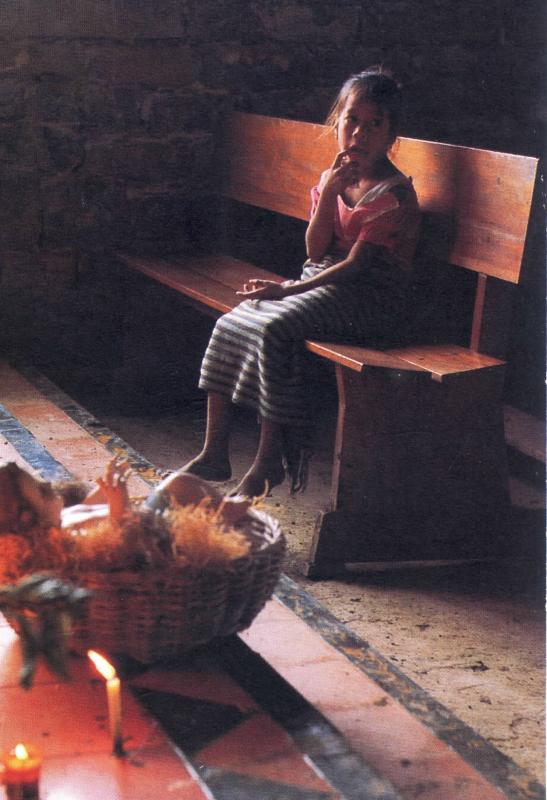

Stolen Childhood

By Father Shay Cullen SSC

Fr Shay Cullen of Ireland is a Columban Father working in the Philippines since 1969. He helps children imprisoned and abused by a corrupt judicial system. PREDA (www.preda.org) was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001.

Little has changed in the Philippine prison system since that day several years ago when I found a 6-year-old named Rosie behind prison bars clutching a drink can and crying her heart out for her mother. A dozen or so other street children were sprawled on the hard concrete floor, unconscious with exhaustion and hunger.

The toxic fumes they inhaled from a plastic bag filled with industrial glue, taken when local police rounded them up, had knocked out some. The cheap drug was their only remedy for the constant pangs from their empty stomachs. Rosie was too young for that. She had been taken from her mother who earned a living as a street vendor selling peanuts to tourists. She was expected to turn over her earnings to get her child released. It was extortion of the cruelest kind.

The Cries of the Oppressed

These were children of God robbed of their dignity and rights. It served as a stark reminder of the words of Jesus Christ when He told us that when we see the children of God, we see Him and whatever we do to them we do to Him. That night behind prison bars, I met an abused and abandoned God. There in those children, the God of the oppressed, the persecuted, and the innocent cried for freedom and love. It is the fate of thousands of children today, a fate Jesus willingly shared to remind us of our dignity, to tell us who we really are.

I was filled with anger and frustration as I worked to have those children released and brought to the children’s home I had set up in Olongapo City. Today, there are an estimated 20,000 children imprisoned in the Philippines. The prisons, such as the national penitentiary of Bilibid, south of Manila, are hellholes of abuse and neglect for children as young as 9. I know, for I have been jailed myself.

Robbed of dignity

In some city jails, the young girls are brought in from the streets to be sexually abused for a price by the guards and the adult male prisoners. In prison, sexual assault of young boys is all too common. Some are turned into child prostitutes while others are physically abused, leaving scars and psychological wounds in them all. This brutal experience can lead to a cycle of abuse and violence that fills the streets with young juveniles in continual conflict with the law.

Fighting back

Our organization, PREDA (Peoples’ Recovery, Empowerment, and Development Assistance Foundation), is doing all it can to save these children. Part of our work is organizing jail visits and investigating the case of imprisoned children with our jail rescue team.

We find many minors held in illegal detention whose rights have been violated. Some suffer from abuse, like the 8-to-12-year-olds brought to cemeteries by police and threatened with execution. Then they are tortured with cigarette burns until they confess to some crime for which the police want a conviction to get a reward and promotion.

Other young teenagers are jailed without evidence; they can be detained for weeks before seeing a prosecutor, lawyer or magistrate. Our efforts have helped release several children, but we find many more behind bars. It is not all doom and gloom for the imprisoned children of the Philippines and elsewhere if we work together to help them.

The First Time I Danced the Meke!

By Rowena ‘Weng’ Dato Cuanico

The following articles are by two Columban lay missionaries who have lived in each other’s country. Rowena is a Filipino lay missionary in Fiji. Paulo was a Fijian lay missionary in the Philippines. Read on.

I love to dance. So, when I arrived in Fiji in October 2000 as a Columban lay missionary, I became fascinated with the meke, a traditional Fijian dance that tells the stories of ancient legends.

To me, ethnic Fijians are natural singers and dancers, and I admire the way they move with grace and gentleness. After my arrival, I had soon promised myself, Au via meke! (I want to dance the meke!)

My chance to dance

The annual gathering of the Columban Companions in Mission, hosted by Holy Family parish of Labas in October 2001, proved to be my perfect opportunity.

I had told the principal choreographer and group leader, Aunt Clara – in Fiji you often call someone older than yourself ‘Aunt’ or ‘Uncle,’ like ‘Ate’ and ‘Kuya’ in the Philippines – that I wished to dance themeke. I had some reservations because I thought that I couldn’t be as graceful as the other dancers. Perhaps I would spoil the performance! But the dancers were so encouraging to me, it kept me inspired.

Practice started two weeks before the gathering, but since it was the busiest week of the year in our apostolate to the Indian-Fijians, there was simply no time to join their nightly practices.

Getting to know the

Meke

Finally, three days before the Columban Companions’ gathering, I was able to join the practice. Friendly faces greeted our arrival, and I was welcomed warmly and sincerely by the women who were dancing as well as by the choir practicing a song composed especially for the occasion. Since I am primarily involved in the Indian apostolate, it was my first time to be alone with a purely indigenous Fijian group. But I did not feel like a stranger because I knew them and they knew me.

I had planned to sit and watch them dance, but they told me to stand and join them. They said the best way to learn the meke was to do it.

The singing and symbolism were pure Fijian. Since I had been trained in Indo-Fijian culture, I felt helpless. However, the dancers, particularly Aunt Una, La Maria and Asilika, were always willing to help me. Seleka was creative in translating Fijian words and dance steps into English for me. She would tell me, ‘Fly, Weng…fish, Weng…pull, Weng, carry it, Weng.’ These words seemed inappropriate in the dance sequence, but it worked. I enjoyed every minute of the practice because everyone was encouraging and helpful.

As the participants arrived from Suva, Ba, Lautoka and other places on the first day of the gathering, I was in the Holy Family Primary School canteen practicing the meke with Aunt Maria.

Preparing for the performance

On Saturday, I was becoming more afraid. I could not recall any of the steps! We were going to dance before the soli (offering). So right after lunch, we gathered in the primary school to get ready. I felt like a bride being dressed for her wedding.

I changed into a red top and a white sulu (a wraparound skirt) that Asilika lent me. Then Aunt Una wrapped the masi (bark cloth), with its carefully made pleats, around my waist. She then put the white salu-salu (a garland made of paper) she had made for me around my neck and hands.

My excitement, tempered with nervousness, was showing. I hoped we could start soon and get this over with. We were ready for my finishing touches: a garland of green leaves wrapped around my waist and flowers adorning my head.

As Aunt Clara put the teki-teki (flowers) on my head, I felt I was part of the ritual. Since Aunt Clara had to touch my head, which is taboo in Fijian culture, she had to first excuse herself by saying ‘tilou.’ I gave her permission to touch my head, and even then she only touched my hair. Oil was applied to my hair so the flowers made from kula (thread) would stick. Aunt Clara beautifully and carefully arranged the teki-teki.

Greatest performance of my life

The people had already gathered and were waiting for us and the choir to start. When my friends saw me, I could see their surprise and excitement. As we got into position, I could hear Aunt Seleka praying, entrusting our dance to the Almighty. Aunt Clara’s last words to me before we made our entrance were, ‘Relax and enjoy it, Weng.’

I could hear the audience laugh whenever I couldn’t follow the steps. But the mistakes did not matter, the applause and the laughter did, and that’s what kept me going. Afterward, the Columban Fathers, Companions and my fellow Filipino lay missionaries offered their thanks, support and admiration (perhaps!).

During the third dance sequence, I could feel my adrenaline flow. I was following the steps better than before. I became less self-conscious and concerned if I had taken the right step or not. I was dancing with my heart and enjoying it.

Dancing my way to their culture

As I look back on this remarkable experience, I realized that not only did I dance the meke, but journeyed into a unique and amazing culture.

The meke is a ritual, with the lyrics of the songs, that showed our appreciation to those who came to join us in celebration. We were thanking the Columbans for the gifts of mission, faith and love. We were remembering people who had served the Holy Family parish and the people of Labasa. We were praising God for bringing us together as a family united in faith.

I thank God for allowing me to experience the meke, for it was a modest step towards learning the culture of indigenous Fijians. For by discovering the uniqueness of their culture, I can understand them better and together we can celebrate this wonderful gift. I feel that this is a challenge to me as a Columban lay missionary.

I will always remember with joy and gratitude in my heart the first time I danced the meke because it was an amazing experience, because of the wonderful people who cared for me, and because of the unique culture I experienced. I thank God for all of these gifts.

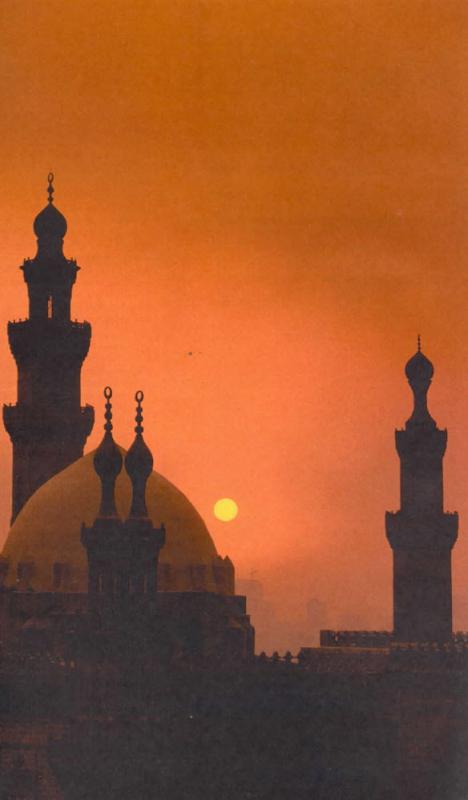

What Chance Does A Missionary Have In A Muslim Country?

An interview with Archbishop José Antonio Peteiro Freire OFM

Of Tangier, Morocco. By ZENIT (www.Zenit.org)

The lack of religious liberty in some Muslim countries raises the question of whether a missionary can function at all in a nation dominated by Islam. In this interview on 3 February 2003 Archbishop Freire says the key to the answer is in witness.

Q: Let’s begin with the fundamental question: Is it possible to be a missionary in a Muslim country?

Archbishop Peteiro: St Francis sent five Italian Franciscans to Morocco. The Franciscans preached the Gospel openly and declared that Islam was a false religion and that Mohammed was a false prophet They went to the mosques in an insulting way, and this is why they were killed the following year, 1220.

In 1219 St Francis went to meet the Sultan in Damieta, near Cairo, and asked that Christians be allowed to visit the holy places. The fact that he went out to meet the Sultan was, undoubtedly, a prophetic action.

At the height of the Crusades, when the Muslim and Christian armies were confronting each other, Francis had difficulties in getting the permission of the papal delegates, named Pelagius, to meet with the Sultan. In fact, however, he treated him well and gave him a golden trumpet.

Our presence among the Muslims has two purposes. The first is to help Christians to be true disciples of Jesus. In the second place, St Francis wrote in 1221 a 23-chapter rule. Chapter 16 talks about ‘those who go among the Saracens and other infidels.’ The text says: ‘So, therefore, any Brother who wishes to go among the Saracens and other infidels, must go with the permission of his minister and slave . . . Moreover, the Brothers who go and live spiritually among themselves in two ways. One, not promoting disputes and controversies, but submitting to every creature for love of God . . . and confessing that they are Christians. Another is that when they see it is pleasing to God, they should proclaim the word of God so that they, the infidels, will believe in the Omnipotent God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit . . .’

The first way is always valid in any circumstance. With regard to the second, Francis cautions, ‘When they see that it is pleasing to God.’ It does not always please God that we proclaim the Gospel by word. It might cause dispute and quarrels.

Q: In Morocco, there is freedom of worship for Jews and Christians, but all proselytism and conversion to Christianity is prohibited. What can a missionary do where evangelization is explicitly impeded?

Archbishop Peteiro: The Christian must be a universal brother, open to all without distinctions, preserving his own identity, but establishing bridges of respect, friendship, solidarity with the whole world. This is another way of evangelizing, perhaps more costly and more exacting than that by word. We are called to live evangelical values like love, justice, forgiveness, solidarity with everyone, especially with the poorest.

Q: Has the situation of Christians in Morocco changed since Sept. 11, 2001?

Archbishop Peteiro: A prayer meeting was organized for the victims in the cathedral of Rabat. The Moroccans government is with the United States. However, the people have protested against the Americans. The Moroccans tend to identify the West with Christianity, hence their rejection of both concepts.

Q: Is there room for interreligious dialogue in Morocco? What relation can be established with Muslim religious leaders?

Archbishop Peteiro: Muslim religious leaders are convinced that Islam is the religion of God. They tend to speak only Arabic and avoid interreligious dialogue because, according to them, they have nothing to learn from other religions. However, with some cultural institutions, some NGOs, in the sports, artistic, cultural and educational realms there tends to be interesting cooperation that promote the country.

Q: How does a country with 99% Muslims benefit from the Christian presence?

Archbishop Peteiro: The fact that the Christian presence is permitted in Morocco is enriching for the country. First of all, it means that there is a certain variety in Moroccan society, which, in my opinion, benefits all and is a positive sign.

Moreover, the Church offers multiple services to the poorest sectors of the population. In addition, it exposes society to other languages, cultures and civilizations in the world of literature, the arts and sciences, which represents a richness for the country.

It is too bad that religious liberty is not accepted in any Muslim country. What is more, Tunisian historian Mohammed Talbi said recently that, given that they live in dictatorial regimes, the reformation of Islam will come from minority Muslim communities that live in the West, which is where there is freedom.

Q: What characteristics would you highlight of the work of the Friars Minor in Muslim countries?

Archbishop Peteiro: Someone has said that it is a charism within the Franciscan charism. Of course, w have been living with Muslims for about eight centuries. Only for two periods – of four years each – were we expelled from Morocco.

In the course of these eight centuries, we find different types of friars: the martyrs, the friars at the service of captives, peace mediators, those dedicated to pastoral ministry, those who worked in the country’s development. Among others, mention should be made of Father Joseph Lerchundi.

The service to captives in Marrakech, Fez and Mequinez was impressive, where they lived with the prisoners, shared the same dungeons with them, that is, an underground, vaulted, lugubrious and damp place. Inside these dungeons, the religious had their own living quarters, a chapel and infirmary. They shared all the problems of the captives and tried to help them with all the means within their reach.

Since 1217, the Holy Land mission is considered the ‘pearl of the missions.’ The Holy See has entrusted to the order the charge of the custody of the holy places, the promotion of divine worship in them, the fostering of pilgrims’ piety, the carrying out of evangelization, and the establishment and promotion in the apostolate of works of a social character.

‘I Will Walk With Faith’

By Alma Pangsiw

Alma is from the Mountain Province. She was a strong and healthy person, determined to reach her dreams for her family. But a sudden illness got in her way. Here she shares with us how she continued to walk with faith.

Alma is from the Mountain Province. She was a strong and healthy person, determined to reach her dreams for her family. But a sudden illness got in her way. Here she shares with us how she continued to walk with faith.

I am the eldest of five and was determined to finish college and find a stable job to help my brothers and sisters through school. Then fate walked in and closed that door.

August 18, 2000. I woke up and felt a sudden pang in my hips and waist. My hands were trembling and sweating. I tried to stand but couldn’t keep my legs from shaking. Yet I managed to get dressed and went to the high school where I was having my teaching practice. I couldn’t keep standing during the flag ceremony because of the throbbing pain. I could also feel both legs getting weaker. After one class I thought the pain would subside but it got worse. I couldn’t bear it anymore. I felt I’d collapse and asked permission to go home.

By the afternoon the pain hadn’t ceased! The pain reliever I took proved useless. So I just went to bed moaning, and stretching my back and legs. Around 9 o’clock I decided to go to the hospital, walking distance from our boarding house. Slowly and deliberately, I pushed myself to a standing position but was startled to discover that I couldn’t move my right foot. Even when I stood I needed someone to assist me. My two board mates gladly supported me down to the hospital.

The progress of the paralysis was so fast that by now my right leg was totally numb.

The second night was torment, as if a bolt of electric pain was running through the vein and muscle of my legs. I really cried in pain. But thankfully, I was able to sleep as dawn was breaking. When I woke up, I knew something was really wrong! I couldn’t feel the floor under my foot nor that I was sitting. I shuddered at the realization, I’M PARALYZED!! This can’t be. My head seemed to burst with shock! Both my feet were totally immobile, except for the big toe of my left foot. I tried to raise them but couldn’t. Slowly, as the reality sank in, tears rolled down my cheeks. It was as if the world had stopped and stood still as I felt the anguish of my soul. I cried and cried, asking myself questions I knew only God could answer.

Then Mom arrived. As she lovingly gazed at me, with eyes full of pain, she blinked her tears away. I knew she wanted to give me strength, comfort, support and love, to face what was before me. That moment I came to fully appreciate her great love for her children. She brought warmth and comfort to my somber mood. I was tearfully grateful for the undying love and support she’d always given me.

On the third day, half of my body was totally numb from the waist down. I was only able to move my head and hands.

The following day, I was transferred to the intensive care unit, (ICU), while Mom and the physicians made decisions. Alone in the ICU, fear slowly engulfed me. The stark reality frightened me. I hated to admit it: I was afraid to die! Flashbacks of my past suddenly came alive. Had the good things I’ve done outweighed the bad? I rated myself as not being expected in heaven, that my soul would definitely be damned. Thinking of hell made me shiver. Then something popped into my mind. Maybe there’s something I can do before I run out of time. Even if I can’t alter my fate, at least I can do good before going into the void of nothingness. I remembered the quarrels at our boarding house. So I made up my mind that I’d ask forgiveness of all I’d offended and hurt.

That afternoon, since they couldn’t stop the paralysis, the doctors decided to transfer me to Baguio General Hospital. My friends, board mates, and some relatives came rushing to see me and wish me good luck. I could sense their love and concern. Each was looking at me with misty eyes. Amidst the chaos in my mind, I thanked God that I still had a clear mind and was able to talk. Calming myself, with a half-croaking voice, I asked for forgiveness. I was happy I’d done this and felt relaxed and composed.

On our way to Baguio, it seemed unreal, like a bad dream. Yet deep down inside me I couldn’t deny the truth. As I gazed out of the ambulance, I had a wonderful feeling, as if a soft whisper was caressing my ear telling me that all would be fine. I just had to trust God. That very moment I noticed I was already truly praying, asking His forgiveness, thanking Him for all his blessings and fervently asking for a second life. It was only then that I truly communed with the Father. That was the beginning of a more contemplative life.

In the hospital I saw patients come and go. I also saw faces of death and how pain distorted the faith of some while it strengthened that of others. Slowly my eyes were being opened and my mind illuminated. God was already working on me, by letting me see the truth and the reality.

After three months, my situation seemed no better. Although the ascending paralysis stopped, I was totally paraplegic. The doctors thought my case would be reversible but as 60 days passed I still hadn’t progressed. That’s when they decided to let me have magnetic resonance imaging, (MRI), in St Luke’s. The MRI found that a small vein was swollen, blocking other veins and so blocking the message from the brain to my legs. That was why I couldn’t move them.

The doctors then suggested an operation that would cost between P80, 000 and P90, 000. Where would we get such money? The chances of survival were 50-50. If the operation was successful they weren’t sure I’d recuperate well. I might be normal or I might be comatose. We decided against an operation. I’d rather be alive and like this forever than gamble with my life. It seemed I was drowning, my mind swirling in limbo. All my hopes and dreams were dashed forever. I thought at that instant that dying would be sweeter and wonderful. There was no use in living. I’d be just a burden to my family. Yet my life had a purpose, it seemed, for I was still here in this world.

After I left hospital we never stopped seeking help from well-known faith healers and mga manghihilot. We tried almost everything. Bit by bit there was an improvement. But I also realized that we could be blinded by our desire to be healed. Some, in desperation and depression, had chosen suicide.

Today with the aid of crutches I can already walk to and fro across the room. Both legs are still numb but I can deliberately use and move them now. Though not totally healed, I’m still thankful to God. Everyday is a new opportunity to learn. I’ve discovered who my true friends are, friends in good times and in bad. I’ve understood and felt what it’s like to sit all day in a wheelchair, what’s it like to be unable so see the beautiful sunrise and sunset.

Yes, God has a plan for me, to bless and not to harm. I just have to trust Him. This way He can bring out the best in me. Sometimes it’s through trial and difficulties that our talents are refined. Stuck in my wheelchair, I’ve grabbed the opportunity to learn how to play music.

The most important thing is to have faith, faith to trust God and His words no matter the circumstances are, whether or not He does miracles, faith to wait for His promises to come to pass, regardless of what we experiencing at present. May I walk with faith!

‘Maestra di Campagna’

By Sister Sonia Sangel FdCC

‘If everyone lit just one little candle, what a bright world this would be!’

This is what my heart was singing as I began my mission in East Timor a few months after the war in 1999, my second mission ad gentes – ‘to the nations’ – after six adventurous years in Papua New Guinea. I wished to be one of many who might light just one little candle, particularly in the world of women. Women constitute 49.5 % of the population of East Timor. By their sheer number alone they can be looked upon as key economic and social agents in this newly born, struggling nation.

Stereotyped

Many East Timorese don’t yet seem to fully appreciate the right of children, particularly of girls, to education as a vital factor towards self-actualization, giving them access to possible key decision-making positions in both governmental and non-governmental institutions. A multitude of traditional practices and the absence of laws in this area make the identification of women’s needs and capacities, as well as their promotion, difficult. This is the darkness of the world of women in which a tiny candle needs to be lit.

Empowering women

About 80 Canossian Sisters engaged in formal and non-formal education, evangelization, pastoral and health work, assist men and women in all age groups to develop themselves to take an active part in the building up of the Church and nation. However, in all the communities, we minister to women in a special way through seven students’ boarding homes and on-the-job training for women working side by side with the Sisters, and the handicraft skills training conducted for many groups of girls and women. In Baucau, together with the young Timorese Sisters of my community, I started one of the typical pet projects of St Magdalene, our Foundress, which is still very relevant and fruitful, the ‘Maestra di Campagna’ or ‘Rural-Teachers’ Training.’

Women aged between 19 and 40 from different villages and districts of this small country, on the recommendation of the parish priest, community leaders or Sisters, attend the six-month, stay-in training. St Magdalena admonished the Sisters to ‘commit themselves to the formation of women’ so that ‘by helping the country women, they become guides and animators of their local ecclesial communities.’ So we, the Sisters, exert joint efforts, and with enthusiasm and zeal, dedicate ourselves to this training. The course entails: Leadership Training, Catechism, Music, Spoken English and Skills in: Computer Literacy, Sewing and Embroidery, Cooking and Baking, and Organic Gardening. The Timorese Sisters and lay staff take charge of the Catechesis, Sewing and Embroidery, Cooking and Baking, while I teach English, Computer Literacy, and Organic Farming, which is my magnificent obsession. However, my main task is to keep the program running by securing funds. Thank God the ‘well never runs dry.’ It is always replenished by good friends and benefactors.

At the end of the six-month training, we aim to produce empowered, responsible and skilled women capable of loving themselves and others, committed to their mission in the local Church. These women are qualified for employment in the community, or for self-employment while upholding the importance of basic education and the dignity of labor.

What happens after the training? What becomes of these women?

Here are some of their testimonies.

I am Elda. I belong to the first group of ‘Maestra di Campagna’. At the beginning, I was hesitant to accept the offer of our Parish Priest, Fr Locatelli SDB, to attend the course. The trauma of war is still in my senses and to live away from home gave me some insecurity. Yet, I trusted that the training would give me a brighter future. I have a dream to work for and serve the people in our little village. So, I attended the training. It was a period of adjustment, of insertion in a group and of discovery of myself and the community. I learned to trust myself and to be available for the service of the community. Now I have a group of women to whom I teach catechism and sewing. It gives me a sense of dignity to work for my living while empowering other women too.

I’m Christine. I learned to cook and bake. Right after the training, my colleague, Nicolina, and I got work as assistant chefs at the airport in Baucau. We cook the meals for pilots, engineers, medical teams and aircraft crews coming from all over the Pacific and Asia. It is challenging work where I learn to become more creative in cooking every day. I feel satisfied to see everyone happy at mealtimes. On weekends Nicolina and I give our time to our local community, especially for the formation of youth.

I’m Georgina, the mother of two children. The skill I learned best in the training is sewing. My two little children keep me at home. Thanks to the Sisters who gave me a sewing machine, I sew some dresses, aprons and trousers while my children are asleep. I’m happy to have an income which I can use to buy milk for them.

I’m Jacquelina. I’ve always wanted to become a professional working in an office. But I was not quite sure whether this would come true since my family had no means to finance a tertiary education for me. Providentially, my aunt who helped the Sisters to repair their sewing machines, encouraged me to take the ‘Maestra di Campagna’ course. Amazing! When I began to use the computer, ‘My dream seems to have come true.’ I felt my dignity and self-esteem. My teacher saw my keenness in Computer Literacy. I also made good progress in English. Now I am employed as a secretary in Canossa Foundation, Dili. I do computer work, keep correspondence in English and Bahasa Indonesia and do the bookkeeping. I also attend NGO forum meetings as representative of the Canossa Foundation. Thanks to the good Lord and to the Sisters who have helped me become what I am now.

Indeed, education, whether formal or non-formal, is a way of preparing persons to take roles in society. . . a kind of transformation happens within a person where she feels empowered with self-worth and confidence, and does things not only for herself but also for the common good. This is the little candle which we try to light in our own way…in the way inspired by St Magdalene, our Mother and Foundress.

Lastly, I wish to thank all our friends and benefactors and our Director who generously and enthusiastically support the training in ‘Maestra di Campagna.’ They too light little candles to brighten the world.

‘You Need New Shoes. . . Will I buy you a Black Pair?’

By Father Seán Connaughton SSC

A student for the priesthood in Ireland used to be recognizeable by his black suit, hat, tie – with white shirt – and shoes. While walking in a field with my father in the summer of 1955, he said to me, ‘You need new shoes. . . will I buy you a black pair?’ I knew that whatever opposition I thought he and my mother had to my desire to be a Columban priest was over. Maybe they’d never opposed the idea but there was no one on either side of the family who had ever become a priest and I didn’t see myself as particularly religious.

A student for the priesthood in Ireland used to be recognizeable by his black suit, hat, tie – with white shirt – and shoes. While walking in a field with my father in the summer of 1955, he said to me, ‘You need new shoes. . . will I buy you a black pair?’ I knew that whatever opposition I thought he and my mother had to my desire to be a Columban priest was over. Maybe they’d never opposed the idea but there was no one on either side of the family who had ever become a priest and I didn’t see myself as particularly religious.

For a long time I had dreamed of being either a teacher or an accountant. A secondary dream was to be a horticulturalist, perhaps because of all the planting we did when I was a child during ‘The Emergency,’ the name given in Ireland to World War II in which we were neutral.

Seeds of my vocation

Maybe the Lord planted the first seeds of my vocation during my high school years when religion was a very serious subject. Most of us were boarders in St Finian’s, a school for boys owned by the Diocese of Meath. In second year, to my amazement, I was given a daily missal on the day of the bishop’s visit. I think it was from this I got a real feel for St Patrick, who brought the faith to Ireland, and for the many Irish saints such as St Brendan and St Columban who subsequently took to heart the ‘go forth’ passages of the Gospel. For some reason these same passages stuck in my heart. The parable of the talents also struck like irremovable acid, especially when explained by the priest who taught us Greek.

Another item had never left my mind. This was the memory of how I almost drowned in a river while still in elementary school. Was it that life is ‘dispensable’?

What triggered me?

When I finished in St Finian’s I began to study accounting. In my boarding house I began to receiveFar East, the Irish equivalent of Misyon. ‘Who on earth is sending this?’ I asked myself. I never found out but later discovered that each student in St Columban’s was asked to send Far East to the address of a contemporary. The stories about China fascinated me. What we now call ‘social, political and cultural’ phenomena in community growth, and what seemed non-formal disorder, seemed well answered in the churches. I recall a sentence, ‘This may be what you are looking for; and if you don’t do it, who will?’ It seems a bit out of form for 2003. But it had meaning for me then.

No more China

I went for an interview with the Columbans early in 1955 and was accepted. My father bought me the new shoes I needed, along with other requirements, and I entered St Columban’s the first Tuesday of September. I had two negative experiences that day. One was the despicable, second-hand blacksotana I was given to wear during most of my waking hours. (By the end of the month I had my own new one.) The second was a lecture telling us very clearly, ‘No more China.’ The last Columban to work there had been expelled by the Bejing government the previous year.

Seminary life was a struggle. About one third of our class made alternative decisions during our seven years there. The human formation in those times of pruning, fostering, watering and cutting down to size, was often antiquated. But you were still free inside your own head.

Interest for China

China still intrigues me. A few years ago the China People’s Daily published a decree about upholding ‘materialism’ against the ‘opposing spiritualism.’ The authorities have been cracking down on theFalun Gong, a group in search of meaning in their lives beyond what the Chinese Communist Party can offer. They claim to have 100 million followers, three times the membership of the party. They’re trying to create a different ‘style of life’ and we learned in the seminary that that was one of the definitions of the spiritual.

Nevertheless, since the People’s Republic opened up some years ago some Columbans, including Filipinos, have been able to go in to teach English. Many teachers have gone in with the AITECE program (www.aitece.com) that the Columbans facilitate. As the poet John Milton said in On his Blindness, ‘They also serve who only stand and wait.’ This is ‘a style of life’ chosen in order to prepare the way for the Lord.

Nearly all of my life as a priest has been in the Philippines. Of course I don’t regret the grace of being able to work for many years trying to build Basic Christian Communities. It seems it’s always been ‘ten steps forward and eleven steps back’. . . by no means successful. However, as Milton wrote in Paradise Lost, ‘What though the field be lost? All is not lost.’