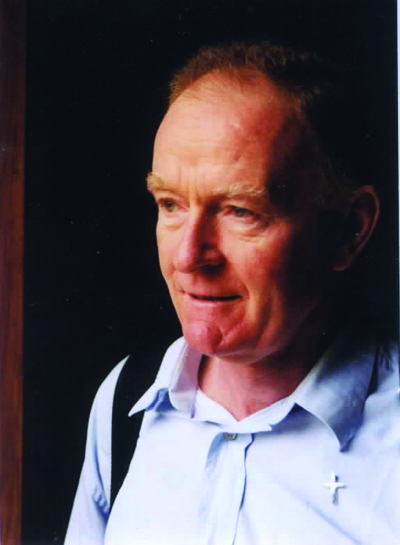

Pareng Rufus

By Gaudencio B. Cardinal Rosales

The author, after ten years as Archbishop of Lipa, his native diocese, was appointed Archbishop of Manila by Pope John Paul II on 15 September 2003 and created cardinal by Pope Benedict XVI on 24 March this year.

A young Bishop Rosales, seated, second from left, with Fr Bernard Jagueneau of the Little Brothers of Jesus. Far left, another close friend of Father Rufus

I first met Father Rufus Halley in the mid-1970s when I was appointed auxiliary bishop in Manila with responsibility for Rizal Province, the area that became the Diocese of Antipolo in 1983. The Columbans had been working in parishes there since before the War. Father Rufus was in Jalajala at the time. Father Feliciano Manalili, a diocesan priest, introduced me to him. Father Manalili is now a Trappist monk in Mepkin Abbey, South Carolina, USA, www.mepkinabbey.org , where he is prior.

New friend

At first I knew Father Rufus in a formal way, as one of the parish priests under my jurisdiction. But I gradually began to know this man with an open personality and a wonderful sense of humor as a person. On one occasion he invited me to a barrio in his parish that was 45 minutes by boat from thecentro. He had forewarned me that this would be a different kind of pastoral visit. We set off in the afternoon. The house where we stayed was on a duck farm and some of the birds were waddling around the house. There was no electricity. After dinner we walked around the village. I saw the people at their usual occupations that included drinking and gambling games such as bingo. Father Rufus introduced me as ‘my friend from Manila,’ which wasn’t untrue, as we were in the Archdiocese of Manila.

Back at the house we chatted for a long time and prayed together. We decided we’d celebrate Mass the next day back at the centro. We slept on the floor. As we were leaving next morning people came to see us off and it was only then that their parish priest told them that I was the area bishop. Though there was some embarrassment, especially among those who were members of Church organizations, there was a lot of laughter at the realization that the bishop had met them as they really were.

Tagalog speaking Irishman

'My friend Rufus wanted not only to know the faith and culture of Muslims but to "befriend the culture of our brother Muslims". More than that, he wanted to understand the culture of the Maranaos.'

By this time Father Rufus and I were close friends and I called him ‘Pareng Rufus’ and he called me ‘Pareng Dency.’ I felt free to drop in on him any time and to go through the back door of hisconvento. Sometimes I wouldn’t find him in the office or upstairs and would then realize that, despite his red hair and blue eyes, I had passed him in the kitchen, where he was chatting with the staff. (His baptismal name was Michael but his parents always called him ‘Rufus’ because of his red hair). What threw me was that I’d hear only pure Tagalog while walking through the kitchen. My Irish friend spoke the language perfectly.

Another trademark of Father Rufus was his bakya. I learned from the late Father Patrick Ronan, then parish priest in Morong, that Father Rufus came from a privileged background. That was a revelation to me, as I had always been struck by the simplicity I saw in his life. Father Ronan, another Irish missionary with a great sense of humor and known to his fellow Columbans as ‘Pops’, had spent time in jail in China after the Communist takeover in 1949.

Around 1980 Father Rufus felt called by God to leave the security of living in an overwhelmingly Catholic community to work in the new Prelature of Marawi, which includes all of Lanao del Sur and part of Lanao del Norte, where 95 percent of the people are Muslims. He was very aware of the long history of tension and occasional outright conflict between Christians and Muslims. He also became fluent in two other languages, Maranao, spoken by the Muslims in the area, and Cebuano, spoken by the Christians.

His kind of dialogueo

I too moved to Mindanao, becoming Coadjutor Bishop of Malaybalay in 1982 and succeeding Bishop Francisco Claver SJ in 1984. On one occasion, after spending about a week on retreat in the Benedictine Monastery of the Transfiguration in Malaybalay, Pareng Rufus came to spend a night at my place. He spoke of a ‘brother Muslim’ whom he loved very much and told me that he had been hired to work in a store in the market in Malabang, Lanao del Sur. ‘Why?’ I asked him. ‘This is my kind of dialogue,’ he told me. He was pushing Christian-Muslim dialogue to the limit. When the late Bishop Bienvenido Tudtud, first bishop of the then Prelature of Iligan, which covered the two Lanao provinces, told Pope Paul VI of the conflict there and of his vision of a ‘dialogue of life’ between the two communities, the Pope encouraged him to the extent of dividing the prelature and transferring him to Marawi. Bishop Tudtud died tragically in a plane crash in 1987.

Male dominated Maranaos

My friend Rufus wanted not only to know the faith and culture of Muslims but to ‘befriend the culture of our brother Muslims.’ More than that, he wanted to understand the culture of the Maranaos. This involved trying to understand aspects of that culture that went against his own warm nature and that didn’t seem to be in harmony with the Gospel. For example, he noticed that among Maranao men it wasn’t seen as proper to show any public signs of softness, even if a child of theirs was hurt. He noticed how stiff Maranao men are in their dances which many Filipinos are familiar with. Men sometimes carry a kris as a sign of power. He was well aware that many men, Christian and Muslim, carry a gun for the same reason, and not only in Lanao. He asked himself if there were any areas of tenderness in the macho culture of the Maranaos and stressed the importance of trying to find ways in which the Gospel could enter into dialogue with that culture.

Pareng Rufus was really educating me that night.

Who inspired himo

I knew of the intensity with which Father Rufus lived his own Christian faith, how he began each day with an hour of adoration before the Blessed Sacrament, the centrality of the Mass in his life. A big influence on him was the life of Charles de Foucauld, 1858-1916, beatified last November. This Frenchman was also from a privileged background. Unlike Pareng Rufus, he lost his Catholic faith and became a notorious playboy before re-discovering it, partly through the example of Muslims living in North Africa. He spent many years as a priest living among the poorest Muslims in a remote corner of the Sahara, pioneering Christian-Muslim dialogue by discovering himself as the Little Brother of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament and as the Little Brother of the Muslims who came knocking at his hermitage door.

Death of a peacemaker

On 1 December 1916 Charles de Foucauld died at the hands of a young gunman outside his hermitage and on 28 September 2001 Pareng Rufus died at the hands of gunmen who ambushed him as he was riding on his motorcycle from a meeting of Muslim and Christian leaders in Balabagan to his parish in Malabang. The local people, both Christian and Muslim, mourned for him deeply. The grief of the Muslims was all the greater because the men who murdered my Pareng Rufus happened to be Muslims. This great missionary priest brought both communities together in their shared grief for a man of God, a true follower of Jesus Christ.