‘We’re Kiwis’

By Father Bobby Gilmore

FOR MY FATHER

Our trivial fights

over spading

The vegetable patch,

painting the garden fence

ochre instead of blue,

And my resistance

to Armenian food

In preference

for everything American,

Seemed, in my struggle

for identity,

to be the literal issue . . .

This poem, by the son of Armenian immigrants, directs a shaft of light into the hidden mesh of emotion and tension that is unconsidered in the lives of the uprooted as they try to re-root. Both Armenian father and American son are trying to express in an oblique way that which is near and dear to them. Both feel they are unheard.

When I began working in Britain, migrants from Ireland frequentlycommented that their children were of a different nationality, weren’t interested in things Irish and weren’t Catholics. They generally asked, ‘Where did we go wrong?’

Who am I?

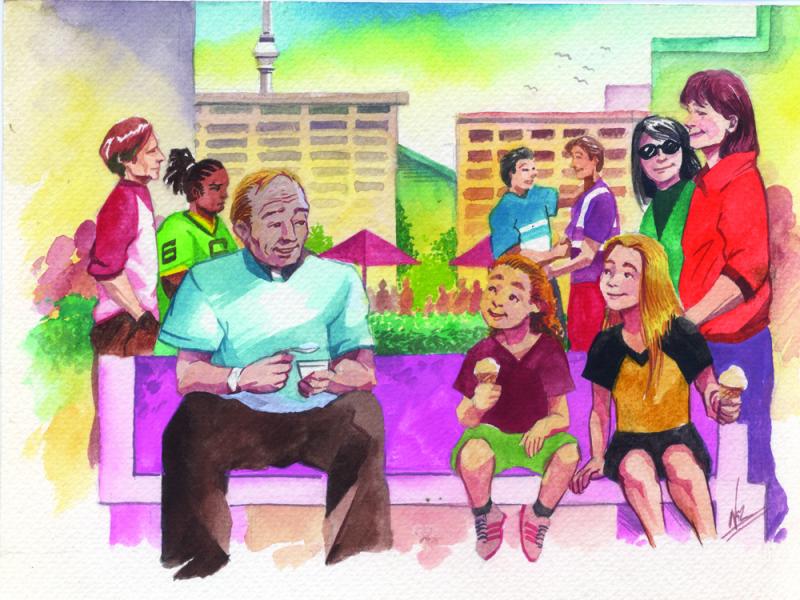

I wouldn’t have been able to appreciate their feeling of loss were it not for an incident that happened some years previously in New Zealand. Sitting outside an ice cream café in Wellington with my two nieces, aged nine and ten, and seeing the wide variety of people passing up and down the street, I remarked on the presence of so many different nationalities in New Zealand. One of my nieces replied, ‘There are three in our house’. Asking who they were, I got the reply, ‘Mum is Australian, Dad is Irish and we’re Kiwis’. This was an aspect in the life of immigrants that I was totally unaware of. However, during the New Zealand/Australia cricket match on television the following week it was obvious who was who.

The experience of immigrant parents in coping with the ‘loss’ of the new generation, their sons and daughters, expressing their affiliation to different signs, symbols, values and a worldview is difficult to address and come to terms with. Of course many immigrants do not have time to reflect on these issues other than in passing regret and speculation. Seldom if ever have departing states or the arrival states of immigrants done anything to explain the momentous loss and change that is taking place in their lives that will continue into the future. States seem to see immigrants as objects of security rather than people who are experiencing a break in primary relationships.

Modern exodus

In the past, as is also the case at present, with some exceptions, immigration progresses from a rural village to an ‘edge’ city from which people migrate into a wider foreign world. They are in a threshold process with few, if any, external supports. Indeed, they are even perceived as suspect. The unfamiliar is threatening. In this situation, immigrants draw on their internal resources, central to which is religion. Generally, their religious belief, values and worldview have been determined for them by the overarching view of reality by village influences, customs and traditions.

A place for faith

Religion, which before may have been passive or functional, carried out under social pressure in their lives, now becomes central and its signs and symbols in high streets which were taken for granted now become beacons in the storm of their living on the edge of uncertainty. Religion and an awakening of national identity take central stage in immigrant lives and these are reinforced in the new destination by the networks of the ghetto, church, mosque and temple. Here there begins a longing to replace the overarching beliefs, values and traditions of the village they left behind.

A world of their own

This longing is reinforced if the religious leader is caught up in the same time wrap and tries to re-create the village with decor and doctrine irrelevant in enabling the new immigrants to access the new networks, the cultural norms, traditions and customs of their new world. As their village and national viewpoints are challenged by the discomfort of the indifferent and in some instances hostile, there is a tendency to view the new surroundings and people in negative ways. These negatives may have been imparted, nurtured and determined by biased historical, nationalistic and moralistic values that will lead to a rejection of the new rather than an understanding of it and relating to it with an appropriate faith expression that enhances one’s own and the new society’s well being.

Frequently, it is in such a negative scenario that immigrants settle and are determined by. Their longing for the past re-enforced in the present keeps them prisoners of the past rather than pathfinders. Fiction can easily become folklore at the expense of history.

However, even if economically comfortable, their greatest tension is yet to come. Naturally, immigrants settle, marry, have a family and the real tether of a mortgage.

What about the children?

Who will the children be? If they are born into an atmosphere of embellished decor, doctrine and culture from the village their parents left, the expectation will be to hope their children will be ‘like their brother’s and sister’s children back home’. However, the only comparison they can have of ‘home’ in the new situation will be the texture of their local church, temple or mosque and the tourist brochure picture that has been planted in their minds of ‘home’.

In modern times this is a major issue for many immigrant groups. The parents and elders of immigrant communities see little in their locale that befriends their worldview and as a result try to impose the beliefs, values and mores of the village they left on the new generation. This leads to further dislocation, distance and dissonance for the young who in trying to relate to their surroundings are caught between that and the mental surroundings their parents left but feel they have to impose. So, who do the new generation identify with?

Ties that bind

The tension between generations in migration is not new. Anyone who has observed international sports over the years can attest to that as generations of descendants of immigrants cheer for the teams of their parents or grandparents rather than the country of their birth. Not all of India’s supporters at Lords, the home of cricket in England, have come from Calcutta. Some of course also adopt the team of the land of their birth. Unfortunately, the depth of this generational dislocation, alienation and exclusion did not get the serious attention it should have got over the past half century, particularly in Europe. It took de-creative acts of terrorism worldwide to wake up to a conflict that immigrants were left to silently cope with over the years. In the past century how many radicals were cross-culturally grown?

But what these and other horrors also highlight is that immigrants and marginal groups were, and still are, dismissed as having nothing to contribute to the wider new societies they entered and settled in. Nevertheless, the painful truth is that these groups were the boxes that contained the seeds of future social, political and cultural developments.

On which the world rests

It is precisely because these groups were ignored over the years that John Reid, MP, Home Office Minister – justice minister – of the United Kingdom, and other political leaders internationally belatedly feel the need to understand the tensions in migration and do something constructive about integration generally but particularly in relation to ensuing generations. They need to accept that global policies affect the local soul.

Also, it should be kept in mind that for eighty-six percent of the world’s population, religion is important. Most of today’s immigrants think religion is important and they bring it with them to a Europe that is religiously bleached. Hopefully, both the old and the young can hear each other’s stories and will not have to transcend geography to form an identity. The hope is that they will feel at home where they are.

. . . Why have I waited

until your death

To know the earth

you were turning

Was Armenia,

the color of the fence

Your homage to Adana,

and your other complaints

over my own complaints

Were addressed

to your homesickness

Brought on by my English.

David Kherdian,

Armenian-American Poet