Fr Rufus Halley: A Tribute From His Little Brother

By John M. Halley

In July-August last year we published an article by Gaudencio B. Cardinal Rosales, Archbishop of Manila, about his friend ‘Pareng Rufus’, Columban Father Rufus Halley who was murdered in Lanao del Sur on 28 August 2001. Here John M. Halley writes about his older brother, whom he called ‘Rufie’, trying to come to terms with his death, and coming under the influence of Blessed Charles de Foucauld, who so inspired Father Rufus and his friend Cardinal Rosales.

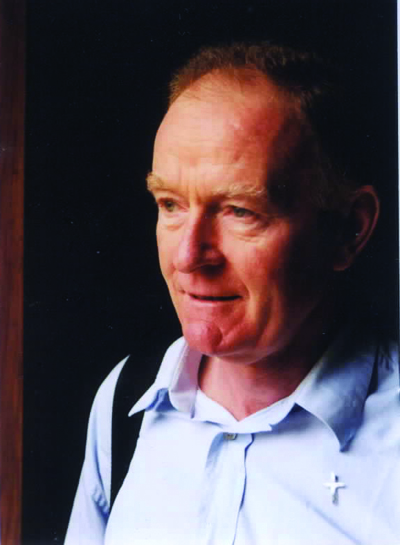

Wary of the special status and privileges sometimes given to Western people in parts of the Philippines, and inspired by the life and legacy of Charles de Foucauld, in the late 80's and early 90's Rufus worked in a Muslim grocery store as a shop assistant. This photo shows Panton (the shop owner), Rufus and members of Panton's family. I am seated on the right.

This is the seventh time that I have tried writing. Perhaps, if I had been able to cry when they were putting Rufie into the earth then I would be able to write this more easily. But my feelings were bottled up then, I couldn’t produce a single tear. They still are bottled up now. But I’m just going to write what comes into my head. To remind myself, I have entitled the file on my PC ‘Final.doc’.

My first vivid memory of Rufie is set in the kitchen of our home in Ireland and I was just six years old. He had a packet of cookies and he offered me one. I said ‘Thanks! Can I take two?’ This made him so angry that he snatched back the cookies and shouted at me ‘Now you won’t have any!’ I bawled with shame and fury but he didn’t care. Walking out of the kitchen, he went to his car and drove off, taking the cookies with him. I can still see his black Morris Minor, through the blur of the tears in my eyes, receding in the distance, impervious to my tears. Later that evening, we met again in the kitchen and I said ‘Could I please have a cookie, I promise I’ll only take one’ and he said ‘Sure, take two.’ I was reformed and so all was forgiven. Right or wrong, Rufus was always my inspiration.

Voice of reason

Fifteen years later he was recanting such a ‘medieval’ approach to correction. In those days we were both in England, I doing my PhD in engineering and he studying Islam in Birmingham. Meanwhile, I had scandalized my family by becoming an evangelical Christian at university. What I kept secret was that in London I had gone further and become involved with an extreme faction of evangelical Christianity, a cult interested only in proselytizing and which insisted everyone else was going to Hell. Under pressure, I agreed with them that all Catholics must go to Hell, including Rufus and the rest of my family. However, I couldn’t have believed it very seriously, since I continued to confide my secrets in Rufus and never in them, until one day I told him all about it. I said that as this cult had been hammering at my defenses they had gained somehow a handle on me. I remember Rufie said only this: ‘A handle? Now that’s not a good thing, when somebody has a handle on you, and wants to use it.’ Though I remain an evangelical Christian, from that moment I never let any grasping organization get a handle on my soul. And I told the cult to get stuffed.

Brotherly complements

Rufus had a different style to me. While I was always impressed with fancy things like glory and martyrdom (I’m still like that, a sucker for the epic picture), Rufie was more practical and preferred funny things. He was forever finding spiritual significance in boring everyday events. He introduced me to the story of Charles de Foucauld, the Frenchman who left Western society to live the life of the unseen Christ in a small village in Muslim North Africa. De Foucauld was killed by gunfire during the First World War. It is still a bit hazy as to why he was killed or by whom. Though de Foucauld was considered a failure in his lifetime, dying without any ‘converts’, he left a big impression on those he met. Today the little Brothers and Little Sisters of Charles de Foucauld are among the most vibrant orders in the Catholic Church, taking monastic vows but living ordinary lives alongside ordinary people. My brother was very excited at the thought of nuns and monks doing proper jobs in factories and sharing serious poverty. Not me. I imagined I could only cope with vows if I could look outside a monastery wall and see beautiful countryside. But a life of chastity in an urban wasteland? That was far too gritty for me. Over the years, Rufie continued to grow closer to the ideas of Charles de Foucauld and I continued to hide from them.

Visions of glory

But when we talked he didn’t entirely deny me the epic splendor I craved. One such moment was the evening he told me of his decision to work in Lanao del Sur. He would be in Marawi, ‘The Islamic City of Marawi’. He said his life would hitherto be dangerous. I was full of excitement. After all, I was young and young people like risky ventures. When he shared with me his vision of dialogue with Islam my enthusiasm grew. I had always had a romantic love of the religion of Mohammed, without ever having met a single Muslim. Maybe I read too much Arabian Nights when I was young! Finally, he told me about the spirituality of the Sufis, about Ibn El-Arabi who had so inspired the young Saladin and about Rabi’ah al Adawiyya who is said to have run through the streets of Baghdad wielding a firebrand and a bucket of water and threatening to burn heaven and drown Hell with these words:

Lord if I love you out of fear of Hell,

throw me into Hell.

And if I should love you in hope

of Paradise, deny me paradise.

And so he went to Marawi. And his gift for being as enthusiastic about everyday things and ordinary people’s preoccupations would make just as much an impression as his love of Islamic philosophy and mysticism, probably more. That was over 20 years ago.

Missing Rufie

Fr Rufus Halley

What I miss the most is his laughter. There is a kind of humor that thrives between close friends and which is utterly unique to that friendship. As the friendship develops so the dialogue grows with it and also the humor. Eventually you find new things which only that one person will understand and laugh at. Rufus began this process with his humorous view of world events and personalities and as we talked I began to develop a similar capacity. Between us there evolved an alternative history, a joke history of the world. Whenever we met or wrote letters to each other, we updated this history, adding new chapters and new jokes all the time. We spent many happy hours this way. Even now, I will often wake in the still dark hours of the morning inspired by some new connection. I know that only Rufus will get the joke. But Rufus is gone.

Finding peace

That Rufus was murdered is hard, and the hardest part is not knowing why he died or who really wanted him dead. You could call his death ‘martyrdom’ but there is nothing epic or glorious in it now. Sometimes, like in the ‘failed kidnap attempt’ theory, it seems like a sort of glorified accident. But if it really was like that, then my brother shared the death of so many of Mindanao with whom he shared his life. And so I, and others, have been compelled to share the indignity suffered by countless others in this world: to lose a dear one to injustice, to stupidity, to ignorance. As with the death of Charles de Foucauld, there are many times I have been tempted to believe that the sacrifice was pointless. I hear the call for justice and see it swallowed whole by conspiracies of silence and of fear. And this is a bitter pill for me to swallow.

‘Be still before the Lord and wait patiently for him’ (Psalm 37).

Where are those seeds of his work? Bless those robust, cheerful souls who see evidence sprouting all around them like a runaway garden! I haven’t been so lucky. But perhaps it is not the Plan for all of us to see the same things. And I have found some things, little things that start to wash away my bitterness. For example, the work of Charles de Foucauld no longer seems dull and, though it is not my vocation, I do not run from his ideas anymore. Instead they stir in me a longing like the Song of Songs does. Something else happened too. For many years before his death I had found churchgoing difficult. I was so trapped in self-righteousness that the company of other churchgoers was virtually unbearable for me. Then one day, I found myself in church again, and as I looked around I realized that I was no longer irritated by people. That was shortly after my brother’s death and so I see it as his parting gift to me. I believe that God will complete Rufus’ work, and those of us who are willing to wait and to pray may see some of it. But if this experience of mine is any guide, God’s work may be so quiet that we will see very little. Until one strange day we notice that the fear, the hatred, the darkness have moved on. No big bells, no music, just gone.

So Rufie, hear me! Whatever you are up to up there, spare a moment and pray for folks here to understand the meaning of these words: ‘Fools trust in themselves but the wise man puts his faith on solid ground’.