July-August 2000

A Miracle For Donnie

First of a series by Donnie Lama

It was a case of mistaken identity. I was at the wrong place at the wrong time. I was jailed by accident. But looking back on that fateful day I am certain that I was serving the right purpose of God.

It was a case of mistaken identity. I was at the wrong place at the wrong time. I was jailed by accident. But looking back on that fateful day I am certain that I was serving the right purpose of God.

The Saudi authorities were looking for a murderer. They though I was the murderer. But they found out later that I was not and I will never be the murderer. What they found in me instead after torture and maltreatment was a photo where I was holding up the body of Christ during communion service. The authorities did not find a gun or a knife or anything that would tie me to the killing incident. What they fund in my room was the reason why I was in jail – my hands holding the body of Lord.

I guess not so many are jailed because of picture. But I was. The picture was not an ordinary one, it was a picture of a man not acceptable in Saudi Arabia; that man is Jesus. He is the man present in the bread I was holding in that picture that put me in jail for one year and six months with 70 lashes.

A Filipino is Murdered

I returned to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia on October 5, 1995 to resume work in an airline company. Three days before my return a murder took place near our apartment. A Filipino hospital worker had been murdered. Vic Prodigalidad, a trusted friend who fetched me at the airport, updated me of the latest news. But I brushed the news aside. After all, I did not know the guy.

Meanwhile the dead man’s unidentified killer was now being tracked down by the Saudi authorities. They were looking for the murderer.

Midnight Knockings

I was renting an apartment in the City of Riyadh with two other Filipinos. One of whom happened to be an acquaintance of the boss of the dead Filipino. But did not know the implication of such an association until that fateful day of October 10, 1995. It was 11:00 in the evening. I was tied up doing my weekly laundry. I wanted to finish this weekly chore so that I could have a free weekend, Thursday and Fridays being the weekends in the desert kingdom. I was going to participate in a tennis tournament late Thursday afternoon. I wanted to have much rest as possible.

I was about to go to bed when I heard the loud pounding noise coming from the front door of my rented apartment. The people outside were pounding on the door so hard they almost knocked it down. They also tried to climb up the windows of the living room to get in. It was good that the windows were closed and had bars. I decided not open the door. Rey Barrera, my apartment, which did not have any window so we could at least hide ourselves from whoever it was outside.

My other apartment mate was not around. We had no idea who they were and their reason for being there. We recognized them, however, to be Saudis as they were speaking Arabic. But we did not understand of what was being said. We did not know that these were the policemen. We were terrified. We could only pray that the men outside would go away and leave us soon. I recited Psalm 91 with Barrera to comfort and remind us of God’s protection: Whoever goes to the Lord for safety, whoever remains under the protection of the Almighty, can say to him, “You are my defender and protector. You are my God; in You I trust” He will keep safe from all hidden dangers and from all deadly diseases.

The knocking continued until 2:00 am. Then it stooped. I was so nervous and mentally disturbed. I was not able to sleep the whole night.

In Case of a Raid

Early on the morning of October 11, Thursday, a weekend and therefore a no-work day, I took immediate and necessary precautions in case of a raid. I knew it was common occurrence in Saudi to have one’s house raided. You do not know just what might be used against you, no matter how innocent or neutral the object may be. The police will use anything as evidence. So very early in the morning, I cleaned my apartments and gathered all the religious stuff, e.g. Bibles, cassette tapes, videotapes, pamphlets which were the only things that I thought would implicate me. I brought them to the house of my friend Ronnie Germino who lived nearby. I kept all the rest of my things including the photo albums.

Instead of returning to my apartment, I went to Rey Sapnu’s house, another close friend of mine, just to spend my time with him for the whole day.

The Terrifying Raid

Barrera, who had an association with the boss of the murdered Filipino. Was so afraid for himself that he did not leave my side the whole day. Concerned with the safety of my apartment mate I thought of entrusting him for the night to another close friend, Rod Sitson, who runs an automotive shop.

Barrera, who had an association with the boss of the murdered Filipino. Was so afraid for himself that he did not leave my side the whole day. Concerned with the safety of my apartment mate I thought of entrusting him for the night to another close friend, Rod Sitson, who runs an automotive shop.

At around 5:00 pm, I went home alone to prepare for a tennis tournament. While I was talking with another friend on the phone, someone knocked on my front door. Without thinking I immediately opened the door.

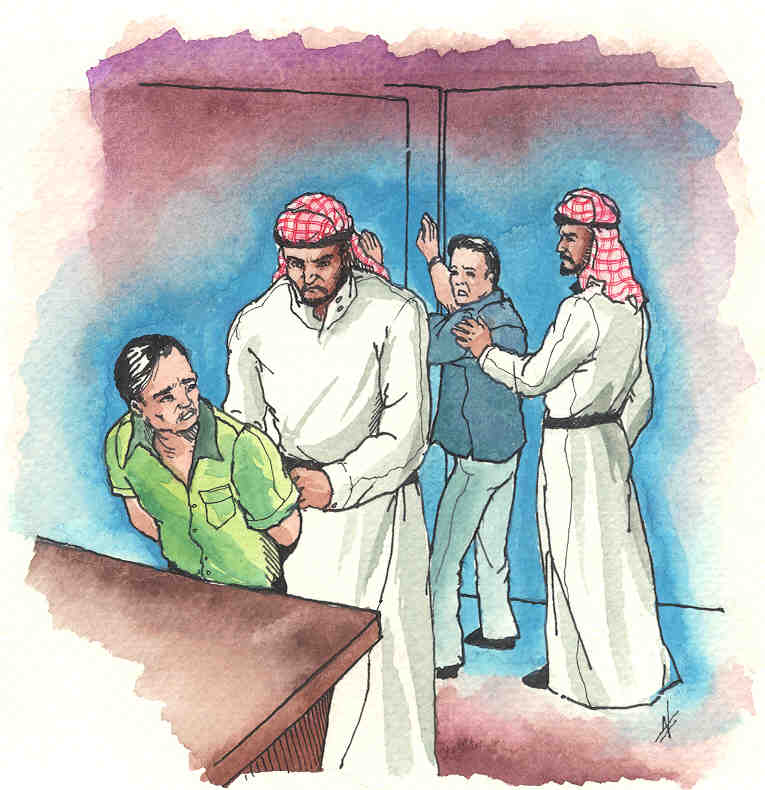

To my great surprise, five Saudis, six feet tall, wearing their Arab attire of white gowns rushed in. they were identifying themselves as policemen without any warning and asking question, they rushed to handcuff me with my hands at the back. As there was no explanation to why they were doing this, I protested, “No, you can’t handcuff me! What’s my violation? What’s the problem? Who are you? “You are the problem” shouted the group’s leader who turned out to be a Muttawah (the Saudi Religious Police). “Come with us to the police station. Give your explanations there.” I was caught between shock and confusion. They started beating me, kicking me and slapping me. Still, I protested while I was trying to pull away my hand. “You can’t do this!” They choked me so I could barely breathe I felt I was drowning. I felt terrible pain all over. “You are resisting arrest!” said the Muttawah as I kept on pulling my handcuffed hands which had by now begun to grow red and swollen. Then my other apartment mate, Mario who was resting in his room at the time, checked to see what the commotion was all about. He, too was immediately handcuffed and arrested, “Where is your other companion?” referring to Barrera who was actually the one they wanted to interrogate because of the latter’s association with the boss of the murdered Filipino. “He is not here,” we answered.

I could not believe what was happening. Then they started going through my personal belongings. They messed up the living room and the bedroom. They moved my furniture here and there, opened my cabinets, my drawers, ravaged though the neatly stocked clothes and other belongings. They began throwing things onto the floor whatever their hands got to hold of, unzipped bags. They found my photo albums and took the copies of my photographs and negatives. They said they were going to take them as evidence.

Then Mario and I were brought to the Al-Sulimaniyah Police Station with the things they had confiscated from my apartment including those albums.

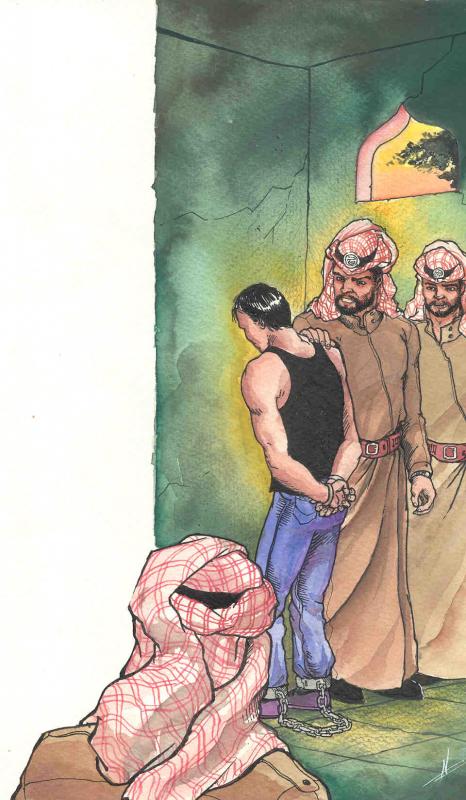

Torture and Interrogation in the Cell

At the Police Station, Mario and I were immediate separated from each other. It was 7:00 pm. I was asked to stand facing the wall still my hands were handcuffed for five hours. They also shackled my legs, so that I could barely move. When I moved ever slightly, the guards would immediately slap me so hard, kick and punch my body. Not content, they would also spit in my face. I felt as if my blood was surging to my head and I almost fainted. I thought I would pass out each time. Then they started interrogating me. “Your passport is fake!” they said. “No, it’s not. You can check it with the Immigration,” I answered back. “You know about the murder?" insisting of my knowledge about the murder. "I don’t know anything about it. I am telling you the truth.” Every time I answer, “Liar! Liar!” had been the reply with a stinging slap on both sides of my face.

A Miracle For Donnie Part II

First of a series by Donnie Lama

By Donnie Lama

...continuation

They thought I was a Priest

“You are a preacher for 15 years! You are a priest!” came the immediate accusation of the police upon seeing the picture and having known that I had been working in Saudi for the last 15 years. “No, I am not a priest.” I firmly replied. “You are a priest, where is your license?” the policemen would not change his conclusion. “I told you I am not a priest. I don’t have a license to show!" I wearily answered. Where are the people who are with you in the picture?” they interrogated further. “They are not here in Saudi anymore. The Filipinos went back to the Philippines. The Americans have returned to the States. Can't you see the difference how look in that picture and how I look now?” I defended myself. “No, you are a liar!” then my personal address book.

The Isolation Cell

Probably realizing that I was about to reach the limits of my tolerance level, having been physically abused for so long and not having eaten anything, the officer ordered that I be brought to an underground isolation cell, it was already 11pm. It was the worst place I could ever imagine to be in. The cell was a small, filthy and foul-smelling cubicle, very solid, dark, dirty and with so many cockroaches crawling all over the place. I started shivering at the terrifying coldness of the room. Its size was just a big enough to accommodate one person to lie down on the floor. That night, there were two of us licked up in one cell. There was no way we could stretch even for a little while to rest our weary feet and beaten bodies. I was feeling an attack of hypertension, my head and neck were heavy and I was aching all over. I felt as if my head would explode from all the pain I was experiencing.

The next day I was released because they had no concrete case against me.

The Terror Begins Again

The following day, a Saturday being the first working day of the week, I reported to the office, despite my beaten up condition. I told the incident to my Saudi boss and explained to him what happened to me. He assured me that there was nothing to worry about and and nothing to be afraid of as the company would try to do its best to help me out. “After all,” my boss said, “the interrogation is over.” I did not feel assured at all.

My instincts were right. The interrogation was not over. It was just the beginning. After a week, I got call from the police station. It was 2:00 in the afternoon. I requested my boss to talk to the police in Arabic. After putting down the phone, my boss informed me of the police invitation for me to go to the Police Station again. They will just ask me some questions. As I said goodbye to my boss that afternoon, my boss embraced me and sent me off with reassurance that everything will be fine. “You don’t need to worry about anything. You are a good man,” he said. As he advised me, I went to the police station in the evening even though I was wary of the intentions of the police and anxious for my life.

Before I reported to the police station, at around 7:00 pm, I drove my car heading to the house of my friend Vic Prodigalidad. His wife (Rose) cooked some scrambled eggs, hotdog and toasted bread but I refused to eat. I could not eat the food because I was very much disturbed. I requested Vic to accompany me to the police station. We arrived at 8:00 in the evening the police station. I told him to wait for me outside until 9pm. I said, “Vic, if I don’t come out of the Police Station, you will call immediately my boss to inform him that something has happened to me.”

Police Brutality

When I entered the police station, again, without any word spoken to me, I was immediately handcuffed and made to stand in one corner for three hours. The same ordeal was happening all over again – the endless questioning, the harassment, the brutality, the pain. I felt my world crumbling. This time, the three policemen with a bag they found in my apartment that afternoon of the raid were interrogating me. The bag contained bottles of perfume they claimed to belong to the murdered Filipino. I did not know anything about this and so I again denied the accusation of my involvement in the murder. The photo was again surfaced in the discussion. “What were you doing in this picture?” the police asked. “I told you, I was asked to pray. And that was in 1984, “I replied. “Liar! You are a priest! You have been preaching for 15 years!" came the insistent accusation. “I told you then and I am telling you now: I am not a priest,” again I replied. All the while, I was being slapped left and right, punched and kicked in the stomach and on my sides. As before they would bring me up and force me to stand only to be slapped and kicked again.

This Will Kill You

They wanted me to admit that I was a preacher or priest. “You see this rod?” the other policemen asked me holding in front of me one-meter long wooden stick which was able to draw a heavy line on my skin as it hit me. “This will kill you if you don’t admit that you are a priest!” they threatened. “I am not a priest,” I held on to my statement. “You are a priest! Your friend told us that you are a very religious person!” as it turned out, the police had interrogated again earlier that day Mario who had also been brought to the police station the previous week together with me. Mario thought he was defending me when he said, “Donnie is a good man. He is a very religious person.” But these were the very words that did me in. It convinced the Muttawah all the more that I was indeed a priest! I was brought to an isolation cell to spend the night there.

The Torture and Fatal Thumb Mark

For one week, the torture continued. Every night, they would pull me out of the isolation cell and interrogated me over and over again. The endless questioning, the same procedure, the slapping, the beating, the kicking. My body had turned bluish black and was completely swollen. I could barely move. Terrible pain. I could not tolerate it any longer. I was at my most vulnerable state when the police again pressured me to admit or else I would continue to be beaten. I was surprised when my interrogating officer said, “We will let you go if you sign this paper. If not, you may as well die here.” As I could no longer stand another beating I hastily attached my thumb mark on the document written in Arabic not knowing what it is I was signing. They sent me back to the isolation cell in anticipation for another week.

You Are My Refuge

Another seven days passed. I was down emotionally, besides my bad physical state. No one could visit me in the police station. Anyone who visited me would have been interrogated and imprisoned for 24 hours. I understood why my friends decided not to visit me. They knew they could face a 24 hour imprisonment with interrogation.

I was isolated in the real sense of the word. It was indeed solitary confinement for me. I had nothing except prayers to comfort me. During my lowest moments, they provided me with hope that everything was not doomed. I could only pray. I prayed the whole time. I would find myself saying to God: “Lord, help me go through this suffering. I don’t know your purpose for allowing this to happen to me. I only ask that you give me the strength to endure it.” I dreaded it when night time came. Again, I would recall Psalm 91: whoever goes to the Lord for safety, whoever remains under the protection of the Almighty, can say to Him, “You are my defender and protector. You are my God; in you I trust.” He will keep you safe from all hidden dangers and from all deadly disease. He will cover you with His wings; you will be safe in His care; His faithfulness will protect and defend you. You need not fear any dangers at night or sudden attacks during the day or the plagues that strike in the dark or the evils that kill in daylight.

These verses really ministered to me.

(To be continued in next issue)

Ask No Questions

By Sr. Jeanette Matela, SSpS

Happy Mistakes

I wanted to join the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary because my cousin who was with them was sent to Africa. But my spiritual director –an SVD – by mistake dropped my letter expressing my desire to enter the convent in the Holy Spirit convent Quezon City instead of the FMM convent in Tagaytay. When the reply and application forms came from the SSpS sister, I was surprised. I did not want to join them because I already knew them. I had been working as secretary to Mother Fidentina, SSpS, Principal of the Girls High School, University of San Carlos, Cebu City. Anyway I filled up the form and mailed it back to them. And the rest is history. I have no regrets.

Mission Fervour

The desire to the missions was always with me. It grew and grew as the years went by. Every time out superior came from Rome, I always found a way to talk to her and tell of my dream. Right after my first vows, I was appointed to Taiwan but I never got there. Since I had only a Bachelor’s degree, I was first sent to get a Master’s degree in Economics I was appointed Head of Commerce Department in the College of the Holy Spirit, Mendiola. The mission appointment to Taiwan fell into the waters. I was not discouraged. In 1973, my third year in College of the Holy Spirit, I got another mission appointment – this time to Ghana, West Africa. Actually, I had to choose: to finish my MBA studies or go the missions. I did not finish wiring my thesis, I went to the missions. God had given me my dream – to go to Africa like my FMM cousin. In Ghana, I worked as Accountant/Bursar in our mission hospital but on my free days I worked with the youth and women’s groups. Since I kept my mission fervour high and I learned to love the Ghanaian people, I had no difficulty adapting to the country and the people.

Needed in PNG

After four years in Ghana, I went back to the Philippines and I was assigned to Tarlac, then Laoag. On Christmas Eve 1980, I received a call from the Provincial Superior asking me if I am willing to go to a mission country again. The Divine Word Institute in PNG needed someone to head and teach in the Business Studies Department. Although deep down I wanted to say yes Right away, I tried to be generous. I suggested to her that sisters with the same qualifications that I have and who have not been in the missions should go for I have been in the missions already. But she told me that none of them liked to teach. So, on June 5, 1981, with another sister, I arrived in PNG and have been there since then. There were only eight students taking diploma in Business Studies in 1981; seven graduated in 1982. Besides being the head of the department, I taught all kinds of subjects from Typing to Accounting.

Agents of Change

In the beginning not knowing the culture and study habits of the students, I expected a lot form them. I gave reading assignments, expected a lively discussion of the materials the next meeting. When I started to ask question, I got no answers. I encouraged the students to ask questions, nothing was forthcoming. I was frustrated. A year later, when I attended an orientation course on Melanesian culture, my eyes were opened, in their culture, children are not supposed to ask questions from their elders. This is carried into the classroom. However, conscious of being an agent of change, I gradually encouraged students to ask questions as part of their learning process. As a result at present, the students in the degree level are more inquisitive than those at the matriculation level (Grade 11 to 12).

The Singsing

Speaking of culture, the Papua New Guineans are eager to preserve their cultural heritage. One of the means they use in though ‘singing’ where they really put on their traditional songs and dances. Different provinces hold cultural days, usually 2-3 days long, during which different tribes present their own singsing. It is against their traditional law for one tribe to use the singsing of another tribe. They even got to the extent that a non-member of a tribe is not allowed to join in their singsing. However, the law is not observed in schools when they hold a cultural day each year. Any students may join a group as long as he or she is able to produce the necessary bilas for the singsing. One cultural day in the Divine Word University, the Filipino group presented two folk dances. As I joined the group I thought about how one culture differs from the other but could still result in unity and friendship in a very special way.

Flashflood!

By Salve Nasol Pakson

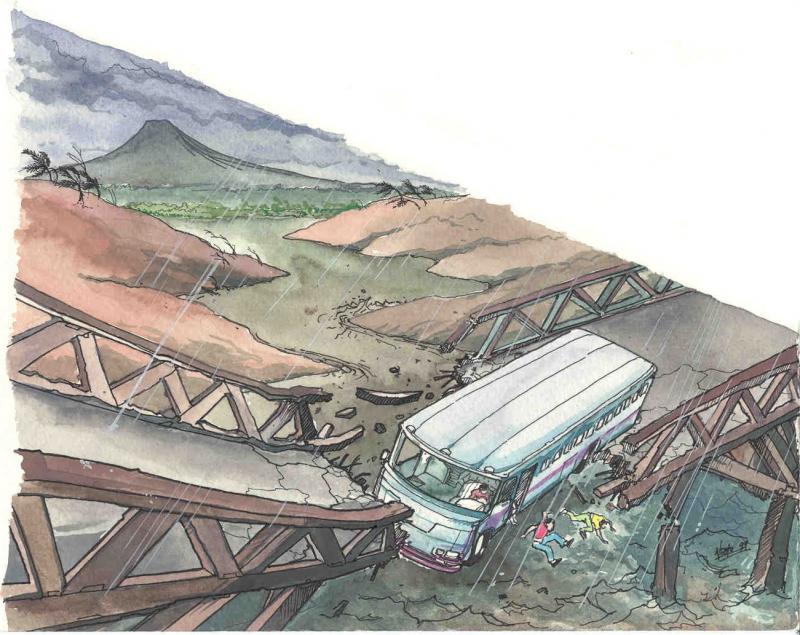

The clouds were forebodingly gray that day. But it didn’t bother me. I was just a kid – about five years old-and, all I knew, this was going to be another fun day with my Papa. He was a driver for ALATCO Pantranco Bus Company, daily plying the Ligao – Albay route surrounding scenic Mayon Volcano, winding along the seashore. Papa often brought me along because I suffered asthma and the breeze from the sea did wonders for my lungs.

So there I was, sitting next to Papa. Enjoying the breathtaking view while behind us his passengers-about 30 people or so-also gazed at majestic Mayon, remarking now and again how, indeed, so perfect is it cone! But as we cruised along, the clouds turned darker, rudely covering the volcano until, we could hardly see it anymore. And then, as we approached a bridge, a flashflood swooshed all around us, angrily pummeling the bridge, until to our horror, it collapsed!

Instinctively, Papa grabbed my hands as the bus plunged headlong into the raging torrent. The passengers shrieked in terror, some of them jumping out into the murky water, others just clinging tightly to the bus that now bode up and down like a little paper boat amid the furious waves. Then in the next second, it began to sink. I held on to Papa’s hands, as I felt the water fast rising up to my neck.

“Papa! Papa!” I screamed as my father desperately tried to keep me above water. I held tightly to him, but another wave hit us, separating us Papa swam back and grabbed my hands, again.

“Salve!” he cried, tightening his grip. “Hold on! Hold on!” As the rains continued to pour down on us, I held on to Papas hand but again, another wave hit us and I slipped out from his grasp. Again, Papa reached out to me. I caught his hands once more, even as the waters swooshed and swirled violently between us. Again, I slipped out and began to sink, the cold, dark waters beginning to claim me. In a last desperate plunge, Papa grabbed my hands again. I held on, as tightly as I could, but cruelly, the waters hit us once more. This time it seemed my arms began to freeze; my hands had turned so numb, I could no longer feel my father’s grip. I sank into the dark river, terror now enveloping me. I failed my arms desperately, trying to find my father’s hands in the dark. But alas, I couldn’t see anything anymore. I slipped into a black void, until the last thing I felt, I was being carried by waters – or by some Strong Force – away, away...

The next thing I knew, I was lying on a dry, warm bed. I was in my cousin’s house –alive! I turned out, people living near the riverbanks saw our bus plunge into the river and immediately set out to rescue the passengers. Miraculously, every single one of us, including my father was saved. I t happened that a cousin lived along the riverbanks and he was among the first to come to our rescue.

But the passengers blamed my father for the accident, charged him with negligence and brought him to court. The judge, however, ruled by father’s favor, stating that he wouldn’t have jeopardized his own daughter’s life.

Yes, my father wouldn’t have let me die. He struggled three times to save me. He would not have abandoned me – as my Father above never did. When my Papa could no longer hold me, I know, for sure, it was the Lord who took over and swiftly carried me to safety.

Salamat sa Kerygma

Letter To A Young Activist

By Thomas Merton

Extract from a letter to Jim Forest from the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, dated February 21, 1966; the full text is published in The Hidden Ground of Love, edited by William Shannon; New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1985.

Extract from a letter to Jim Forest from the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, dated February 21, 1966; the full text is published in The Hidden Ground of Love, edited by William Shannon; New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1985.

Jim Forest is now Editor of In Communion, the journal of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship.

Do not depend on the hope of results. When you are doing the sort of work you have taken on, essentially an apostolic work, you may have to face that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. And there too a great deal has to be gone through, as gradually you struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people. The range tends to narrow down, but it gets much more real. In the end, it is the reality of personal relationships that saves everything.

You are fed up with words, and I don’t blame you. I am nauseated by them sometimes. I am also to tell the truth, nauseated by ideals and with causes. This sounds like heresy, but I think you will understand what I mean. It is so easy to get engrossed with ideas and slogans and myths that in the end one is left hiding the bag, empty, with no trace of meaning left in it. And then the temptation is to yell louder than even in order to make the meaning be there again by magic. Going through this kind of reaction helps you to guard against this. Your system is complaining of too much verbalizing, and it is right.

...the big results are not in your hands or mine, but they suddenly happen, and we can share in them; but there is no point in building our lives on this personal satisfaction, which may be denied us and which after all is not that important.

The next step in the process is for you to see your own thinking about what you are doing is crucially important. You are probably striving to build yourself an identity in your work, out of your work and your witness. You are using it, so to speak, to protect yourself against nothingness, annihilation. That is not the right use of your work. All the good that you will do will come not from you but from the fact that you have allowed yourself, in the obedience of faith, to be used by God’s love. Think of this more and gradually you will be free from the need to prove yourself, and you can be more open to the power that will work through you without your knowing it.

The great thing after all is to live, not to pour your life in the service of a myth; and we turn the best things into myths. If you can get free from the domination of causes and just serve Christ truth, you will be able to do more and will be less crushed by the inevitable disappointments. Because I see nothing whatever in sight but much disappointments, frustrations and confusion...

The real hope, then, is not in something we think we can do, but in God who is making something and out of it in some way we cannot see. If we can do His will, we will be helping in this process. But we will not necessarily know all about it beforehand.... Enough ... it is at least a gesture...I will keep you in my prayers.

My Farewell

By Fr. Cresencio Suarin

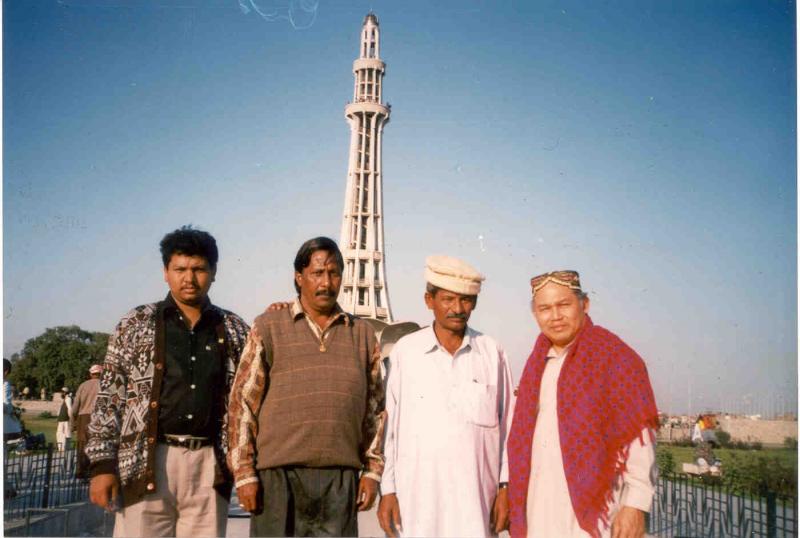

I arrived at Lahore International Airport via Karachi on April 30, 1993. As I went to the Baggage Claim Area to collect my belongings, to my surprise, my baggage could not be found. However I was assured that I would get it after a few days.

I went to the reception hall and saw the Philippine flag waved by the smiling Filipino lay missionaries (the late Pilar Tilos and Emma Pabera) together with Columban Fathers Tom, Paul and P. J. Kelly. They warmly welcomed me with their garlands.

The years have passed and not it is time to say farewell to my host country – Pakistan.

Mission Changed Me

My experience in Pakistan has changed my outlook in life, priesthood, mission, religion, culture and people. These valuable experiences have challenged me to plunge into the deep ocean knowing that people are basically good, hospitable and warm. I was able to go the unknown because I know that God is already there before I step in. my mission experiences were not all a bed of roses but mixture of joy and the sorrows, laughter and pains fulfillment and dissatisfactions.

First Difficulties

I guess every missionary has to undergo the process of purgation and Paschal Mystery before one is ready to unload and unclean the previous chapter of his life and to face the unavoidable struggle to learn the new realities. I struggled to learn the language of the people, adjust to their food (too much chill), Islamic culture, weather (can be very hot and cold), people (aggressive and demanding). These were my difficulties at he beginning of the first term.

Muslims All Around

As I worked in Pakistan which is 97% Muslim. I carried with me the unforgettable experiences of two of my brothers who were killed by Muslim rebels in Mindanao. God’s invitation to forgive our enemies is a perpetual challenge. The bias against the Muslims that says a good Muslim is a dead Muslim turned out to be totally false because my experiences with them has been fairly positive, enriching and life-giving. In fact it has lead me to healing, forgiveness and reconciliation. Since our house rectory is in the middle of Muslim community my daily living with them strengthens and solidifies my trust in them.

Sustaining Proverb

One proverb that I learned which sustained me to continue and work in Pakistan is the: Be patient because the fruit of patience is sweet. People taught me to be patient, understanding and considerate. These things happened especially during nicah – a wedding where the concerned party informed us that the nicah will be at 4:00p.m. But they arrived at the church at 7:00 p.m. it was also true of other schedules like meetings, invitations and programs in the parish. When they have celebrations (weddings, birthdays, funerals and other functions) the road will be closed be because they will use the road for their space. The motorists have to find their own way to reach their destinations. It takes a lot of patience to understand and accept the culture and the way they do their things which are different for mine, in Pakistan, being a violent society, I learned to trust God more that things will be fine despite the unavoidable violence and dangers that occurred everyday.

Things I Learned

My six years mission experience in Pakistan has become part of life. I would like to share some of my insights as priest and missionary assigned in a Muslim country:

(1) Fears, suspicions and prejudice are barriers to a meaningful and fruitful dialogue with our Muslim brother and sisters. I believe that true dialogue only comes when Christians and Muslims treat each one as equals. At present there is a big gap between Muslims and Christians.

(2) I received and learned more form people (Christian and Muslims) than what I gave.

(3) I need to learn and integrate these Asian religions Christianity, Islam, Hindu, Buddhism) which are very alive in Pakistan so that I can respect each religion and work towards a common vision for peace in Asia.

(4) For a diocesan priest to work in the missions, it is quite difficult compared to missionaries whose training is really for the missions.

(5) Pakistan means the land of pure/ it is in this sacred place that God invited me to purify my thoughts, actions, motivations, desires and plans so that I may experience and see God in every creature and event.

Once again I would like to reiterate my sincere thanks and gratitude for all who have helped and supported me to make my mission in Pakistan a memorable event.

Nigeria Is Alive

By Sr. Vilma Juaneza cm

Nigeria faces a serious political crisis at this time but daily life goes on. Sr. Vilma Juaneza finds joy and challenge in Nigeria vibrant Church.

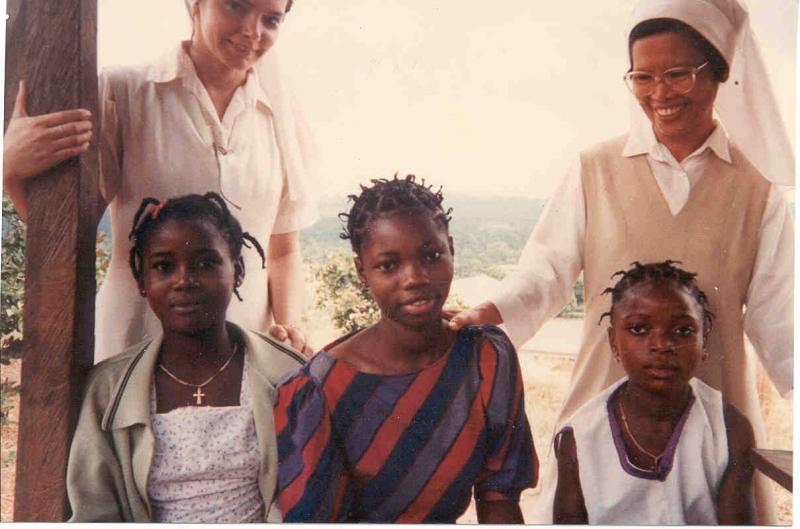

We have come to Nigeria to be a part of the Church’s work of evangelization as well as to share with them the riches of the Carmelite Spirituality. We believe that we can do this by first ‘forming’ young women who will work with their own people in the future. We therefore focus our attention on Formation. We arrived here on July 16, 1989, two of us from Iloilo. The following year another sister from Colombia joined us. That completes a trinity.

Filipino Connection

The Carmelite Fathers who started their foundation here in 1988 had been in the Philippines for several years especially Frs. Michael Fitzgerald and Francis Considine. They are a great support and consolation to us and almost always our topic of conversation in the Philippines. They are the first to inform us of the latest news from home. They have a good number of Nigerian postulants and novices.

Local Color

Our first year here has been a year of day-to-day surprises from the people we meet, the food we eat, the places we’re invited to and transactions made with the Nigerian. It’s exasperating but funny and entertaining at times. Have you seen a typewriter walking? on a woman’s head? or a wardrobe moving on two men’s head on a motorcycle? or a bishops blessing people using a mosquito sprayer? Sometimes at the Offertory on Sunday we see parade of farm products vegetable, fruits, grains, fowl, a rams and ever officers who dance to the rhythm of the drums.

Quality Not Quantity

Masses here, especially on Sundays, are well-attended whether in big cathedrals or in the classrooms in the villages. There are many local as well as international congregations here. But no Nigerian can ignore the Filipino charm, sense of humor, simplicity, hospitality and depth, if all we wanted was quantity of vacations our house would be overflowing by now; but quality is more important especially for the first group of Carmelite Missionaries. After many visits, interviews, letters, encounters and sharings, we admitted three young women to start the postulancy.

Nigerian Culture

Except for the old people in villages who have not gone to school, everybody here understands English. That facilitates our mobility, but we believe we can be more effective if we can learn the language. That’s not the only limitation we have. There’s a lot more to know about the Nigerian culture and history, people and languages which are different in every tribe.

Nigeria was Christianized very slowly during the last 100 years but got there independence only 30 years ago. The presence of Islam is powerful and so also traditional animist religion.

A Great Challenge

There’s no dull moment in Nigeria. Every moment is a call for creativity, for celebration, for gathering, for prayer, for involvement, for conversation. So, too, a whole range of areas of Church life calls for inculturation. This is a great challenge for us; this same challenge is posed to the Nigerians. Meantime, let's start with our young Nigerian women who choose to be a part this beautiful work of evangelization. As we form them we are also formed by them, and in the process we experience unity in diversity in a way that gives meaning to our lives.

Oasis In The Desert

By Sr. Mary Ignatius Aquino osb

Sister Mary Ignatius Aquino was appointed to the difficult task of Novice Directress in Ndanda Priory, Tanzania. Here she shares her reflection.

Tanzania is a poor country on the west coast of Africa but it is rich in faith. So what better place for the ancient order of St. Benedict to come and set up monasteries as havens of prayer, peace and love. Sr. Mary Ignatius Aquino, a Filipino Benedictine, has been appointed to the Ndanda priority in Tanzania as Novice Mistress. Her job is to introduce young Nigerian women to the spiritual life and equip them with the convictions that will help them to persevere in their journey to holiness.

Ndanda Priory

The Ndanda Priory is composed of mostly German Sisters, a few Swiss, some Tanzanian junior Sisters and few from countries like Poland, Philippines and the United States. The international character of our congregation is enriching and challenging. It’s great to see the perseverance of our Sisters in bearing with their old age and sickness, in carrying out and seeing through their big hospital and leprosarium apostolates and staying until death in areas where they are sent. Living the elderly, the middle-aged and the young provided me with a complete cycle of human life’s experience.

Burning Needs

One of the burning needs of the Ndanda’s Priory is the formation of young Tanzanian women who want to join our congregation. Right now, there are four Novices, three postulants and six aspirants. They came from the different regions of Tanzania.

Novice Directress

As Novice Directress, I give lessons in consecrated life and the rule of St. Benedict. I also give regular spiritual direction and formative counseling to the Novices and Postulants. Accompanying these young Nigerian women in their religious vacation brought me face to face with God, with others and with myself.

God as Formator

As a Formator in Africa, I’ve started to learn again like a child. In my relationship with the Formandees, I had to trust that their motivations are good and I had to trust that it is our Lord who called us to live in the Community. Above all, I had to trust that God is the Formator and it is to Him that each one had to render an account.

I love where I am for I believe that it is God who sent me. Like St. Ignatius of Loyola, I pray: “Your love and your grace are enough for me.” I am happy to be a pat of the history of our first mission country founded by Fr. Andreas Amrhein, osb and to rebuilt and develop or mission in Tanzania. May our Holy Father St. Benedict continue to intercede for us that our monasteries my become oases in the desert where anyone could find peace and delight in the Lord.

Return To The Killing Fields

By Gee-Gee O. Torres

We sent our Assistant Editor, Gee-Gee Torres, to Cambodia to visit the six Filipino congregations in that Southeast Asian country and to see how they were doing. Here she shares with us in the first of several articles part of her own missionary experience. (Ed.)

Everytime I hear the word Cambodia, a particular film comes to mind. So when Editor, Fr. Niall O’Brian, told me that Cambodia was my next Misyon assignment, I remembered myself sitting on the floor, watching that film in our Audio-Visual Room in high school at St. Scholastica’s Bacolod. The movie horrified me. I wanted to leave but my classmates and I had to submit a movie review the next day. So I forced myself to stay on but I pretended to myself that I was not there. However, no matter how hard I tried, I could still see the anguish on the faces of people-hundreds and thousands of them being herded along the roads of Cambodia. The children looked scared and confused. I could hear people crying for help, screaming in pain, pleading for their lives. That movie was The Killing Fields.

Boarding TG Flight 626

Although I felt apprehensive, I suppressed my fears and boarded TG flight 626 bound for Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. I was flying via Thailand. After 90 minutes I was already gazing out at Pochentong Airport. I panicked a little. I couldn’t find Bro. Raddie Lagaya, sdb at the airport. I had no idea what he looked like. I just knew his name from one of the articles I had proof-read in the office. I got to an airport phone and called up their house but Fr. John Visser, their Superior, said he had left some 30 minutes earlier to collect me. I went out of the airport again, made a wild guess and approached a man who looked like a Filipino. Ooopps, sorry, he wasn’t Bro. Raddie. He didn’t speak Tagalog or English, only Khmer. Fr. John said Bro. Raddie would be wearing eyeglasses and looks like President Erap. I tried my luck again. This time I spotted somebody who looked like President Erap, though a bit shorter. He turned out to be Bro. Raddie and together we headed of to the Salesian Sister’s House, which he said was going to be homebase. On the way, he gave me a brief run through of tragic history of Cambodia.

The Tragic History of Cambodia

Cambodia is part of what used to be called French Indo-China, an integral part of Southeast Asia with an ancient culture symbolized by the famous Angkor Wat period of colonial expansion the French moved into this part of Asia – hence the name French Indo-China. After the Second World War most of these places fought anti-colonial wars of liberation. The French left reluctantly and the Communists naturally got a foothold. During the Vietnam War Cambodia got sucked into the conflict. The Americans bombed Cambodia mercilessly. Somehow or other that gave a chance for the famous Pol Pot, the Stalin of Southeast Asia, to take over. He introduced an ideological Communist regime, the like of which will go down in history for its unbelievable brutality. It was he who instigated the killing fields which had so revolted me when I was a student. Cambodia at this stage went though an unspeakable nightmare of horror. It was only after the Berlin Wall came down and the tide of Communism receded in so many countries that Cambodia opened up once again to the world.

Land of Suffering

Cambodia can be called a land of suffering. Today it lies prostrate after the nightmare years of the Pol Pot Regime. Many effects of the wars are still around – diseases like TB from lack of food and AIDS from the uncontrolled tourist sextrade and, of course, the whole story of landmines. Cambodia is filled with landmines, which still so many women and children. It was to this Cambodia that the Missionaries of Charity, the Sisters of Mother Teresa, decided to go.

Missionaries of Charity

Among the Missionaries of Charity in Cambodia are two Filipino sisters. They are Sr. Clarissa and Sr. Vita. Sr. Clarissa has been on mission in Cambodia since 1992 while Sr. Vita has just been transferred to Cambodia from Taiwan where she had worked for 22 years (Taiwan, HongKong and Macau). The Missionaries of Charity take care of the poorest of the poor. In Cambodia, they have TB and HIV Centers, a feeding center for malnourished and sickly children and a free-clinic every Saturday.

I went with Sr. Clarissa and her partner, Sr. Shooli from Bangladesh, on their regular visit to their TB and HIV patients living along the riverbanks of Phnom Penh. Many people there are literally floating on the water in boathouses. I suppose there is no room on the land. Other houses are on stilts like you see among Badjaos in Mindanao.

Sr. Clarissa told me that just recently she almost got drowned. She was on her way to visit one of the HIV patients who lived in one of the houses hanging over the water. She crossed a narrow wooden bridge going to the house of the patient. When she was halfway across, the bridge collapsed and down she went into the water. “I thought it was my end,” I managed to stay float, but then I began to sink. Sr. Shooli called for help. She knew I couldn’t swim. While I was struggling in the filthy, stagnant water, I told myself if this is God’s will, let it be. But when, after what seemed to me in eternity. I was finally rescued, I began to feel scared. I know God loves me and sometimes He makes fun of me. This time He really did it well,” said Sr. Clarissa smiling.

Sr. Vita mc

Sr. Vita, on the other hand, is assigned in their Home of Peace where they look after AIDS patients with terminal cases; these are patients who have been refused by the hospitals and, worse, who have been rejected by their family. She said that their work is very demanding. Patients become irritable. They would even throw things at the Sisters. “They don’t mean to hurt us. If you listen to their deepest desire, they just want to be loved. They are looking for attention and affection. They don't want to be alone because they are afraid to die. We do our best to make them feel that we care. Sometimes a husband and a wife are both there. It’s painful to see them go especially whey they have children to leave behind,” said Sr. Vita.

“What keeps you going, Sister, in this tough job?” I asked. “I always think of words of Mother Teresa: Peace begins with a smile. So even if life here in Cambodia is difficult, I find it fulfilling. I do my work with a smile.”

Cambodia’s Concentration Camp

Later I got the courage to visit the actual torture chamber of the Khmer Rouge in the south of the city, Teul Sleng. Before they used it as a torture chamber, it had been a school. But today it is a frightening reminder of the horrors brought on by the Pol Pot regime. As I entered the gate, I wanted to step back. I saw myself again sitting on the floor in the Audio-Visual Room. I wasn’t too sure if I was brave enough now to see this reality – Cambodia’s biggest torture chamber and prison. But I had to confront my fears and this was the time. So I walked through the gate. In one of the exhibition rooms, I saw the displayed hundreds of photographs of Cambodians facing torture and those who had been tortured. There were also photographs of foreigners who somehow ended up their as either innocent victims or as suspected CIA agents. These were the people I had seen when I was watching that movie, The Killing Fields, many years ago. Now I was almost touching the reality. After a while I couldn’t stand anymore the macabre atmosphere which reeked of death. I had to cut short of my ‘pilgrimage’.

If until now I cannot get over these feelings, how much more so the people of Cambodia? They must still feel these wounds. And when I reflect about what our Filipino Missionaries are doing in Cambodia, I realize that it is these wounds they are helping to heal.

Room For One More At The Table Of Life

By Sr. Jazmin Peralta ssc

The new family life poster that came recently was very good and meaningful. It is really captured what every little helpless human being inside the womb of all expectant mothers would wish to say: “Mom, I too want a birthday.” I could imagine how that tiny, little creature would hope to see the light of day and celebrate a birthday.

Stressful But Exciting Work

My work with unwed mothers has been a very stressful but exiting experience. Stressful because I am not a trained nurse and I have no idea abut child care, but exciting because I experience the same anxiety and expectation these expectant mothers do as I journey with them. Indeed it is still a blessing and assort of miracle that in today’s Korea, where abortion is convenient and common, there are still many who would choose to give these unplanned babies their birthdays.

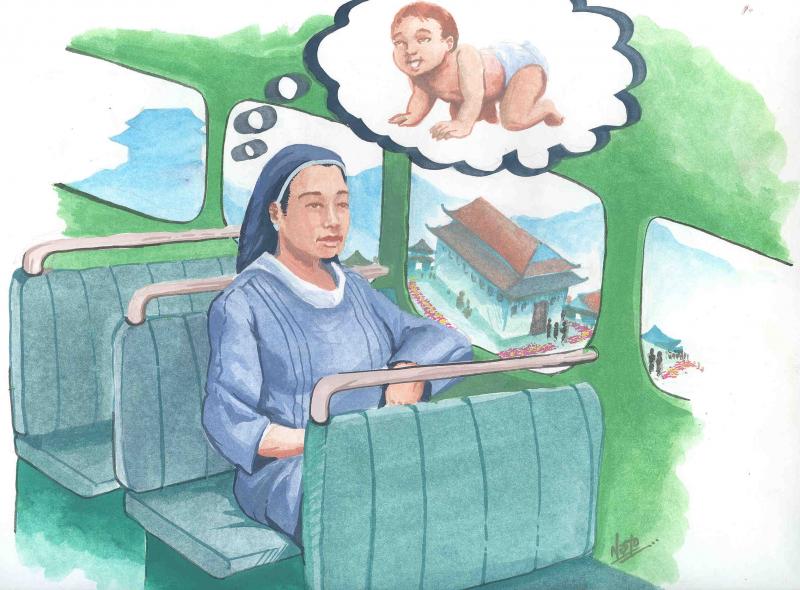

Sparing One Life

I remember an incident when I have to travel to Kwangju to collect a girl who was seven moths pregnant. She was admitted by her mother to a hospital for an abortion so she could graduate for high school in the next two weeks. The nurses in the hospital, who were Catholics, sere so worried that hey told a Korean Sister, who visits the hospital weekly, about it. When the Sister heard about it she got in touch with us immediately. I left, boarded a bus and wondered whether the girl would still be there when I got o Kwangju. I usually get sick when I travel by bus but that morning I was so preoccupied I didn’t get sick. I wanted to go there as fast as I could because she was scheduled to have the abortion that very morning. Along my way, I prayed to God that at least one more life would be spared and one more child would have the joy of being welcomed by the beauty of life.

In Due Season

The more I learn abut the function of the human body and how the tiny cell develops into a human being, the more I am in awe at the mystery and richness of life. When I imagine an aborted baby I see a picture of a premature fruit that has been forcefully plucked from the stem. So the baby, likewise, is forcefully plucked from the uterus. The baby should be delivered in due season life a ripe fruit that will just naturally fall from the stem.

I arrived on time. I was able to see and talk with the girl in Kwangju and after a few months she gave birth to a healthy baby boy. She had the baby adopted. But she was the only girl who wanted to see her baby, most mothers don’t even look at their babies before giving it away for adoption.

The Gift of Life

I still do believe in miracles. So even if a lot of women here in Korea go for adoption. I know that there are still many others who understand the wonders of God’s call to life, enter a difficult but rewarding path of family planning and who avoid the spiritual and physical trauma of abortion. As a result, many babies can bask in the beautiful mystery of life-the most precious girt of God to us.

The Noble Aetas

An interview with Donal O’ Dea, ssc

They live in the Northern Philippines and have retained their own way of life for two thousand years despite many attempts to make them change. The catastrophic eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 presented a new challenge to their existence.

An interview with Fr. Donal O’ Dea, ssc who works with them.

Q. Where exactly is the area in which you presently work in the Philippines?

A. it is the Province of Zambales, 150 miles north to Manila. I was asked by the bishop and the Columbans to do some work with the Aetas people who live in the region.

Q. Could you give a bit of background on the Aetas?

A. One theory is that they came for Papua New Guinea, are related to the Australian Aborigines and came via Borneo into the Philippines at least 2000 years ago. They first settled along the shoreline but eventually they were pushed up into the mountains.

Q. Physically, are they different form the majority of the Filipino people?

A. Yes. Filipinos in general share characteristics with the people of Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. The Aetas are also known as Negritos because they are black. On average they are smaller, have kinky hair and features that are quite different. They have their own language. Apart from this there are other important differences. They, unlike all the other ethnic groups, were not conquered by the Spaniards. The vast majority of the other groups in the Philippines were integrated into the colonial system. In the South of the Philippines there were attempts by the Muslim groups to absorb the Aetas. In the Northern area where I work they slowly moved up into the hills. They held on their own culture, language and traditions. They did not accept Christianity.

Q. Since you first went to the Philippines in 1952 the population has gone form 17 million to about 75 million. Does that mean that many ethnic groups are being swallowed up by this population explosion?

A. their land is being swallowed up first of all. That is the principal causes of the conflict in the Southern Philippines. In some provinces ethnic groups that were thriving 50 yeas ago have totally vanished.

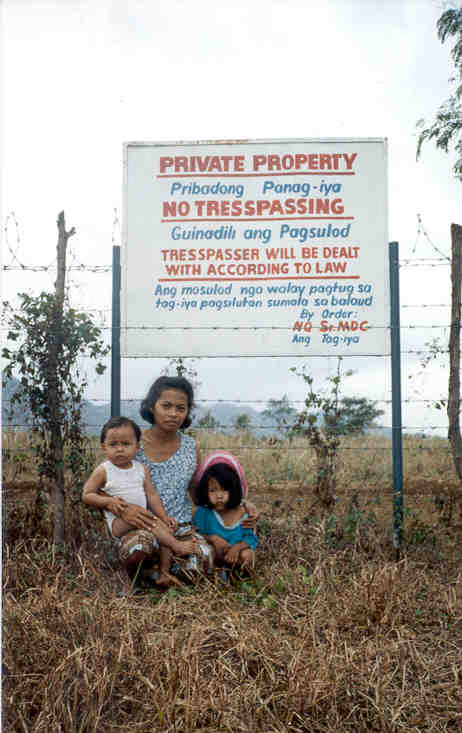

Q. Some people would no doubt argue that it is unfair that people like the Aetas should want to hold on to large tracks of land while there is such an increase in the population and in the need people have for land.

A. People are not allowed to ask similar questions about the big multinational fruit producers or mining corporations, or the tourist or golf complexes. Big companies want the land to increase their profits. All the Aetas are looking for is enough land to live on. Unfortunately they have no legal claim to the land on which they have lived for the past 2, 000 years. It belongs to the State. They want to be recognized and have a right to some land. A major threat at the moment is mining. A powerful mining company can get a concession for an area the size of the combined country. They are given all the mineral rights to that area and the tribal people, whose home it has been for centuries, are given no voice in what happens.

Q. The philosophy of the Aetas is presumably very different to that of the mining corporations?

A. Yes, the only thing in common is that they both somewhat nomadic. The Aetas plant bananas and sweet potatoes. They shoot wild pigs and live mainly on fruits and various types of vegetables. They fish in the rivers. Groups of six to nine families plant rice and corn in the hills. They don’t believe in planting anymore than they need. Some occasionally come down to cost and take jobs during the harvest. They can live very simply on a low diet. Their health, sanitation and literacy is very poor. Very few of the Aetas would be considered practicing Catholics. It was only in the sixties that Christian communities were organized in the area.

Q. They live at the foot of Mt. Pinatubo. How serious for them was the eruption of the volcano in 1991?

A. It was a major disaster. Thousands of hectares of their land was covered by eleven billion cubic metres of volcanic ash which has now hardened. The Government did make an effort to help them by providing some resettlement camps. Some of the people moved away to other areas. They were being swamped by people with good intentions. They became something of a curiosity. One of the good things was that the Aetas became known. Suddenly the public realized that there were up to 10, 000 of them and that they needed help urgently. But apart from the short-term help the fundamental question was how would they survive as a people?

Q. When did you get involved with the Aetas?

A. About five years ago. I was the last Columban who had worked in their area in the hills. I knew a lot of the people who had been working with them. I knew that they were in need. They have been devastated and scattered by the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. Around that time the bishop asked for a Columban to work with them. I offered to go.

Q. What did you do at the start?

A. At the beginning there were questions to be answered. Where were they now and how many of them were left in the area? Who was with them? What were their immediate needs and long-term needs now that they had lost their original base? What, in practical terms, could we do to help them?

Q. At the beginning what did you see as the pressing needs?

A. At this stage many of them were reduced to begging. The needs were survival, food, work, land to till. We tried to gather solid information and identify the natural leaders. We also checked on the aid they were entitled to from the Government. We took steps to ensure that the rights of the remaining people were respected, that they would not be pushed of f their land. The local Church has committed itself to the defense of the Aetas. It defends their claim to their ancestral land. It has helped them to preserve tier culture, tradition, language and even religious beliefs. It has tried to make the people of the Philippines more aware of the rights of the indigenous peoples in general, those who once owned the land and have now been herded into its remote corners.

Q. Do you believe that there is something worth preserving there?

A. Any language that is unique is worth preserving. It is an extraordinary vehicle of expression. They have their music, their dances, they feel at home with themselves and their environment. Their ability to live simply in sparse situations challenges our voracious consumerism. Enough is enough with them. They share everything they have. These are a people who have survived simply and admirably for two thousand years.

Q. When you look back over the past five yeas, has anything been achieved?

A. Some things have been achieved. The Aetas are now aware that they are not alone. Others are concerned. We have helped them to articulate their needs, even though often these haven’t been answered. Programmes have been initiated with quite a bit of support from NGOs and the Church. We have backed them right up to Congress in their struggles to get rights to their land.

Q. The history of work with indigenous peoples has many examples of paternalism and damage dome by well-meaning people. Have you ever been accused of that?

A. Paternalism is the simplest thing in the world to get into. It is very difficult to avoid. One of the first dangers is that you try too hard to protect people from outside influence. If you worked to develop leaders you must let them lead, let them make mistakes. This can be hard if you think in terms of money or efficiency. They managed to get on without us in the past. We have to learn only to come into the picture when we are needed.

Q. You were a parish priest for most of your life. How did you adapt to this very different approach?

A. At first it was a pretty difficult change. I didn’t realize it until I left the parish. There I knew everything that had to be done. Suddenly, in a sense, I was a free man but one ho was no longer clear on what he should do. I had been asked to reach out to the Aetas – brother s and sisters in need but also people who had little interest in things one normally associated with the ministry of a priest. I was sent to be with them but also to be respectful of their ways. It was a mission that was very different for me but one which, over the last few years, has stretched the horizons of my own understanding of what the Christian message is all about. (The Far East)

The ‘First Time Ever’ Altar Boy

By Fr. Paul Richardson ssc

My father was a bus driver in Boston and always worked the earliest possible shift, so he always got up early. It was his job to drive the first of the daytime busses out of the bus company garage at 6:30 in the morning. (There were two nighttime busses that drove around our town in apposite directions all night.) My father got up at 5:30 in the morning and left the house for work at 6:00 o’clock. Between the opening and closing of doors and other related noises, I was always wide awake when he left the house. And since I didn’t have to be at school until 8:15, I became very religious. The morning Mass on weekdays in our parish was 6:30 a.m. and I started going to Mass every day. The church was only ten minutes away from our house.

At that early hour, there weren’t too many people at the Mass – the celebrant, of course and one or two altar boys; a few elderly and faithful ladies; me and the back up organist called Mrs. Maguire (she was a good organist but a real screecher of a singer); and Miss Brennan, whose brother was a retired priest of the Archdiocese and who looked after the vestments and the altar. Miss Brennan also trained the altar boys.

For years, Miss Brennan had tried to get me to become an altar boy, but until the beginning of the war in 1939, we lived too far away from the Church for me to serve and Mass still get to school on time. But then, one morning in 1945, Miss Brennan got her wish. There was a Month’s Mind Mass with the ready organ notes and Mrs. Maguire’s slaughtering of the Gregorian music and the priest’s routine (and slightly) rushed rendition of the singing parts in the missal. The Mass was all over in record time. I watched the priest and the altar boy go off the altar. It was too early to go home. The church was very quite. I knelt down again and closed my eyes. A minute or so later, someone tapped me on the shoulder. It was Miss Brennan.

“Paul,” she said (everyone in the town seemed to know my name since my father was a Damn Yankee...) “Paul, she said, “our regular altar boy had to go home to wake up his two brothers for school and we have a visiting priest in the sacristy waiting to say Mass. I want you to be his altar boy.”

“But, Miss Brennan,” I objected. “I don’t know any of the Latin prayers.”

Don’t worry,” Miss Brennan answered. ‘I’ll say all of the responses for you. All you have to do is go ahead of Father when he goes to the side altar, take his biretta when he hands it to you and kneel down. When he puts his hand on the altar, go up and move the book to the other side. When he takes the veil off the chalice, bring him the wine and water and then wash his hands. Ring the bell at the consecration, bring the wine and water again after Father’s communion and that’s it.”

I was trapped.

After Mass, I preceded the priest into the sacristy. He thanked me and congratulated me. Miss Brennan had told him before and that it was the first well,” he said. “What grade are you in school?”

“The eight grade,” I said. “Miss Moran is my teacher.”

The priest smiled. “My name is Fr. Cogan,” he said. “My sister is Mary Moran’s mother. Your “Miss Moran’ is my niece.” And, he smiled again. “Why don’t you come across to the rectory and we’ll get some breakfast?”

“Father, I’m sorry,” I replied, “but I cant. I might be late for school and Miss Moran wouldn’t like that.”

The priest left the sacristy. “Where does Fr. Cogan work?” I asked Miss Brennan.

“In the Philippines,” she answered. “He was there all during the war and he’s on his way home to Ireland for vacation. He came this way in order to visit his sister and your Miss Moran. Fr. Cogan is a missionary priest.”

I smiled and said nothing. I knew many of the altar boys and I had never heard even once that one of them had been invited over to the rectory for breakfast. They always had to eat at home. “But maybe” I thought, “that’s because they’re secular priest (my father used to call them ‘circular priests’ which was true) and not missionaries...” Then and there, I decided that, if I ever became a priest, I would become a missionary and not a ‘circular’ priest. The following week a magazine came from a missionary group. I clipped out the coupon and mailed it in. After a visit from a Columban priest, I was accepted for the minor seminary at Silver Creek, New York.

But, there’s more.

Like all other missionary organizations, the Columbans in Boston, Massachusetts (U.S.A.) always have annual ‘field day’ in order to raise money for their members on the missions. That year, the field day in Boston took place one month before I was scheduled to Silver Creek, New York, and I persuaded my father to take me there. We drove in his car, and about twenty yards from the entrance to the parking lot, he stopped.

“What's wrong?” I asked. “The parking lot is up there.”

“I know,” my father answered. “But, get out of the car and come with me...”

We got out of the car and walked towards the front balcony of the estate house where the Columban priests lived. There were two or three people seated on the balcony and one of them – a gentleman – rushed down the steps and greeted my father.

“Les...! It must be years...” The man was a Mr. Moran who had been in the army with my father in 1918. We went up on the porch. My father introduced me to Mrs. Moran.

“Oh, yes,” she said, “you’re the Paul who was in Mary’s class last year. And you’re the one who served Fr. Gary’s Mass when he came through to visit us two months ago!

I smiled. Mr. Moran was Fr. Gary Cogan’s brother-in-law and Mrs. Moran was Miss Moran’s mother. It was the first time that I knew that Fr. Cogan was a Columban priest! And, of course, a missionary.

Those Who Make Reform Impossible...

By Sean Farrell, Columban lay missionary

Chiquita Redosendo, a 27-year –old mother of two, comes from the small village of San Vicente, Bukidnon. I met her when she, alongside her companions, took the drastic step of going on a hunger strike to protest what has been happening to them. This was in October 1997 but their story begins long before this.

Dream Fulfilled

Chiquita is tribal and under the Government Agrarian Reform Programme she applied for land alongside her husband Ronaldo. She was told that she was qualified under this program. Along with a group of other tribal, landless farmers who formed a co-op called Mapalad, the government awarded them certificates of ‘land ownership’ for a property of 144 hectares belonging to the industrialist Norberto Quisumbing. Their co-op had 137 members, guaranteeing each family would receive about 1 hectare of prime agricultural land right in the very village that they come from. This was in 1995 and it seemed as if a dream had come true for them. They were finally to get the chance to raise their two children in their own simple house and on a small piece of land that they could call their own.

However over the weeks, months and years that have passed, their dream has turned into a nightmare. Despite having been declared the legal holders of the land Chiquita and her companions have been kept from farming their land by force delay, armed thugs and political corruption.

Surprise Move

Their story is one of oppression and injustice. Firstly, the landlord got the local politicians on his side. They together pressurized the Office of the President to take the agricultural land form the farmers and award it back to them for industrial use. Despite the existence of the local government law against his procedure, President Ramos’ Executive Secretary Ruben Torres reversed the land decision and gave the land that rightly belonged to the tribal farmers back to the land owner. Chiquita could not believe what was happening to her dream: “My heart was so pained – and I felt so put down and oppressed by the local government officials especially out local mayor and out local governor here in Bukidnon. Not only would they not help us at all, but hey continually aided those who wanted to keep us off our land.”

Driven Off

Out of frustration with the local and national political corruption that they were experiencing the farmers decided to enter their property and exert their rights to the land. Chiquita and Ronaldo entered the land with their Mapalad companions. Why shouldn’t they, they said. After all, it had been awarded to them. They set up their tents and began cleaning grasses. Their work only lasted 2 days. Then they realized the strength of those opposed to them. A private army led by Col. Noble and employed by Mr. Quisumbing arrived at the site. They fired weapons, burned tents and use a herd of carabao to drive the farmers from their land. The message had been very clear. The farmers sat outside the land and watched armed thugs patrolling the ground where their crops should be growing.

Hunger Strike

They however did not retaliate to the obvious intimidation and treats of violence and death. They made many appeals and petitions even to President Ramos himself. They got nowhere. Finally a decision was made to make a final gesture of how unjust the treatment of them had been. They went on a hunger strike. For 30 days, 18 strikers stayed in makeshift tens on the streets of Manila and Cagayan de Oro. I myself will never forget that moth or as long as I live. The courage and bravery of these people was incredible. They fought for life from the very jaws of death. Those of us who supported them at this time saw them lose weight, suffer headaches, get sick and feel terrible stomach pains. We saw a number of the strikers like Tessie collapse from the lack of food and the sheer exhaustion of their trials.

Active Nonviolence Succeeds

On day 14 of the strike, the President announced that he would make a decision in six days. It was clear that the national media attention had turned their case from just another problem in the mountains to a national issue. When the six days passed and no decision was made the farmers resumed the hunger strike, swearing they would not yield until they got what was rightfully theirs. Finally, a decision was made. President Ramos awarded 100 hectares to the Mapalad farmers and 44 hectares to Mr. Quisumbing. He called it ‘win win’ solution. Chiquita still has strong memories of that time: “The time of the hunger strike was really terrible. I felt such hunger and such terrible weakness. We waited and suffered for the decision of President Ramos and we struggled onwards, thanks to the many people who supported us because we stood so strong, we won back our land.”

Great Joy

When the strikers returned there was a great joy and celebration. Chiquita and her husband were reunited. She went back to her humble home to be reunited with her two children. Kin-kin, two and a half-year-old girl and her one-year-old son, Daryl. It was a truly joyful homecoming for she had never been away from them before. She felt weak, tired and worn out as did all her companions. But they felt that it was not for nothing. A great deal had been achieved. At least that’s how it seemed.

How long, Lord?

That was last November 1997. Still today, not one of them have put single mark on the land that President Ramos ordered would be given to them. Bureaucratic delay, legal cases and local political connections have prevented this. The farmers have had picket the offices of the Department of Agrarian Reform to get them to act on the President’s order. And now the local registry of deeds in Bukidnon refuses to admit their claims and register them as owners, citing the excuse that there is an on going Supreme Court case. Everywhere the farmers turn another legal obstacle is placed in front of them. they know that the Quisumbing have filed a case in the Supreme Court, but how long will it take? “Why?” the farmers ask. Are they not now installed on their and if they have a written order on the President himself? How can they tolerate the system that gives with one hand and allows armed thugs to keep them off their land with the other? Just when will justice be done? When will these people suffer enough?

Chiquita stands outside the land she dreams of, holding her two children close to her. “They have surrounded our land with pillars and barbed wire because Quisumbing does not want us to enter. We feel oppressed and downtrodden because we stand here outside the land which is ours, for our future and especially for the future of our children.”

As we go to press, the Supreme Court has finally ruled that the Sumilao farmers have lost their claim on the 144-hectare Quisumbing Estate. The farmers’ lawyers predict that “in the coming months, the effects of the decision would be felt by other farmers seeking to own lands”

We Lepers

By Sr. Georgina Delgado op

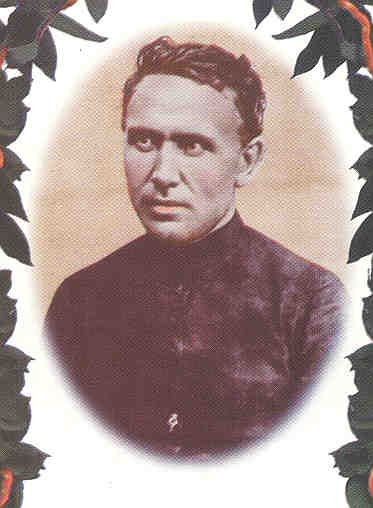

Blessed Damien De Veuster, SS.CC.

Born : January 3, 1840

Died : April 15, 1889

Feast Day : May 10

Since I first came here to Hawaii in 1982, I have been keeping this secret desire in my heart to see Father Damien’s grave and the place were he demonstrated the greatest act of love. My opportunity came when hundreds of people from other islands, the mainland and even Europe gathered in Molokai to celebrate the interment of Blessed Damien’s relics. But first let me tell you about Blessed Damien.

Damien De Veuster, a young Belgian priest, had served nine years as a missioner in the Hawaiian Islands when he felt called to request a perilous assignment. He asked his superiors that he be allowed to serve on the island of Molokai, the notorious leper colony.

Westerners had arrived in the Hawaiian Islands only late in the eighteenth century, finding a native population of about three hundred thousand. Within a hundred years the ravages of disease had reduce this number to fifty thousand. Among many illnesses, the most dreaded scourge was leprosy. The first case appeared only on 1840, but within thirty years it had reached epidemic proportions. Helpless to control its spread and unable at that time to offer any remedy, the authorities responded in 1868 by establishing a leper settlement on the remote and inaccessible island of Molokai. By law, Hawaiians found to be suffering from the disease were snatched by force from their families and communities and sent to this island exile to perish.

Conditions on the island were horrific. Patients were literally dumped in the surf and left to make their way ashore, seek shelter in caves or squalid shacks, and cling to life as best they could, beyond the pale of any civil or moral law.

It was to this island that Father Damien was assigned. Form the beginning he sought to instill in the members of his ‘parish’ a sense of self-worth and dignity. His first task was to restore dignity to death. Where previously the deceased were tossed into shallow graves to be consumed by pigs and dogs, he designed a clean and fenced-in cemetery and established a proper burial society. He constructed a church and worked alongside the people building clean new houses. Within several years of his arrival the island was transformed; no longer a way station to death, but a proud and joyful community.

As part of his effort to uplift the self-esteem of his flock, Damien realized from the beginning that he must not shrink from contact with the people.

FATHER DAMIEN OF Molokai

1840-1889

Father Damien ministered to the sick and dying lepers who were banished to the island of Molokai. The Hawaiian royalty supported him with great ‘aloha’. He was beatified in June of 1995 by Pope John Paul II.

Despite the horrid physical effects of the disease, he insisted on intimate contact with them. When he preached, he made a habit of referring to his flock not as “my brothers and sisters,” but “we lepers”.

One day this reference assumed new meaning as Damien recognized himself the unmistakable symptoms of the disease. Now he was truly one with the suffering of this people, literally confined, as they were, to the island of Molokai. Despite the advancing illness, which eventually ravaged his body, he redoubled his efforts, working tirelessly in his building projects and his pastoral responsibilities.

In his last years he suffered terrible bouts of loneliness, feeling keenly the lack of a religious community of support, and even the opportunity to receive absolution. On one occasion a visiting bishop refused to disembark from his ship. Damien rowed out to meet him and suffered the humiliation of shouting up his confession. Because of fear of contagion he was even forbidden to visit the mission headquarters of his order in Honolulu.

Damien died of leprosy on April 15, 1889. By that time his fame had spread widely throughout the world. He was beatified in 1995 by Pope John Paul II

It took this account from ALL SAINTS by Robert Ellsberg.

As I said above, I joined the group going to Blessed Damien's grave. We knew we got to the island of Molokai, we passed through rugged and dusty roads. Looking at the steep mountains and wide oceans that enclosed the peninsula of Kalaupapa put me in awe – an awe that made me reflect on Blessed Damien’s shining witness of love and care for the poorest, the most abandoned and forsaken.

As I touched blessed Damien’s relic wrapped in ‘Kapa’, I felt an inner peace, joy and strength that made me shed some tears. It seemed that Blessed Damien’s spirit penetrated my soul. The words from the song Heal the World rang in my ears. It was as if Blessed Damien was saying these works to me there’s a place in your heart and I know that it is love... in this place know that it is love... in this place you’ feel there’s no hurt or sorrow. Heal the World, make it a better place for you and for me.

By law, Hawaiians found to be suffering from the disease were snatched by force from their families and communities and sent to this island exile to perish.