A Land Of Blood And Poison

By Hugh O’Shaughnessy

Since we have Filipino missionaries in Colombia, this should be of interest to the readers. Apart from that, it is interesting that in Colombia the beleaguered peasants have started Peace Zones as we did in the Philippines in the nineties. Colombia is a very large country. There are areas of the land which are mercifully free from the turmoil we describe here. (Ed.)

Scores of Oscar Romeros, martyrs for their faith, for peace and for their fellow men and women, are going to their deaths every year in Colombia. Lay and clerical they die, as people are sucked into a swamp of mud and blood, war, poison and deceit which has no present parallel in the Western Hemisphere and few, if any, parallels in any other parts of the world. The killing has been going on for half a century, well before Colombia was a source of drugs. In the decade after the killing of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a popular Liberal leader, in 1948, more Colombians died in battles between Liberals and Conservatives than Britain lost in the Second World War. The killing continues.

Easy choice: peace

Here are some examples. In 1996 the people of San José de Apartadó in the wooded hills above the plain of Urabá, where mile after mile of banana plants grow and which had become the most violent country, decided they wanted to opt for peace. The village itself had been founded a few decades previously by a group of displaced people, but now the villagers wanted to opt out of the violence which had pitted the army and its allies in the paramilitary death squads against the supposedly left-wing guerrillas; and the plantation bosses against the workers who were bold enough to join a trade union.

What it takes to put down arms

San José therefore proclaimed itself a “peace community”, the villagers pledging themselves not to bear arms and asking what are commonly known in Colombia as “armed actors” not to bring arms into the village. Their action attracted the support of many inside and outside Colombia. A wall in the little square in the village bears the message of support from Jeremy Thorp, the British ambassador, and a plaque commemorates a gift from the Dutch government. For several years at least two members of the Peace Brigades International (PBI) have been constantly in the village. The PBI are made up of foreign, mostly young, volunteers who live in areas of conflict and by their very presence seek to deter the sort of bloodletting which might be carried out by those who were sure their actions would never be observed and reported on outside the country. Infuriated and undeterred, the soldiers, paramilitaries and guerrillas have killed about 80 of the 1,000 villagers since the community was established. Under the protection of the army, the death squads routinely rob the villagers of the money from the sales of their cocoa and bananas as it is sent down the track to the bank in the nearest town. The last incursion was in March when a group of masked men, including at least one soldier from t he Colombian XVII Brigade, burst into San José after dark, burning and looting and warning the inhabitants to get out forthwith.

The survivors remain nevertheless, despairing, but for the moment determined that their idea shall not die. They tend the little memorial to their dead at the foot of the wall bearing Mr. Thorp’s words.

Padre Eusebio

At the other end of the country, on the River Putumayo, a priest whom I shall call Padre Eusebio goes about his business in the recently established Diocese of Sibundoy-Mocoa. Though he has happily stood in at the local army base when its regular chaplain has been absent, he is known to be opposed to the situation where the army and their death squad allies, armed by the United States and trained by US troops and mercenaries paid by the authorities in Washington, terrorize the neighborhood.

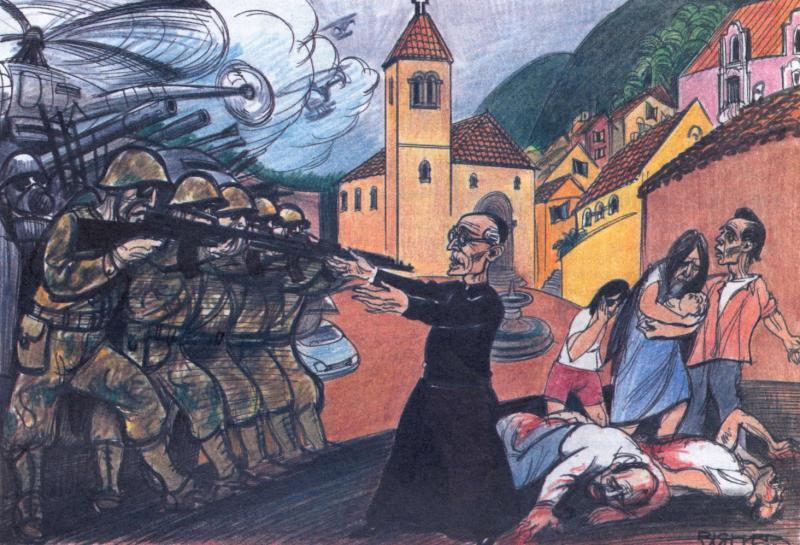

Mass over piled guns

A few months ago Eusebio, this known critic of the situation of conflict, found a whole new congregation at a Sunday Mass in one of the parishes he serves. The regulars had been displaced in the church by a battalion of troops in uniform who were all carrying their arms. The challenge and the threat to what the Colombian army and its US allies looked on as a turbulent priest could not have been plainer. So Eusebio addressed his newly assembled congregation and told them that Mass would not proceed unless the forest of guns were first piled up outside. Officers were seen to be talking urgently on their radios, presumably with their superiors at the base. In five minutes the weapons were stacked outside and the Eucharist went ahead.

Eusebio won his point that Sunday, though the army and its foreign backers made it clear that they would have happily done to him what the late Colonel Roberto d’ Aubuisson and the same foreign backers had done to Archbishop Romero as he said Mass that day in March 1980 at the hospital chapel in San Salvador.

Plan Colombia

The Plan Colombia continues, with aerial fumigation bringing severe skin rashes and respiratory and digestive illnesses to children and adults, who are pelted with the toxins which also destroy food crops and poison the land and water on the slopes of the Amazonian basin. In an ugly resonance from the past, some of the fumigation aircraft are operated by a US company which was contracted to deliver narcotics for the Contra terrorists in Central America during the Reagan onslaught against the government of Nicaragua. Despite the Plan, the coca bushes still flourish.

The death squads have taken over the town of Barrancabermeja, Colombia’s oil capital, this year. “We’ve lost count of the number of murders,” says one human rights worker. “We just fish the corpses out of the river.”

Displaced souls

In the capital Bogotá itself, human rights workers go in fear of their lives. An aid agency with counts the rise in displacement and exilings has prudently donated doors of bulletproof glass to the group which charts the fate of Colombian displaced people. Those in authority do not like to be reminded that 2.1 million people are displaced in their own country and perhaps 4 million have sought refuge abroad. Romeros and potential Romeros are to be found in many trades and professions, notably the law, the media, the trade unions and politics.

It is extremely difficult to give a concise overview of the tragedy of Colombia in 2001. The most illustrative facts are to do with violence. The government says there were 25,600 murders in 2000, an average of 70.1 every day, while kidnappings last year were a veraging 8.3 a day.

Concealed atrociti

The outside world’s view of the horror of life in Colombia has been colored by myth-making by all sides while powerful forces at every point on the political spectrum are at work using every art of lie, euphemism and obfuscation to hide the raw truth.

Drug Peddlers

The particular concerns of recent US governments – that narcotics be destroyed abroad and anti-drug action within the US itself be limited to the imprisonment of minor drug peddlers, often from the racial minorities, while the major drug distributors work on in undisturbed – have perverse results. Non-Colombians are often under the delusion that narcotics are the principal problem in Colombia and that the guerrillas – christened “narco-guerrilas” by one US ambassador – are the source of the country’s woes. The fact that earlier this year the representative in Bogota of the UN Drug Control Programme declared that the paramilitary death squads, allies of the armed forces, were closer to drug trafficking than the guerrillas has not been widely registered. Nor is it well known that Colonel Hyett, a US military attaché in Bogotá, and his wife were themselves found guilty of narcotics offences.

Deaths of journalists

The veil of ignorance is thickly woven. Twelve Colombian journalists have so far been killed this year and authors are routinely murdered or forced into exile. Foreign journalists, though less at risk of their lives than the locals, have much to battle against. Colombian politics, apparently split neatly between a Conservative and a Liberal Party, are in reality very complicated and vary wildly from one part of the country to another. Voter abstention at election time has reached very high levels.

Endless war

Things will surely get worse before they get better. New weapons are beginning to pour into the country under Plan Colombia, raising even higher the level of violence. The death squads are organizing themselves with increased political sophistication and claiming seats at any negotiating table where government and guerrilla forces gather. The Pastrana government, which promised peace, has been blown onto a war course by the Plan Colombia.

As the murder continues there are few enough bases for hope. Paradoxically perhaps, the only substantial one is the doubt surrounding Plan Colombia itself. It is looked on as poison by the European Union. It has been criticized lately by Henry Kissinger and the Rand Corporation, a conservative US think tank. Some of the US military are also fearful of it as a recipe for the eventual embroilment of their country in a South American Vietnam, a worry that is behind the decision to try to fight the war in Colombia with US-funded mercenaries rather than with US regular troops.

While Plan Colombia and the further militarization of the country survive, however, war clouds will continue to hang over Colombia.

Salamat sa The Tablet